Here’s an idea for a business opportunity: establish an oenological lab in Mallorca. Wineries on this Balearic holiday island are mushrooming yet there is no really serious outfit able to offer these relatively new winemakers comprehensive analyses and advice.

According to Javier Servera Ribas, whose family have a fair claim to the longest winemaking history in Spain, there were 10 wineries on the island 20 years ago and now there are nearly 100. When he returned from a 2004 internship with the particularly technically clued-up Rhône wine producer Jean-Luc Colombo, Ribas toyed with the idea of starting a lab himself but his family’s substantial winery in the little town of Consell in the middle of the island is clearly quite demanding enough. He makes Ribas’ reds, his sister Araceli the whites and rosado.

I spent a week on the island last month and there seemed to be new names on every wine list – not just new wine producers but Mallorcan grape varieties so recently rediscovered that they do not (yet?) feature on the lists of vines officially authorised for the two major appellations, or denominations, on the island.

Binissalem, named after the town next to Consell, is the oldest appellation and one best known for full-bodied reds made from the Manto Negro grape. It was joined in the 1990s by Plà i Llevant (a name that translates rather unprepossessingly as ‘flat and eastern’) in the south-east of the island. Its main grape is the generally fresher, lighter Callet. But both of these wine districts also produce a host of refreshing dry whites from the native variety known variously as Prensal Blanc, Premsal Blanc and Moll.

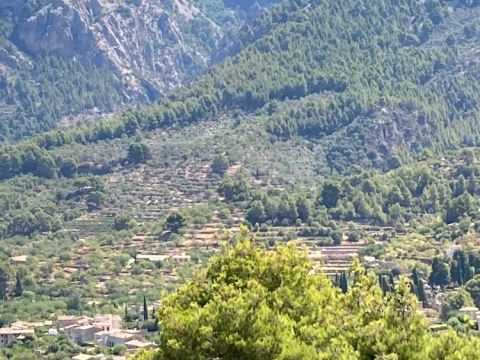

In 1891, when wine production in the rest of Europe had plummeted thanks to the predations of phylloxera, Mallorca had 30,000 hectares (74,130 acres) of vines churning out wine that was exported to fill the gap, but the vine-guzzling insect arrived eventually and by 1902 there were just 3,000 ha (7,410 acres). All over the island you can see abandoned terraces that were painstakingly constructed from the ubiquitous grey stones. Today there are fewer than 2,000 ha (4,940 acres) of vines.

Because of the influx of northern Europeans seeking holiday or retirement homes, land is expensive – too expensive to encourage vineyard expansion on any scale. So competition for grapes among all these wine producers is becoming increasingly fierce, more producers are small-scale and their wines are not cheap. Add to that new direct flights from Newark to Palma de Mallorca, one of Europe’s busier airports, and you have an island in which tourism is key.

According to Eddie Hart, proprietor of El Camino, one of Palma’s hottest eating destinations, for many years Mallorcan wine was of decidedly average quality because producers knew they had a ready tourist market that was none too discriminating. But the package holidaymakers like those I, as part of my travel-industry training, had to shepherd for a rainy week in Arenal in November 1971, for which they’d paid £18 all-in, have largely been replaced by a much more upmarket tourist.

And as restaurants have improved, so has wine quality. The children of those who used to grow grapes and then sell either them or bulk wine to the island’s bigger wine producers are increasingly starting their own labels and bottling their own produce. And quite a few incomers who invest in property are getting into wine production too, most notably Can Axartell, a particularly snazzy, gravity-fed winery recently built into a hillside south-west of Pollença in the north of the island by German cosmetics businessman Hans-Peter Schwarzkopf. (A British neighbour in the same valley told me it was known locally as Shampoo Valley because a member of the Wella family also has a property there.)

Like winegrowers the world over, in the 1980s and 1990s Mallorcan growers embraced international vine varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay and you can still encounter many a varietal Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot and Chardonnay on restaurant wine lists. But, as leading Mallorcan sommelier Joan Arboix puts it, ‘people don’t come to the island to drink what they can find at home’. Today indigenous varieties are all the rage – especially Callet, which precisely answers the current trend towards lighter-bodied, fresh reds that can be drunk chilled, heatwave or not.

Francesc Grimalt was the winemaker at Ànima Negra, for long the Mallorcan wine producer best-known off the island. With the help of Sergio Caballero, co-director of the Barcelona Sonár music festival, he has since established 4 Kilos wine estate, which is challenging Ànima Negra in that respect. 4 Kilos wines are imported into the UK by Indigo Wine and the US by T Edward Wines of New York but Mallorcan wines are generally easier to find in northern Europe, especially Germany; but both Decantalo and Vinissimus ship to the UK and have some interesting Mallorcan wines.

