Ten years ago Jamie and Jessica Hutchinson found themselves almost by accident at the Foire de Jambon de Bayonne. They loved this festival devoted to local Basque costume, evading bulls and ingesting pig products so much that they decided to decamp from their careers in the UK wine trade to settle in this corner of south-west France.

Jamie founded The Sampler, now three wine shops in London where serious wine lovers can pay for tastes of some of the finest wines in the world. He still owns a third of it and his experiences as an independent wine retailer played a major part in Jessica’s setting up Vindependents, a buying group for nearly 40 independent British wine retailers that is designed to ensure they will not be undercut by supermarkets and the like.

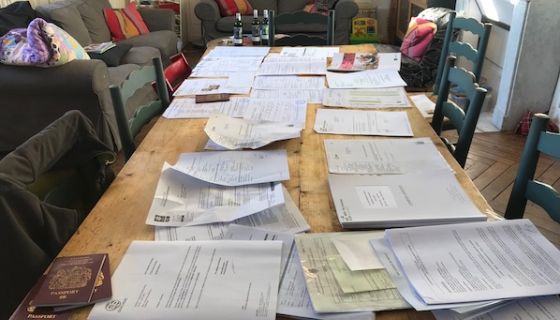

At the beginning of 2014, therefore, Jessica found herself with their two year-old daughter and no internet connection in a small rented house in the Pyrenées-Atlantiques trying to set up this complex buying and shipping organisation. Jamie was in London – ‘helping’, he interjected sheepishly as the two of them described their tortuous encounters with French bureaucracy over the last few years.

They had come to London to launch the first wine they have at last managed to bottle and release, a 2018 Petit Manseng Sec based on white grapes bought in from two different producers in the nearest appellation Jurançon. They are not allowed to call it Jurançon because it was not bottled within the appellation and was instead bottled by a mobile bottling line in the yard outside the house (see below) they eventually managed to buy in the tiny village of Audaux (‘Oh-docks’) halfway between Biarritz and Lourdes. But this is a very late chapter in the tale of their journey towards becoming wine producers.

They decided from the start that they wanted to grow vines as well as buy in wine, which is where their troubles started. This meant that they had to set up both an agricultural company, an EARL, for the former and a commercial company, a SARL, for the latter. To set up an EARL and buy the land (and indeed to do anything very much as they discovered later) the bank required them to be affiliated to the agricultural health insurance company MSA. But the MSA wouldn’t accept them until they had bought the land.

The effect of this Catch 22 was that it took them a year to open a bank account and they had to buy the hectare of land they’d identified as suitable for their own red wine production, reclaiming a slope (see below) that had not seen vines for 50 years, with personal funds from Britain. They then went back to get the crucial MSA number they needed, only to be told they didn’t have enough land to qualify, with 5.5 ha (13.5 acres) apparently the minimum area required. ‘We’d have done better to have had a third of a hectare of piment d’espelette', commented Jessica grimly, referring to the legal minimum for the famous local red pepper.

MSA went to the trouble of sending two people to the Hutchinsons’ house to check that they did indeed have only one hectare. They were told they would have to go to the alternative insurance organisation, the RSI, who told them no, you are farmers so you’ll have to go to the MSA.

Buying the land was also an extended process because of France’s (rather admirable) SAFER protocol whereby land may be sold only if no young local farmer wants it. So it was not until 2017 that the Hutchinsons were able to buy the steep slope by their house. If they’d had that magic MSA affiliation, they could probably have qualified as needy young vignerons themselves. Instead of which they paid extra to fast track their SAFER approval.

They then had to apply for plantation rights. These have been tightly controlled since the EU adopted special measures in 2007 to drain the European wine lake, and are granted only during a four-week period every May. To apply you need another number, this time allocated by the customs officials, the douanes. So Jamie and Jessica set off for Pau to get their number but things did not go well. The douanier got a map out, identified where their hectare was, and laughed in their faces. (The Hutchinsons live about 10 miles outside the border of the nearest appellation, Jurançon.) Eventually, over four hours with the douanier, they were taught how to log in to the plantation rights website, and told that the crucial log-in details would be sent to them. By post.

When the douanier warned them that his colleagues would be coming to inspect them, with dogs and handcuffs, and that during the inspection they would have to stand in a corner, they laughed and he didn’t.

Eventually they received the precious log-in, only to find that they need a CVI number to apply for plantation rights on the website. Jessica rang her favourite douanier to ask why he hadn’t also give them their CVI number. Simple. It wasn’t his responsibility but the job of his colleague downstairs.

They subsequently learnt that they needed a CVI for each of their companies and eventually managed to apply for and be granted their plantation rights. But there was another problem. To fill in the application you needed to know which appellation you would be applying for – difficult in the Hutchinsons’ viticultural wilderness.

