Norway’s best-selling wine is made by a black-metal musician who also curated an exhibition in the Munch Museum.

It’s easy to work out which wine sells best because, as in most Scandinavian countries, there is only one retailer of alcoholic drinks, in this case Vinmonopolet. Like Systembolaget in Sweden and Alko in Finland, the monopoly levies heavy duties on booze; they were all set up to discourage drunkenness. In Norway it’s a fixed mark-up of the equivalent of 54 p on every 75-cl bottle of wine, plus a further 22% of the price.

But, unlike the monopolies in Sweden and Finland, in Norway there is a maximum limit on total mark-up which, for most wines, may be no more than the equivalent of £8.36, and for their special category of higher-priced wines, is limited to the equivalent of £19. The result, as summed up by Stephen Fulker, the Canadian-born manager of Vinmonopolet’s flagship store in the Aker Brygge neighbourhood of Oslo, is that ‘in Norway cheap wine is expensive and expensive wine is cheap.’

This is why this narrow lane outside that flagship store sees a line of tents every freezing February for up to four weeks as wine lovers, or perhaps opportunists, queue up in anticipation of the annual arrival of top burgundies, including the fabulously priced wines of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. It is easy to understand the appeal of a wine that is elsewhere carefully allocated to favoured customers at thousands of pounds a bottle being available to anyone prepared to queue. La Tâche 2017, for example, was offered by Vinmonopolet earlier this year at £1,230, a quarter of its price in the UK. Considerable sums can be made by ‘flipping’ these wines, selling them on to a third party.

Although it is thought that some potential purchasers install students or others to queue on their behalf, there is a strict code of honour in the queue. No queue-jumping is allowed among those who take advantage of the tents and washing facilities provided respectively by Vinmonopolet’s landlord. The queuers call themselves the Grand Cru Network and even have their own song. I spoke to someone who was number 132 in line last February who told me mournfully that the last bottle of DRC wine went to queuer number 131.

But this is far from the only distinguishing characteristic of wine in Norway. Since my last visit there in the early 1990s, wine is no longer reserved for an elite crowd of connoisseurs. Per-capita consumption more than tripled between 1980 and 2010 as Norwegians enjoyed oil-fired prosperity.

Unlike in the UK, wine columns proliferate. I had a meeting with Norway’s top wine writers. Apparently there are about 30 of them in all but at my meeting there were eight, including six women, some of them with columns in three different newspapers. Merete Bø has 10,000 subscribers to her newsletter, which is offered as part of a £700 subscription to the newspaper Dagens Næringsliv, a sort of Norwegian FT. The biggest wine club, Norske Vinklubbers Forbund, has 4,000 members.

Bø and the popular stand-up comedian Thomas Giertsen have a wine podcast whose episodes can easily attract 30,000 downloads. And the three of us managed to fill the historic Chat Noir vaudeville theatre in Oslo with 350 wine lovers who paid the equivalent of £100 a ticket just to listen to us rabbiting on about wine while being served three small tasting samples. Above, some of them are seen waiting for us to arrive on stage.

Norwegians’ favourite wines are surprising. As an outsider, I would have expected full-bodied, warming reds to be the most popular in a country with long, cold winters but I’d be wrong. Dry German Riesling is top of the pops. The flagship Vinmonopolet store has a wall of the top names in Germany – infinitely more than in any shop I have seen anywhere else.

I was told that the Norwegian palate is attracted to high acid. (At least two of the dishes I ate during my three-day stay were garnished with underripe green gooseberries.) This would also explain the popularity of English sparkling wine in Norway, its most important export market. Apparently as many as 90 brands of English fizz make their way across the North Sea, and one store, in the little town of Sandefjord in the far south of the country, offers 51 English sparkling wines, 11 still white and six still reds – far more than retailers in their home country.

I tasted the wine deemed Norway’s own top sparkling wine, Komorebi 2022, made from four-year-old vines – the early-maturing, disease-resistant grape variety Solaris – grown near Kristiansand in the south. Its maker John Reidar explained that he often has to cover the vines in spring with a tight mesh to hasten the flowering. The scale is small. When I asked him about the size of his vineyard, he answered in terms of the number of vines (‘2,000 with the potential for 7,000’) rather than hectares.