Grimalt played a crucial role in establishing the fashionability of Callet and tells the story of how, when in 1994 he was planting young Callet vines, still seen as inferior to imported French varieties, a local grower observed what he was doing and predicted he’d be selling their produce as Cabernet Sauvignon. Five years later, it was assumed he’d be passing off his Cabernet wine as Callet.

Over lunch at the wonderfully simple, wine-minded restaurant S’Estanc Vell in Villafranca in the middle of the island, Grimalt pronounced, ‘this is a beautiful time in my life; I’ve changed the wine rules in Mallorca’.

What he meant was that he has played a part in having indigenous varieties valued by wine consumers and recognised by the regulations of the local appellations. Although this is a process that has been happening so slowly that many of the newer producers prefer to label their wines simply Vino de la Tierra Mallorca rather than being limited to what is allowed by the rules of the Binissalem and Plà i Llevant appellations.

Grimalt has been a great promoter not just of Callet but of Fogoneu Mallorquí, which may be a parent of Callet and is usefully low in alcohol. (The Manto Negro of Binissalem is more like Grenache in that it ripens very unevenly, has to be picked pretty ripe and results in more alcoholic, less refreshing wines than Callet.)

I fell for another local grape, Gargollasa or Gorgollasa, which is almost Pinot Noir-like in its delicacy. It was rescued from extinction by the Ribas family and is still relatively rare – a bit like the fashionable aromatic white wine grape Giró Ros, which was rescued from extinction by wine producers Can Majoral and Toni Gelabert.

But there are yet more Mallorcan wine grape varieties whose DNA grape geneticists are still untangling. Escursac, rescued by Galmés i Ribot, seems to make slightly rustic but definitely ageworthy reds. Jaumillo is even more obscure and is an ingredient in a white wine that, unfortunately, didn’t make it to a big tasting of indigenous-grape-inspired wines kindly organised for me by Arboix. And Politxo, the impressive first wine we were served at an extraordinary el Bulli-like dinner at Brut restaurant in Llubí, is apparently made from Vinater grapes, so rare that they didn’t feature in my tasting either.

Thanks to the dry climate, which leaves Mallorcan vineyards relatively unscathed by the fungal diseases to which vines are prone, a very significant proportion of the wines I tried were certified organic, and many were just 12.5 or 13% alcohol.

One other general characteristic was how attractive and design-conscious the labels are – perhaps something to do with the relative proximity of Barcelona. No wonder Mallorcan wines are becoming increasingly trendy in Spain, or on what Mallorcans call ‘the peninsula’.

I went to Mallorca for a week’s holiday and, to my surprise, came across a wine revolution.

Favourite Mallorcans

VT stands for Vino de la Tierra, DO for Denominación de Origen. I scored all of these at least 16.5 points out of 20.

Sparkling

Raor, Prensal Brut Special Edition 2018 DO Plà i Llevant 11.5%

White

Miquel Gelabert, Sa Vall Selecció Privada, 2016 DO Plà i Llevant 13.5%

€22.70 El Mallorquin, Germany

Soca-Rel, Politxo 2021 Vino de España 12%

Red

4 Kilos, Grimalt Caballero 2019 VT Mallorca 12.5%

€31.99 Terra-Vinum, Hamburg

4 Kilos Callet 2013 VT Mallorca 13%

Can Axartell, Terrum 2019 VT Mallorca 13%

€20.90 Bodeboca, Madrid

Can Majoral Callet 2019 DO Plà i Llevant 12.5%

€13.35 (for the 2018 vintage) Vinos y Yo, Villafranca de Bonany, Mallorca

Ca’n Verdura, Vin Oblidats Escursac 2021 Vino de España 12%

£27.95 The Modest Merchant, London

Can Xanet, Sibila 2018 VT Mallorca 13.5%

€36 Peral Spanische Weine Delikatessen, Germany

Miquel Gelabert, Gran Vinya Son Caules 2014 DO Plà i Llevant 13.5%

€26.90 El Mallorquin, Germany

Mesquida Mora, Sòtil 2021 VT Mallorca 12.5%

€37.90 Lobenbergs, Gute Weine, Bremen, Germany

Ribas, Ribas de Cabrera 2018 VT Mallorca 15%

650 Swedish kronor Wine Dog, Stockholm, and various merchants in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland

Soca-Rel, Escursac 2021 Vino de España 13%

€17 Solo de Vino, Mallorca but ships throughout Spain

Tasting notes in Mallorca – boom, bust and renewal. International stockists on Wine-Searcher.com. See also Julia’s 2012 account of Mallorcan wine.