This is a longer version of an article published by the Financial Times. See Current champagne vintages for my detailed tasting notes.

It has long struck me as rather strange that one of the most expensive wines we buy has so routinely been sold with less information on how old it is and what’s in it than a can of baked beans. At least a baked beans label gives us some clue about ingredients and a suggested ‘consume by’ date. But a typical bottle of non-vintage champagne is sold without any such guidance. By law all wine bottles have to be stamped with little lot numbers that can be decoded by the brand owner and the bottler, but they mean nothing to us consumers. For all you know that £37 bottle of Mumm sitting under bright lights on the shelf at your local convenience store has been there for so long that the wine long since lost its sparkle.

With still wine, most of which is vintage dated, we know at a glance how old it is. And since most of it carries a front and, increasingly, a back label, we are usually told quite a bit about what is in the bottle. An official appellation is enough to give well-educated wine lovers many a clue about geographical provenance. Grape varieties are in many cases cited if not on the front label then on the back. Indeed there has been a heartening increase in the amount of information aimed at wine geeks like me that is spelt out on back labels.

But we are left in the dark about far too many champagnes and sparkling wines – particularly those without a vintage date on them (which constitute more than 98% of all champagne produced). Non-vintage champagne is typically made of a blend of the most recent vintage together with a much smaller proportion of some older wines. It may be any combination of the main three permitted grape varieties Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. And those grapes may come from any of hundreds of villages. In an ideal world, I’d appreciate some information about all these ingredients.

But in particular I’d love to know when the blend was created (which would indicate which is the main vintage in it – the year before). This is sometimes described as the date of tirage, when the bottles containing the new blend, together with extra yeast designed to provoke a second fermentation in bottle that will give off carbon dioxide, are laid in the cellar.

But, even more importantly, I’d like to have some idea of how long the bottle has been in commercial circulation, not just for the sake of freshness but because champagne ages differently before and after the vital process of disgorgement when the dead yeast cells are expelled from the bottle and the wine is topped up, generally with a mixture of wine and a little sweetness known as the dosage. (If no sweetness is added, the champagne is described as Zero Dosage or Brut Nature.)

The longer a champagne ages (in ideal conditions) after disgorgement, the toastier and richer the wine tastes whereas champagnes tend to taste zippier and more austere immediately after disgorgement.

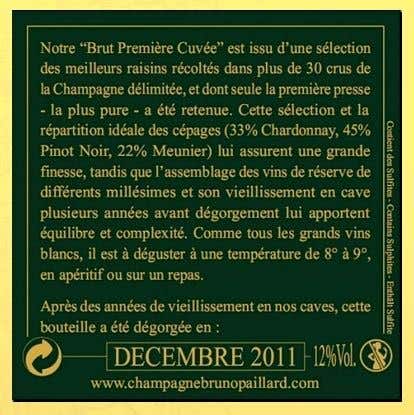

The big clue here would be the date of disgorgement and, to his great credit, champagne innovator Bruno Paillard of the eponymous champagne house has been citing disgorgement dates on the back labels of all his champagnes since 1983 (example above). Most other champagne houses, with the exception of Philipponnat, who followed Paillard 15 years later, have dragged their feet for decades over this issue. But so convinced is Paillard of the importance of disgorgement dates that he sells the same wine disgorged at different times to demonstrate how different they are.

There is a particular problem for wine commentators here. When we review a non-vintage champagne with no dates on the back label, we have no way of identifying the particular bottling we tasted – and nor do our readers – which is not at all helpful when new bottlings are created at least once a year and there can easily be two or three in commercial circulation at any one time.

For many years the popular defence was that the purpose of champagne blenders was to smooth the differences between non-vintage bottlings and that therefore there is no difference between them. But this argument was dealt a body blow in 2012 when Krug, the luxury champagne house in the most important family of champagnes of all, those belonging to the LVMH group, decreed that they would henceforth be printing a code on the back of all labels of their ‘multi vintage’ (nothing as common as non-vintage for Krug) Grande Cuvée that would disclose, via smartphone or website, the complete history of each bottling.

Last month was the champagne producers’ annual display of their wares to the British wine trade. I went along to taste and concentrate on the vintage-dated wines on the basis that these at least are uniquely identifiable bottlings that I could recommend, or not. I was able to taste 49 wines from nine different current vintages, of which 2008 was the most common, and was pleased to see that Ayala, Beaumont des Crayères, Besserat de Bellefon, Bollinger, Paul Déthune, Charles Heidsieck, Lanson, Henri Mandois, Moutard, Sanger, Veuve Fourny, and of course Bruno Paillard and Philipponnat, all disclosed the disgorgement dates on their back labels, and André Jacquart had a panel clearly designed to show this important bit of information but the bottle I saw didn’t happen to have it printed. So almost one quarter of the champagne houses represented, generally but not exclusively the bigger houses, now acknowledge that the date of disgorgement is sufficiently important to be worth communicating to their customers, on vintage-dated champagnes anyway.

I have found over the last few years that the new wave of top-quality champagne growers – the crème de la crème of the nearly 2,000 growers who make their own champagne (as opposed to the more than 2,500 who sell their grapes to the local co-op) – are particularly good at disclosing information about what they have to sell. It is by no means uncommon to be able to read exact proportions of each grape variety, each vintage, dosage (or residual sugar) in g/l, and some indication of geographical provenance on the back labels of the small-scale likes of Bérèche, Ulysse Collin, Diebolt-Vallois, and Egly-Ouriet (this example at least tells you the wine is unfiltered, spent 48 months on the lees and was disgorged in July 2013).

Things are definitely moving in the right direction.

RECOMMENDED VINTAGE CHAMPAGNES

Billecart Salmon, Cuvée Nicolas François Billecart 2002

Bollinger, La Grande Année 2005

Paul Déthune, Grand Cru 2005

Deutz 2007

Duval-Leroy, Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru 2006

Pierre Gimonnet, Gastronome Blanc de Blancs 2008

Gosset, Grand Millésime 2004

Alfred Gratien 2000

Charles Heidsieck 2005

André Jacquart, Le Mesnil Expérience Blanc de Blancs Brut Nature Grand Cru 2007

Cave Co-opérative Le Mesnil, Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru 2007

Bruno Paillard, Blanc de Blancs 2004

Philipponnat, Blanc de Noirs 2008

Louis Roederer 2008

Pol Roger 2004

Veuve Fourny, Blanc de Blancs Premier Cru 2008

For detailed tasting notes, see Current champagne vintages.