At present they think they will use for the Syrah they have decided to plant the same one they are using for their bought-in Petit Manseng Sec, the local IGP, one step down from full Appellation Contrôlée, IGP Comté Tolosan. It’s perhaps unfortunate that it’s named after a city 100 miles away with no Basque connections whatsoever, but the Hutchinsons feel that the alternative, the geographically unspecific Vin de France, would be a bit of a cop out – not least because, partly because of the warmth of the welcome they have received from their fellow villagers, they want put Audaux on the map. ‘Eventually we’d love to have Audaux have its own appellation', Jessica told me. Though whether she could tolerate the necessary protracted paperwork is surely debatable.

With the granting of planting rights came the requirement to attend a two-day course on the buying, storing and application of agrochemicals, even though the Hutchinsons intend to use only the Bordeaux mixture sanctioned by organic regimes.

The planting rights came through on 18 August, which would have been too late for the usual spring planting if they had needed to order a special combination of rootstock and scion, but fortunately what they sought was already available from the nursery. To prepare the ground they had to acquire a chainsaw and cut down a few trees, Jessica reported. ‘Well, I’m still alive', said Jamie, defensively.

Once the site was ready 2,200 Syrah vines were delivered, and planted by a 71-year-old local expert and three young lads over seven busy hours in June this year. Then Jessica had a brainwave. She rang the douanier to tell him they had now planted their vineyard. Uh oh. They should have submitted a déclaration de plantation beforehand, apparently, though this was never spelt out. She got away with it and they now look forward to the first small harvest of their own red wine in 2022. ‘They know me now at the douanes', she smiled. Fortunately her previous job as a burgundy broker has left her with working French.

In advance of the production of their Petit Manseng Sec, their commercial company had to leave a caution (deposit) of €34 with customs against any duties payable. The total eventual duty bill for their 2,400 bottles was €75, so low are wine duties in France.

But before launching their dry white wine, there was another major hurdle to be overcome: the mandatory official tasting. The regulations for a dry white IGP Comté Tolosan stipulate that the wine has to be aromatic, floral and fruity. But the Hutchinsons, great admirers of the potential of the local Petit Manseng grape with its naturally high extract and acidity, decided to pick it really ripe and ferment it in oak like their beloved white burgundy – used barrels from smart Bordeaux châteaux in this case. The strength of their first vintage, 2018, was 14.7%, dangerously close to the legal maximum for this IGP, 15%. So the wine was very unlike what is officially required and apparently only just scraped through the tasting panel.

The high level of volatile acidity that results from their production method is another worry. If it were to exceed the official maximum, they would have to pay for someone to come and cart their wine off to be distilled into industrial alcohol. No drinking up of the rejects.

While they have had their problems with French bureaucracy, the Hutchinsons, who now have two daughters and a resident grandmother, are wildly enthusiastic about their neighbours. Once it became clear that their children would go to the local school, they have been thoroughly absorbed into the local community, and cunningly offered a village-wide feast in exchange for help with sorting their Petit Manseng grapes (see below). They’ve been told that this is the first time the villagers have all sat down together for a generation, ever since the advent of mechanisation in the fields.

There is the odd culture clash, however. The Hutchinsons use the superior Petit Manseng grape for their dry wine whereas Jurançon producers tend to reserve it for the sweet moelleux version, locally much more admired, and use the less exciting Gros Manseng grape for their dry wines. When Jamie explains that sweet Jurançon is difficult to sell in the UK, his neighbours are mystified. ‘But what do the British drink with their foie gras?’

Some favourite dry Petits Mansengs

Jurançon is the Petit Manseng stronghold but its obvious quality means that it has now been planted far and wide. It can also age very well. All of these dry examples should still be going strong.

Ch Lapuyade, Dentelle 2015 Jurançon Sec

Clos Lapeyre, Evidéncia 2015 and 2014 Jurançon Sec

Cauhapé, Geyser 2016 Jurançon Sec

Domaine de Souch 2009 Jurançon Sec

Cabidos, Comte Philippe de Nazelle Petit Manseng Sec 2009 IGP Comté Tolosan

Domane d’Audaux Petit Manseng Sec 2018 IGP Comté Tolosan

La Pupille, Piemme 2015 IGT Toscana Bianco

Horton Petit Manseng 2014 and 2016 Orange County, Virginia

Michael Shaps Petit Manseng 2016 Virginia

Domaine Franco-Chinois Petit Manseng 2014 Hebei, China

Topper’s Mountain, Barrel Ferment Petit Manseng 2013 and 2011 New England, Australia

Churton Petit Manseng 2015 and 2013 Marlborough, New Zealand

You can find tasting notes on these wines in our tasting notes database. Stockists of these or younger vintages from Wine-Searcher.com.