The UK wine trade is getting seriously interested in a group of wines they have not yet got a satisfactory name for. The working title is Lower, or perhaps Reduced, Alcohol Wines – an amorphous group of wines that are less potent than average, but these are not legal terms. And nor are they ones likely to appeal to the many British wine drinkers, men as well as women apparently, currently telling researchers and retailers that they are looking for wines that are more refreshing, simpler and fruitier. Research commissioned by UK importer PLB suggests they prefer the positive qualities of the expression ‘lighter’ to the prissy ‘lower alcohol’, and some think that the current popularity of rosé and Pinot Grigio is evidence of a trend away from high alcohol and, possibly, oakiness. ('Low alcohol', incidentally, is a legal term in the UK for a liquid under 1.2%. See more discussion of this in the introduction to my tasting notes on Lower-alcohol wines.)

Thus it was I found myself last week at a wine trade forum held in London to discuss this phenomenon, and of course how to benefit from it. American winemaker David Stevens, a partner in a company specialising in producing reduced-alcohol wines, flew over specially to take us all through the ways in which the alcohol levels in wines can be reduced. The simplest, adding water, is illegal, except in the US, although he described simple dilution as ‘probably the most common method and the least commonly admitted to’. Winemakers everywhere know that they can quite legitimately use copious quantities of water to clean tanks, pipes and so on, and that most chemical additions to wine have to be diluted, providing yet another opportunity to bring down the overall alcohol content of a wine.

But now that so many grapes are being picked at much higher sugar levels than ever before, partly because of an obsession with the flavours and textures that come with riper grapes, physically reducing alcohol in wines has become big business. Some wine producers have invested in their own reverse osmosis equipment that separates the combined alcohol and water components of a wine by filtering through a particularly fine membrane.They can then choose how to reassemble them (possibly, in very rainy years, using the technology to make a wine stronger). This equipment is not prohibitively expensive, but a bit of flavour tends to be left behind too. The Harry Potter-sounding spinning cone method, dependent on cumbersome and expensive vacuum-distillation technology, is where companies such as ConeTech of the US have been literally spinning money out of over-potent wines, with plants used to bring the alcohol down to palatable levels on virtually every continent.

But, as Dan Jago, Tesco’s wine supremo, put it, there is natural resistance among consumers to what are perceived as the ‘Frankenstein wines’ yielded by this sort of manipulation. What people really want, for those occasions when they seek a less alcoholic alternative (particularly midweek evenings and weekend lunchtimes, according to one piece of consumer research presented to us last week) is something that is naturally lower in alcohol. Having tasted my way through a few dozen current offerings of wines whose alcohol levels have been physically reduced, I must say I cannot blame them. It may be the fault of the raw material rather than the technique, but I have yet to find a wine with a deliberately reduced alcohol level that tastes anything like as good as one that is naturally low in alcohol.

Perhaps what is needed instead of all this tinkering is a bit more attention paid to the sort of wines that are naturally lower in alcohol than the big, beefy blockbusters that seem rather less popular now than they once were in markets such as the UK, Australia and New Zealand. (David Stevens reported that a trend towards lower alcohol is not discernible in his home country, flattering us by adding that this is because the American wine market is ‘less mature’ than the British one.)

By chance, the evening after the forum, I found myself tasting a range of wines from the Georgian Wine Society, a new importer of wines from the Caucasus, and found that several of them are labelled with the same strength, around 11%, to which several New World wines had been painstakingly reduced by David Stevens’ company TFC (stands for Twenty First Century) Wines.

One particularly obvious source of wines that have always been low in alcohol is Germany, many of whose wines are quite naturally between 7.5 and 11% yet can be chock full of flavour. There tends to be a trade-off, however. The grape sugar that is not fermented out to alcohol is left in the wine, so the wines with the lowest alcohol are the sweetest. And, it has to be said that global warming and an increasing taste for dry wines have resulted in a recent increase in the average strength of German wines.

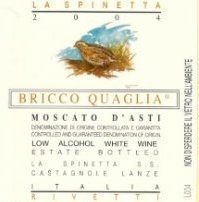

One seriously useful category of wines that are usually as light as 5.5% alcohol are sweet, fizzy Italianate wines such as Moscato d’Asti (La Spinetta's label for the single vineyard Bricco Quaglia, just 4.5% alcohol, is shown here) – infinitely more sophisticated than the Asti Spumante of old, and delicious at the end of a meal or as an aperitif. Matching them to food is more challenging as they are so unusually light and sweet.

Those looking for light wines that are bone dry could consider northern Portugal, whose Vinho Verde (‘green wine’, both red and white in fact) is made from grapes picked relatively early. TheTxacoli made in Spain’s Basque country is very like white Vinho Verde in its appley prickle on the palate. The best can be seriously refreshing and very winey, but they should be drunk as young as possible.

The problem with so many of the products (not all of them can legally be called wine) currently being manipulated to appeal to those looking for lighter wines is that they often taste of industry and technique rather than of wine, or they have been made from grapes picked so early that they are uncomfortably tart and thin. The bottom two whites and the two reds below are the most successful wines with deliberately reduced alcohol that I have come across. For ‘proper’ wines, it does seem as though 12-12.5% is a magic threshold. I can find dozens of recommendations at this strength but far fewer under 12%, and all of them are white.

RECOMMENDED REFRESHERS

WHITES

Virtually any Riesling from the Mosel, Saar or Ruwer Valleys, and any Moscato d’Asti

Verus Vineyards Muskateller 2008 Stajerska Slovenija 12%

£8.99 The Real Wine Co

Peter Lehmann, Clancy's White 2008 (Semillon/Sauvignon Blanc) 11.5%

£7.55 Slurp.co.uk

Hopler, Grüner Veltliner 2008 Burgenland 11.5%

£8.99 James Nicholson, William McKenna

Mineralstein Riesling 2008 Germany 11.5%

£6.99 M&S

Cuvée Pêcheur Blanc 2008 Vin de Pays du Comté Tolosan 11.4%

£3.99 Waitrose

Txomín Etxaníz 2008 Chacolí de Guetaria 10.5%

£12.95 Irma Fingal Rock

Ch de Hauteville, Poire Granit 2008 3%

£10.95 Les Caves de Pyrène (perry, not wine – but delicious)

Prima Luna Pinot Grigio delle Venezie 9.5%

£6.99 GIV UK (importer)

Nine Below Australian Chardonnay 8.5%

£7.99 Australian vintage (UK importer)

REDS

Mini Red Merlot Languedoc 11%

£5.99 Raisin Social (UK importer)

Altegé Merlot Vin de Pays de l’Hérault 10.5%

£8.26 www.bibendum-wine.co.uk

See my tasting notes on many more lower-alcohol wines.