21 March 2023 Malu Lambert reports on how Chenin Blanc is lighting the way for wine-language inclusivity in South Africa.

Tinashe Nyamudoka paints a vivid picture of his Zimbabwean childhood. As he talks you can smell the grassy, alpine air of the lush mountains he hiked with his grandfather. You can taste the red-berried tang of the fruit he calls ‘nhunguru’ and ‘nhengeni’ (wild plum and berries). He’s gifted at describing scents and sights. Yet he says that when he was working in Cape Town restaurants, he found himself struggling to describe wines, as the common descriptors were unfamiliar. ‘It was something I had to learn.’

As in most wine regions outside of Europe, wine language in South Africa is imported. Many of the traditional descriptors used in educational materials, tasting notes and so on are a verbal hangover of colonialism. The term gooseberry, for example, is confusing to most South Africans. The local version isn’t the tart, green English one commonly used as a Sauvignon Blanc descriptor; the Cape gooseberry is orange, with sweet flesh.

In a republic such as South Africa, with 11 official languages, a Eurocentric wine vocabulary excludes most of the population. It’s also simply not good business. Why disregard large demographics of potential wine drinkers – especially as trends show a global decline in wine consumption as oenophiles start to age out?

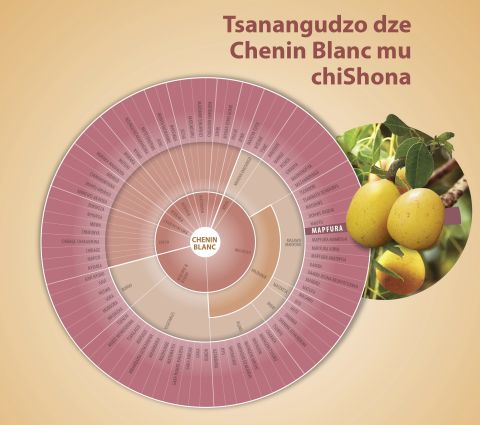

So when Nyamudoka launched his wine brand Kumusha (the Shona word for ‘your home’ or ‘your origin’), he looked closer to home for tasting-note descriptors. He references things such as tsvubvu, a small black berry, to describe the fruit flavour in the Kumusha Cabernet Sauvignon, and blackjack leaf, which is to his palate what blackcurrant leaf is to a European one, while matunduru he says is similar to peach and apricot.

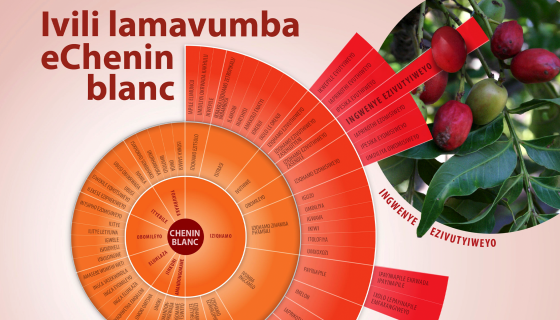

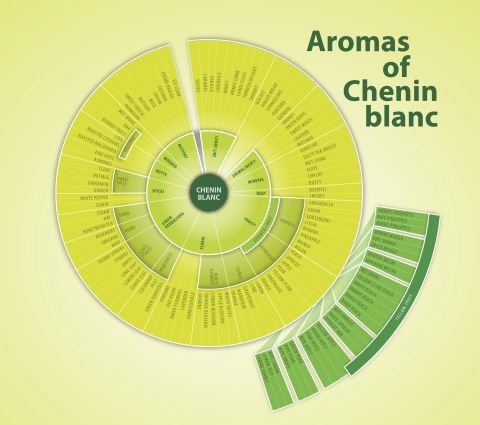

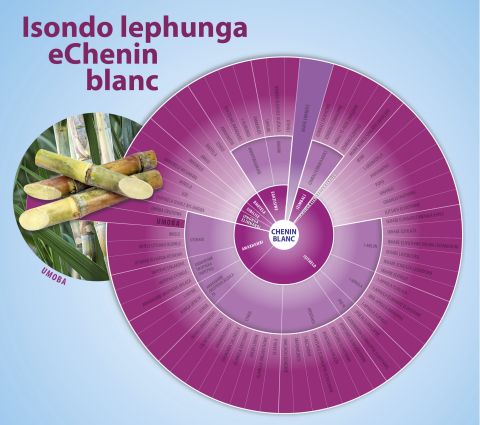

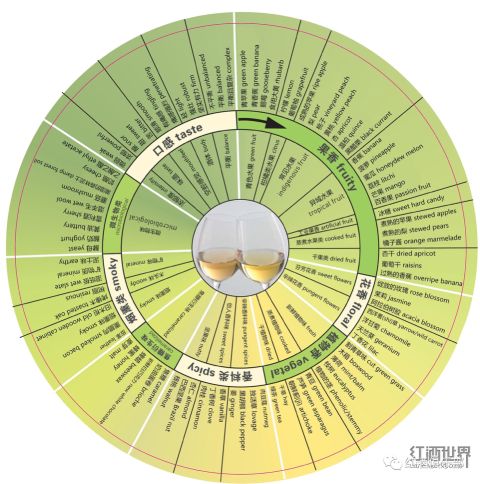

Now South Africa’s Chenin Blanc Association (CBA) is launching its own initiative under the direction of project leader Nolene Nel and manager Ina Smith. South Africa produces the most Chenin Blanc in the world, and over the last two decades the variety has become something of a critic’s darling. To widen the variety’s appeal, the association has created a Chenin Blanc aroma wheel with translations into Xhosa, Zulu and Shona. (Shona, while not an official language of South Africa, was chosen for the country’s large Zimbabwean population and its devoted contingent of wine stewards and sommeliers.) The task was more than a simple translation job, says Christina Harvett of the CBA. ‘It was more of a process of finding the essence of Chenin Blanc through cultural specific reflections.’

