When I taste wines for our database of 40,000+ tasting notes on this site, I always give a score and a suggested drinking period. I give the score somewhat reluctantly as I really don’t think something as exciting as wine can be reduced to a number. I give the suggested drinking dates fully aware of the difficulties of prediction but with no hesitation, as I think this constitutes some of the most useful advice of all from the point of view of those who spend any of their hard-earned cash on fine wines.

A typical drinking bracket would be ‘Drink 2010-11’ for simple young whites, ‘Drink 2015-25’ for the sort of complex reds that might be on the market today. But yesterday, for the first time ever, I found myself writing 'Drink 1920-2020' – for several wines. And the wines were dry whites, all made from the Riesling grape in the Rheingau – the likes of 1901 Hattenheimer Speich Cabinet, 1899 Hochheimer kleines Rauchloch Cabinet and 1898 Kiedricher Gräfenberg Cabinet, all from the cellars of Kloster Eberbach, the recently revitalised wine domaine of the hauntingly quiet Cistercian abbey in the wooded hills above the Rhine in the Rheingau.

As members of my Purple pages know, I am horribly stingy with my scores. An 18-pointer is something very special, but in one flight alone yesterday, of ancient dark Trockenbeerenauslesen, I found myself awarding three 19.5s in a single flight! And one of my 20-20 wines carries the name of a vineyard that no longer exists as a separate entity.

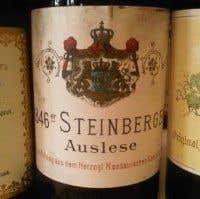

Monday and Tuesday’s two-day tasting of Rieslings from 100 different vintages from the unusually well-stocked cellars of the Kloster Eberbach truly was an exceptional experience. Especially when one considers that the oldest wine, an 1846, was not dead. (It smelt of Laphroaig malt whisky, but it was alive.)

Everyone knows that TBAs are famously long-lived, but perhaps the most exciting thing for me was the overwhelming proof that fine dry Riesling really can last for more than a century. These Cabinet wines were admittedly called so because they were regarded as the finest wines produced at Kloster Eberbach in that vintage. But here was the clear demonstration that a century ago, the finest Rheingau Rieslings were dry – in fact have a remarkably similar constitution to the new Erstes Gewächs dry Rieslings currently being made in the Rheingau, and the wines called Grosses Gewächs elsewhere.

British and American importers of German wines, kindly take note. And, as I have always said, remember that Riesling is the finest white wine grape in the world. (Some people screw it up, but that’s not Riesling’s fault.)

I will, of course, be publishing the full story, and tasting notes, on my Purple pages.