25 May 2022 Tuscan winemaker, Katia Nussbaum of San Polino, describes a conference desperately looking for solutions.

Under the aegis of the Châteauneuf-du-Pape winemakers’ association and the initiative of Birte Jantzen, wine writer and specialist living in Paris, a two-day conference was organised around the themes of vineyards and biodiversity. It took place earlier this month in the conference hall off the main structure of the imposingly magnificent yet austere 13th-century Papal Palace in Avignon.

I was invited as part of a journalists’ group, included because, although by no means an expert in the field, I am a winemaker and have written about ecology and vineyard philosophy in the past. As such, Jancis put me in contact with the inspirational Birte.

So I found myself lucky enough to savour four days on a conference tour of Avignon and Châteauneuf. I expected it to be stimulating and it was.

What I didn’t expect was to come back to the beautiful greenness of Montalcino in May only to discover how my eye for scenic beauty had altered in such a short time.

In only four days I had become accustomed to the sight of a quasi-industrial vineyard landscape devoid of greenery apart from hectare upon hectare of vines, broken up not by hedgerows but by monolithically tall tractors and the odd cypress or fruit tree. Although now, admittedly, it looks as though things may be changing in the southern Rhône vinescape.

This is how the conference was described in advance:

Vineyards & Biodiversity #1 Tomorrow’s Viticulture Starts Today! Two days where science and field experience complete each other, focusing on sharing pragmatic knowledge and exploring perspectives that have not yet been taken into consideration.

For the international journalist the experience was organised in two phases. Over the first two days we were to be taken to visit seven of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s top wineries as guests of the local wine producers, while the third and fourth days would be dedicated to the conference. I am sure that I speak for the group in offering them all our thanks for an absolutely wonderful five nights in their beautiful city. The whole event was a brilliant initiative and I hope it will be the first of many.

As we were bundled into our minibus on the first day of winery tours it felt like a cross between a school trip and a magical mystery tour. Our ‘motley crew of seven’ (as we later defined ourselves) six of us women, our nationalities spanning three continents, Europe, North America and Asia, we were biodiverse in all but a common interest in wine and issues relating to vineyard sustainability. Below, left to right, are Liz Gabay MW's wine consultant son Ben Bernheim, Reva Singh of Sommelier India, Liz Gabay MW, Pam Strayer (senior editor of Slow Wine Magazine and sustainability consultant for Vivino), Tanisha Townsend and me. Leila Salimbeni, semiotician and editor of the Italian magazine Spirito diVino, arrived later.

On a personal note I should add that for the past 20 years I have been producing wine in a UNESCO world heritage site of outstanding natural beauty where only 15% of the territory is covered by vineyards, the rest being woodlands, meadows, shrublands and land planted with fruit and cereal crops. This obviously has coloured my vision as to what it can mean for humans to live compatibly alongside nature. It was a Renaissance dream that has brought untold advantages to the wine producers of southern Tuscany, so we should be thankful and aim to never spoil what we have.

During this trip to the wineries of Châteauneuf-du-Pape I had the uneasy sensation of drowning in a river of contradictions. Rhône high tide indeed. I got the feeling that the producers of this appellation will struggle to think up answers to questions regarding biodiversity and sustainability, but am in awe of them for trying. While history has given them a fabulous terroir it has also left them a tricky agricultural and ecological heritage, one that it seems they are determined to resolve.

Inter-row cover-cropping may be harder to practise here than elsewhere owing to the presence of the celebrated galets roulés – flat, round rocks that blanket the soils in many of the vineyards – although perhaps this could be worked around. It is, however, true to say that the vines are more widely spaced than those in my Brunello-land, thus allowing each plant access to more minerals and water in an area of scarce resources. I cannot help but wonder how well it bodes for biodiversity, as there appear to be few nesting grounds for the wealth of ecosystem that ideally you would look for in a sustainable vineyard.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape is obviously one of the most noble of vignoble areas, being the birthplace of the French AOC system. Steeped in tradition, most of the wineries we visited claim aristocratic heritage (cousin of cousin of pope or duke or count etc) lending a grand sense of entitlement to their individual terroirs; so while we were coming to celebrate biodiversity I honestly felt bogged down under the weight of an almost ancien régime style of tradition.