Reinventing the wheel

The original Chenin Blanc aroma wheel was developed in 2005, and updated in 2016 using tasting data compiled by Dr Hélène Nieuwoudt, a senior researcher in wine biotechnology at Stellenbosch University.

This latest project takes a novel tack. ‘For many years we have taught people what they should taste and perceive in wine’, remarked Dr Nieuwoudt during a presentation at the Chenin Blanc International Congress 2022. ‘However instead of us saying to the consumer “let’s educate you”, with this [translation project] we’re rather saying you can educate us.

‘Our population is richly diverse and we want Chenin Blanc to be inclusive of that. I myself have never seen an elderflower’, she said, laughing. ‘The time for dictating what people smell is over.’

The three wheels were compiled through a series of workshops in 2022. The wines were selected at earlier tastings to zero in on six wines that had as many of the characteristic properties as possible within the dry Chenin styles.

Three separate tasting panels of Shona, isiZulu and isiXhosa wine lovers were tasked with tasting these wines and describing them in their mother tongues using indigenous taste references. The discussions resulted in descriptors in each language independent from the English wheel. Dr Jeanne Brand, a sensory scientist at Stellenbosch University, interpreted the resultant data. ‘We thought we were going to cross language barriers, but it turned out to be much more than that. It became a continuum of cultures learning from each other.’

Nyamudoka, who was the chair of the Zimbabwean tasting panel, says that not only will the wheels ‘help people like me as it broadens the conversation; it was also just a wonderful experience talking about wine in our vernacular and reliving childhood memories.’

Sommelier Eric Botha led the isiXhosa panel. He likewise relished the opportunity to talk about flavours his community is familiar with. ‘Like the scent of bread baking on the braai; fresh cow dung in the morning; the smell of rain on clay soil …’ (The isiXhosa wheel is pictured at top of this article.)

Nkulu Mkhwanazi, chair of the isiZulu group, found the experience to be emotional. ‘Chenin takes me back to my childhood in the Umlazi Township, south of Durban’, reflected Mkhwanazi. ‘All the fruits we used to eat – mangoes, oranges, peaches, pawpaws – can be found in abundance in Chenin Blanc.’

Some references came up in all language groups. Pap, a traditional maize porridge, was commonly used to describe the yeasty aroma from lees contact. Many kinds of native grains that have no European equivalent also came up.

On the Shona panel, sommelier Joseph Dhafana sees the project as an opportunity to expand into other African markets. ‘One up for diversity’, he enthused. ‘This is going to change the narrative and help wine become less intimidating to many.’

In fact, more ‘translation’ wheels are being planned for Chenin: for old-vine and sweet styles of the grape as well as projects aimed at Asia. Also on the cards is a course for wine stewards, which will empower them to talk about wine in terminology that’s truer to them.

A new wine lexicon for all?

It’s not just in the Cape that wine language is stretching. Something of a groundswell is happening across the globe with the ‘decolonise wine’ conversation heating up. Wine writer Meg Maker of Terroir Review recently led a panel discussion at the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium in Sacramento, California. The talk, ‘A new lexicon for wine’, uncovered how these established lexicons alienate newer, younger and non-white audiences.

‘There are firm commercial reasons for broadening the appeal of wine’, said Maker. ‘The only segment of growth in wine in the US is people over the age of 60, and they’re a shrinking demographic. Though it’s not as much about the commercial impact as it is about the cultural, of shifting our reference frame so that wine is welcoming, personal and creative.’

Ahead of the curve, Jeannie Cho Lee MW put forward a compelling argument for an Asian wine-tasting lexicon in her 2011 book Mastering Wine for the Asian Palate. ‘The book came together from teaching Asian students with whom I could exchange and develop a common language’, she explained. In the book she pairs grape varieties with Asian descriptors such as red dates, persimmons and gingko nuts.

‘There’s also a feeling of being seen when a tasting note resonates with you’, says Mailynh Phan, CEO of the Vietnamese-owned RD Winery in Napa. ‘Hai Tran, a sommelier, uses Maggi Seasoning sauce to describe umami in wine. We grew up with it in Vietnamese culture. To have it correlated with wine felt like I was being seen.’ The effect is profound, she says: ‘Seeing flavours that resonate in a deep way can change that thought of “wine is not for me” to “wine is for me”.’

In February this year, neuroscientist Dr Gabriel Lepousez was in Cape Town presenting a talk on the link between memory and scent. ‘The name of an odour always corresponds to the name of the familiar object of our environment. There is no abstract word in olfaction’, said Dr Lepousez. To illustrate this point, he recalled a tasting in Hong Kong in which guests noted pyrazines in a wine. The Europeans in the room described it as ‘green pepper’ and found it off-putting, while the locals compared it to ginseng root, a positive association.

Such is the power of memory and scents, he explained. ‘The sense of smell activates both the memory and the emotional centres in the brain. Smells trigger emotions, which are related to powerful and persistent memories.’

For Nyamudoka, who realised this early on, the act of simply raising a glass of wine has the power to transport him to the mountains of Zimbabwe, walking side by side with his grandfather.

Decolonising wine language is a way to open the door wider. To invite the world in. By encouraging more inclusive terminology we invite people from all cultures to relate to wine with associations drawn from their own cache of memories. After all, this is what wine is about: we sit at a table, we uncork a bottle, we swap stories and create new memories. Wine brings people together.