This article was also published in the Financial Times.

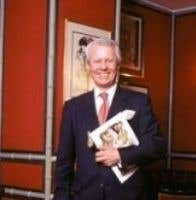

Silvano Giraldin has finally hung up his order pad and pen. After 37 years initially alongside Albert Roux and then his son Michel, Giraldin, who has been General Manager and Director of Le Gavroche in Mayfair, London’s most respected French restaurant since 1986, is retiring. This warm, welcoming Italian has seated his last guest; proffered his last glass of champagne; taken his final order for the Gavroche’s signature soufflé suissesse; and will no longer be on hand to wish his guests bon appétit or good night.

With his departure goes a significant slice of London restaurant history during which Giraldin has been as highly regarded by his customers as he has been by his fellow restaurateurs and chefs. One described quite how pleasurable it had been to work alongside Giraldin in the Academy of Culinary Arts, a professional training organisation, adding, “The remarkable thing about Silvano is that professionally he is so demanding but personally he is so unassuming.”

Just before his farewell, I collected Giraldin from Le Gavroche at 2pm to whisk him off to nearby Locanda Locatelli for the late lunch that is the restaurateur’s norm. My initial question as to how good business currently was produced not only his trademark toothy smile but also a feisty response.

“I have to say it’s fantastic. I thought that this year was going to be difficult so I only budgeted for a two per cent increase in sales. But so far we are over five per cent up on last year and we are full all the time. What I cannot understand though is why the competition is making life so easy for us.”

Without drawing breath, Giraldin explained. “There have been three new big French restaurant openings this year in central London – Alain Ducasse at The Dorchester, Hélène Darroze in The Connaught and Ambassade de l’Ile in South Kensington – and they have all opened at such high prices that they make us look very reasonable. These chefs may have great reputations in France, but other than to a small number of people who are really keen on their food, they are hardly well known here. You can’t start flashy and with high prices like this in London. You have to be humble and to build your clientele gradually. I went to one of these restaurants for my birthday dinner and my bill came to over 750 pounds for the four of us. It’s too much. But it’s great for us.”

Giraldin’s current bonhomie hides some deep-seated scars however. A mainstay of Le Gavroche’s popularity is its great-value lunch menu, 48 pounds for three courses including half a bottle of wine and mineral water per person, coffee and petits fours, a formula Giraldin explained he was forced to introduce during the recession of the early 1990’s. “When the first Gulf War started our customers vanished and this was our response although the price was 35 pounds then. But what I cannot understand is why, although many others offer some form of prix-fixe lunch menu, they still add supplements for certain dishes or don’t include the coffee which isn’t the most expensive ingredient. I think there should be an inclusive set menu or there is no point in offering one.”

While this approach revived business it had one unforeseen consequence, the demotion of Le Gavroche from three Michelin stars to two in 1992. There was no option, Giraldin continued, other than to cut staffing levels and this was the guide’s response (although staffing levels have long since been restored – the restaurant employs 50:50 split equally between the kitchen and the restaurant). “I don’t regret this decision for one moment, although I firmly believe Michel’s cooking deserves the very highest accolades, because this commercial approach has allowed us to remain independent. I would much rather we were full with two stars than less than full with three.”

The manner in which this lunchtime menu is written was also a response to changing times. Mayfair has long been home to numerous American and Arab companies that have been unwilling to sanction alcohol as part of any lunchtime entertaining. The all-inclusive price circumvents this obstacle to the satisfaction of corporate accounts departments.

As he viewed with obvious pleasure the manner in which his plate of spaghetti with lobster was placed before him, Giraldin touched on other changes he had seen. The decision in 2000 to allow in men without ties, although jackets are still compulsory; the emergence of more and more women as hosts which means that handing the priced menu to the appropriate person has to be handled more sensitively; and the fact that, as a result of our changing work patterns, Giraldin manages to go home an hour earlier than he used to.

“When the City finished at 6pm and when crossing London was easier and there were fewer restaurants, our first bookings were often not until 8pm but then we would still be busy at midnight with customers from the theatre or the opera. Now far more people want to come at 7.30pm and to meet their partners here directly from the office. The way in which our customers use the restaurant has changed but I hope our principles have not.”

When I asked him what had excited him most about his role, Giraldin’s response was surprisingly brief. “Details,” he replied, but then he continued, “Over the years I may have been too hard on my staff but I am convinced that I can make anyone a good waiter as long as they have the right attitude. The key to doing their job properly is that they must always be in a position to prevent a customer from asking for anything. How they approach a table is critically important and they must never, ever start a conversation or interrupt. The best service is always conducted through eye contact with the waiter always on the lookout. I know when I walk into a restaurant and see customers looking around trying to catch a waiter’s attention that the service is not going to be good.”

This style, together with the recognition that a waiter is an actor who has to put on a good performance, have been Giraldin’s hallmarks, but he remains doubtful about how best this knowledge can be passed on. “For a chef, it’s quite easy. Their recipes can be copied and their dishes photographed and sent round the world. The principles of good service cannot be replicated so easily.”

He is confident that his anointed successor, Emmanuel Landré, who at 32 has spent the last 10 years at Le Gavroche, will replicate his skills and little will change in a restaurant that recently celebrated its 40th birthday. Giraldin will concentrate on passing on his knowledge, independently and alongside Albert Roux, while still overlooking the restaurant’s wine list and their regular wine dinners.

As we were about to leave we were joined by chef Giorgio Locatelli. They promptly slipped into their native Italian and Locatelli assured him that this particular table would always his and that he hoped to see much more of him now that Giraldin was no longer working lunch and dinner. A sentiment many London chefs and restaurateurs would echo.

Le Gavroche, 43 Upper Brook Street, London W1, 020 7408 0881, www.le-gavroche.co.uk