Northern Rhône

It's not difficult to see why vine-growing is relatively uncommon on the steep, wooded banks of the Rhône south of Lyons. These vineyards, probably the oldest in France, have had to be etched into the mountainside on narrow terraces (not unlike port country in the Douro) and at dizzying gradients. Some are so steep that pulley systems have to be used for grapes and equipment as in Switzerland. This, furthermore, is countryside that has now been fully invaded by industry and is well-adapted to other, easier crops such as fruit trees on the plateaux above the river. To grow vines in the northern Rhône's only commercially viable sites, the ones that catch the sun for long enough to ripen grapes fully, you have either to inherit an established vineyard (usually on the right bank) or to be sure of fetching a high price for the resulting wine.

The great majority of wine made here is made from the Syrah grape, and the region's most famous wines are the deep-flavoured, long-lived reds Hermitage and the theoretically more fragrant and delicate Côte Rôtie.

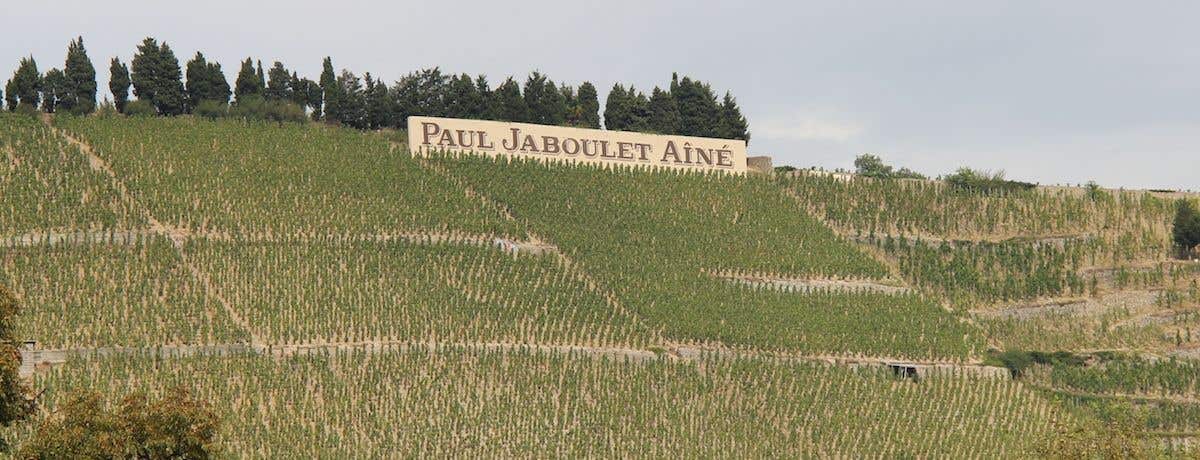

The most famous producers of the northern Rhône are family enterprises which vinify their own grapes but also buy in grapes and wine the length of the entire Rhône valley. The three biggest are Marcel Guigal of Côte Rôtie, whose single vineyard wines are sought after worldwide; Michel Chapoutier who practises biodynamic viticulture; and, another Hermitage specialist, Paul Jaboulet Aîné, sold by the Jaboulet family to the Frey family of Ch La Lagune in Bordeaux in 2005 .They each have their own vineyards but buy in extensively from the hundreds of smallholders who still cultivate these physically demanding vineyards. As elsewhere, an increasing number of these smallholders are now bottling their own wine and their challenge, along with that of an increasing number of ambitious newcomers to the region, has done nothing but good for the overall quality of Rhône wine.

Côte Rôtie is in fact not just one but a series of 'roasted slopes' folded above the little town of Ampuis. Only those facing south or south east on the schists of this right bank of the river are worth the extreme discomfort of cultivating them and, especially, picking their produce. Those to the south are collectively known as the Côte Blonde and the wines they produce supposedly mature rather earlier than those produced on the Côte Brune to the north, although traditionally the wines from these areas have been blended. (There are vineyards on the flatter land above these slopes but they are entitled only to the generic Côtes du Rhône appellation, which very much more commonly applies to wines made in the southern Rhône.)