My other perplexity lay in what appeared to be the high level of industrial monoculture and so it was heartening to see how a sensitivity to climate change lurked behind every conversation with the winemakers, particularly in relation to rising alcohol levels. Good: as nature pushes back at us we will be pressed more and more to find sustainable solutions.

From our meetings I heard that the vignerons believe the genetic wealth in the grape varieties permitted by their appellation will allow them to find answers to vine distress in unpredictable climatic times, yet the challenge they face is notable as any solutions through grape variety blends must depend on planting decisions taken many years ahead, as cuvées come from parcels of land rather than blending in the winery. This will require great skill, though I am sure they will find it.

And it goes without saying that the wines we tasted were glorious all the way through. I know I felt terroir in the glittering shine of their whites and glow of their reds, and I certainly saw the passionate enthusiasm of the winemakers, which was reflected in their real generosity and kindness.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape have set themselves the challenge of planting 42 km (26 miles) of hedges over the next few years. They call the task a marathon and every winemaker was proud to tell us about this. This idea is no doubt only the start of many more future plantings of woodlands, hedgerows and, I hope, ultimately some wilderness.

Of course, like everywhere, this AOC will have to work hard to reinvent their identity as new approaches are ushered in. This is always the problem with change, but the conference proved that this may be possible.

These are themes that struck me the most in our two days of winery visits, for which I was looking for answers in the following two conference days consisting of presentations by sociologists, urban planners, scientists and winemakers, with ample time given to question-and-answer sessions.

For me the most interesting seminars were specifically those concerned with the limitations of our conceptual frameworks when dealing with such topics as agriculture, conventional/organics/biodynamics or even sustainability. The questions these talks raised were of great complexity, leaving me with much to digest on my return home.

Jantzen had organised the order of speakers well and, like a symphony, it took us out on a journey. We started with the concept of landscape – what is it? When did the concept of landscape v humanscape emerge? What did it say about our cultural evolution as we separated culture from nature in Cartesian fashion in the 16th to 18th centuries?

The second and third movements took us through the science of geology, grafting, bird and insect populations, how to monitor them and help them increase, through ideas of vitiforestry, then soil microbiology and the benefits of healthy vineyard fungal networks and how to facilitate their development. What was perhaps missed was the conversation about fossil fuels and finding alternatives in the world of viticulture and winemaking. This should certainly be on the table for next time.

The last of the talks ended in a symphonic form of recapitulation where the hard data of the economics of sustainable practices in farming models as investment in our planetary future was explained to us in great detail.

The ultimate question being: how can we move beyond this to find synthesis? A modern integration of ourselves with the natural world, where we can flourish and allow the soil to flourish too, together with all the vast complexities of the flora, fauna, reptile, insect, fungal and microbiological life, to positively service each other in collaboration, as functional auxiliaries one-to-the-other for wholistic planetary health.

Prompted by the very first talk, given by Sebastian Giorgis, researcher of cultural landscapes, some thoughts come to mind. In pre-Cartesian times, culture and nature were not contradictory concepts. In medieval Europe, as in indigenous cultures, people lived inside as opposed to outside the world. The earth was seen as a protagonist with agency. Only with the development of early industrial capitalism and colonialism was nature seen as an inert resource to be exploited. Hence the evolution of landscape art in the post-Cartesian period, which posited Europeans as controlling outsiders, looking out over the panoramas of nature, the tabula rasa waiting to be circumscribed and controlled.

‘We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, the winding streams with tangled growth, as “wild”. Only to the white man was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was it “infested” with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery.’