According to a recent survey of the 150 vine growers in southern Norway by their association, no one currently grows more than 9,000 vines, but 19 of them plan to make wine commercially. For the moment, however, only two producers of Norwegian still wine are professional enough to sell to the monopoly. The others are allowed to sell their wine to restaurants or to visitors, but only by the glass and only if they have a licence. Selling anything alcoholic in Norway is bound by regulation. No advertising is allowed. And relations between the monopoly, importers and commentators are tightly regulated.

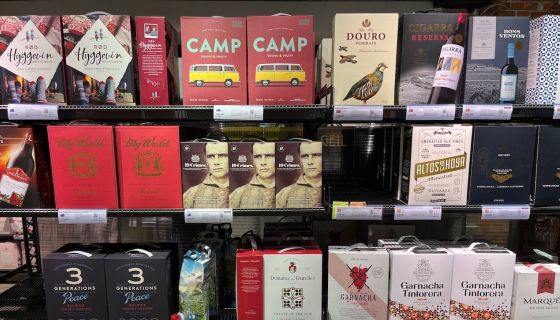

Vinmonopolet, now with 347 stores, celebrated its centenary last year and this year topped the poll in a public rating of all Norwegian businesses in terms of consumer satisfaction. Most wines are bought by the monopoly, as by other monopolies, on the basis of a tender followed by a blind tasting. So, boasted Fulker, ‘a small producer is just as likely to get on the shelf as a big one’. And, to judge by the heavy representation of the American Pinots of which Fulker is a fan, the staff seem to be allowed to follow their own taste. As well as the tender process, wines can be chosen as part of a special selection. As in Sweden, boxed wine, some of it looking most appealing (see main image), is extremely popular, constituting about half of Vinmonopolet’s sales by volume. And, like several other monopolies, they insist that bottles for their less expensive wines weigh no more than 420 g. There are benefits to having just one, powerful wine retailer.

But for a country with only one retail customer, there is an extraordinary number of wine importers, about 750, of whom most, according to one of the wine writers I met, are losing money because about 10,000 of the 28,000 wines on Vinmonopolet shelves last year sold fewer than 24 bottles. Many of the importers focus on Norway’s extremely lively restaurant scene instead.

And what about that Munch-loving musician? Sigurd Wongraven performs as Satyr in the band Satyricon but has deliberately chosen to brand his wines, mainly Piemontese and, of course, German, Wongraven rather than use his musical alter ego. They became so successful and sold in such volumes that Norway’s biggest wine company, Vingruppen, responsible for about a fifth of the entire Norwegian wine market, bought 90% of his brand for about £4 million in 2019. He still makes the blends, however, with, to judge from a couple tried in Bergen airport, admirable brio.

Drink like a Norwegian!

I scored all of these dry German Rieslings 17.5 out of 20 recently, with ‘ib’ meaning ‘in bond’ so minus UK duty.

Carl Loewen, Maximin Herrenberg 1896 Riesling trocken 2022 Mosel 12.5%

£135 per case of 6 ib Justerini & Brooks

Heymann-Löwenstein, Hatzenporter Kirchberg Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Mosel 12.5%

£156 per case of 6 ib Howard Ripley

Schloss Lieser, Lieser Niederberg Helden Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Mosel 12%

£174 per case of 6 ib Howard Ripley

Schloss Lieser, Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Mosel 12.5%

£174 per case of 6 ib Howard Ripley

Heymann-Löwenstein, Winninger Röttgen Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Mosel 12.5%

£192 per case of 6 ib Howard Ripley

Knewitz, Nieder-Hilbersheimer Steinacker Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Rheinhessen 13%

£213 per case of 6 ib Howard Ripley

Emrich-Schönleber, Monzinger Halenberg Riesling Grosses Gewächs 2022 Nahe 12%

£415 per case of 6 ib Justerini & Brooks

And these are old favourites.

Sybille Kuntz Riesling Spätlese trocken 2015 Mosel 12.5%

£32.33 Uncharted Wines

Peter Lauer, Ayler Kupp Neuenberg Fass 17 Riesling trocken 2020 Saar 12%

From $45 various US retailers

Eva Fricke, Lorcher Schlossberg Riesling trocken 2019 Rheingau 13%

£79 World Wine Consultants

For tasting notes and suggested drinking dates see Germany’s dry wines in London – 2023 releases. For international stockists see Wine-Searcher.com.