One man has made a name for himself and indeed the whole appellation by flying in the face of Côte Rôtie convention. Marcel Guigal's special bottlings of La Mouline, La Landonne and La Turque, the so-called 'La-La wines', have become some of the most sought-after bottles in the world, thanks to their low yields and uniquely long maturation in new oak, which make them massively appealing in youth as well as promising an exciting old age. Guigal makes a fourth special bottling of Côte Rôtie above his regular bottling labelled Brune et Blonde named after the manor of his native town, the grand Château d'Ampuis, which he now owns.

Côte Rôtie is stereotypically distinguished from Hermitage by its perfume, which is in some cases due to the inclusion of a small proportion of white Viognier grapes (the same as those grown in the neighbouring appellation of Condrieu), but in practice most Côte Rôtie is 100 per cent Syrah. The appellation's vines are trained to help withstand the twin local dangers of wind damage and soil erosion, with pairs of vines staked to meet in a point, making the roasted slopes look as though they are covered in Christmas trees. Some other reliable producers of Côte Rôtie are Gilles Barge, Bernard Burgaud, Clusel-Roch, Levet, Jamet, Ogier, Rostaing, Jean-Michel Stéphan and Vidal-Fleury (the merchant house for which Marcel Guigal's father once worked as cellarmaster but which now belongs to Guigal).

The amount of Viognier grown in the northern Rhône is relatively tiny, and the peachy, full-bodied Condrieu it produces could generally be sold three times over by growers such as Yves Cuilleron, Pierre Gaillard, Georges Vernay and François Villard, so fashionable has this wine style become. The merchants try to buy as many Condrieu grapes as possible. Guigal's single-vineyard Doriane is setting a new standard, while Delas has a long history of getting Condrieu right. Château-Grillet, acquired in 2011 by French billionaire and owner of Ch Latour François Pinault, is a 3.8 ha (9.4 acre) single-property appellation slightly downriver of Condrieu whose wines are even more dramatically priced.

Hermitage is produced 50 km (30 miles) downriver on a bald suntrap of a hill on the left bank above the narrow town of Tain, or rather Tain l'Hermitage as it has become known thanks to the fame of Hermitage's densely strapping wines. There was a period in French wine trade history when it was common practice to order red wines that had been hermitagé, or had had Hermitage added to them for colour and strength. White Hermitage is also made, from Marsanne and Roussanne grapes. It is unusually full-bodied and can be difficult to appreciate until its bouquet has developed after many years in bottle. Sweet vin de paille, made from dried grapes, is a speciality.

In and around Tain and its sister town Tournon, just across a rickety footbridge over the Rhône, are a bevy of gifted and determined winemakers, not just the large merchant houses of Chapoutier, Paul Jaboulet and Delas but much smaller family domaines such as superstar Jean-Louis Chave. The co-operative Cave de Tain l'Hermitage is also admirably aware of quality.

Most of these producers also make Crozes-Hermitage, the area's much, much bigger, less demanding red and white wine appellation on the flatter land around the hill of Hermitage. Red Crozes from one of the area's best merchants or one of the more gifted producers such as Belle, Domaine du Colombier, Graillot, Pochon or Domaine Marc Sorrel are the northern Rhône's great wine bargains.

While Crozes-Hermitage regularly represents more than half of all the wine produced in the northern Rhône, St-Joseph (another red and white appellation made from Syrah and Marsanne/Roussanne respectively) can often represent almost one bottle in four. The appellation was, often unwisely, expanded dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s and straggles down the right bank of the river from Condrieu almost as far south as St-Péray. There can be a dramatic difference in concentration and quality between the wines made on difficult terraces just above Tournon and those which gush forth from the much flatter land. It's worth paying St-Joseph's price premium above Crozes only for the likes of Jean-Louis Chave, Yves Cuilleron, Émile Florentin, Bernard Gripa, Jean-Louis Grippat (owned by Guigal), Jean Marsanne and André Perret.

Even though the northern Rhône has benefited from an enormous amount of attention in recent years, Cornas is still an underappreciated appellation producing very worthy and eventually exciting Syrah reds. They do demand ageing though, which is presumably what makes them less attractive to modern wine drinkers. Auguste Clape is the local hero, with Jean-Luc Colombo, Durand, Robert Michel, Domaine du Tunnel's Stéphane Michel and Vincent Paris also highly regarded.

The curiosity of the northern Rhône is St-Péray, both still and sparkling white made from Marsanne and Roussanne grapes of increasing quality.