Oglala Lakota Chief Standing Bear (1868–1939) recounting his people’s history as quoted in the The Nutmeg’s Curse by Amitav Ghosh

As Amitav Ghosh elucidates above, any human population reputed as savage or wild was categorised as part of nature, to be used as a resource, and in such a manner was slavery justified, similar to the way we use fossil fuels today to feed our contemporary economic models.

In this way we ‘terraform’ our world to fit our ways of seeing and use agriculture as a conduit through which to control our environment to satisfy our perceived needs. This will have great implications for viticulture, what it means and how to resolve the contradictions inherited from our past.

Is this the MeToo moment for nature, now we understand that through our entangled ecologies everything is connected?

On day two, ornithologist Katharina Adler gave a talk on birds and their beneficial effects on viticulture. She explained how it is better to hang nesting boxes outside vineyards to avoid stressing their young, while another talk by Emanuelle Porcher, ecologist from the Natural History Museum in Paris who works with teams of citizen scientists, gave us practical advice about how to monitor insect biodiversity in and around the vineyards. This was really interesting and I will certainly adopt some of her techniques in our vineyards.

Frédéric Chaudière, winemaker and president of the neighbouring Ventoux AOP, described in detail their new project for sustainability, Raison d’Être. Their plan for Ventoux for 2030 being to:

- reduce environmental impact by 30%

- protect the living

- cultivate life.

There were so many lively and wonderful discussions it would be impossible to mention them all.

Conferences like this bring these topics to the fore. It was more than encouraging to see that so many of us are looking for new ways to resolve these existential threats.

It was also overwhelmingly agreed that a lot of progress could be made with better coordination between universities and farmers, together with facilitated access to consultancy bodies and state enterprises with policies for open-source information dealing with ecological/sustainable issues.

So we must get moving, there is no excuse, no time to lose.

A final observation

In Avignon, legend has it that in 1314 a Templar, Jacques de Molay (pictured above), was arrested and condemned to death by order of Pope Clement V, ally to the French monarchy.

On climbing to the stake he furiously cursed the Pope and all Kings of France for the next 13 generations.

While Clement V suffered a painful death soon after, True Believers have it that the curse was lifted only when Louis XVI was beheaded in 1793.

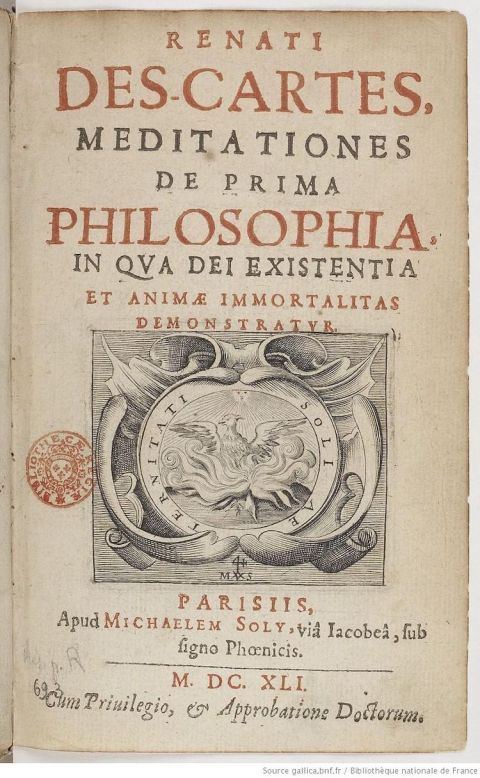

In a similar vein, Descartes published his Meditations on First Philosophy in 1641.

Around 13 generations later the Avignon Papal Palace has just witnessed the first conference on vineyards and biodiversity.

Next month the same venue will herald the opening of an extraordinary multi-sensorial exhibition by Sebastião Salgado showcasing his photographs from the Amazon forest: the ‘deep universe, where the immense power of nature can be felt like nowhere else on earth … that makes viewers think about biodiversity and the place for human beings in the living world’.

Is our Cartesian curse finally lifting? Congratulations to all involved. A magical mystery tour indeed!