One of the biggest challenges facing the wine industry (indeed, any industry) is to get a collective grip on what sustainability really means. It goes way beyond simply defining the word and, as many are now beginning to realise, real sustainability goes way beyond what any single certification aims to do or can achieve, whether organic, biodynamic, carbon neutral, BCorp or Fairtrade (or the myriad other certifications out there).

Now is surely the time not just to sustain, but to regenerate. The basic premise of regenerative agriculture is that soil health underpins life itself, and that it is only by beginning with the soil, which has been catastrophically degraded across the globe by anthropogenic pollution, that we can address the damage to the earth’s ecosystems.

Stephen Cronk, an Englishman in Provence, faced that very question when, after 10 years of producing négociant rosés under his Mirabeau label, he finally bought his own vineyards in 2019. Chemically farmed for years, the soils were exhausted, denuded of organic life, and the vines needed to be propped up with artificial fertilisers. Even before the sale was complete, the transition to organic farming began, but he quickly realised that it was going to take much more than simply following organic regulations to bring the soils and the entire property back to life. Organic certification, he said, ‘was just doing less of the bad stuff’. At the same time, Cronk, first and foremost a businessman, recognised that there had to be a way to do this without it crippling the business in any way.

Cronk started searching for help. ‘I couldn’t work out how to learn to farm the way I felt I should be farming.’ He felt an increasing sense of urgency as his research led him to realise that ‘things are getting pretty close to be unable to change; we need to move quickly’. Then somebody sent him an article written by Eric Asimov in the New York Times about regenerative-farming champion, Mimi Casteel.

There were pictures of sheep and ducks and wildlife on the farm, and Cronk thought, ‘I like the look of that because’, he said smiling, ‘it was a vineyard’. So 18 months ago, Cronk, Casteel and Jesper Saxgren (a Danish eco-consultant who specialises in permaculture, sustainable development and environmental management) started talking on Zoom calls. ‘We basically realised that there wasn’t a great resource for wine farmers like me to learn how to become regenerative. So [Saxgren] said, “Let’s create one. Let’s create a resource where people can come and learn from others … can learn how to take those baby steps.” And here we are today.’

The ‘here’ Cronk was referring to was a packed room in 67 Pall Mall, London, where the launch of the Regenerative Viticulture Foundation (RVF), a new, global non-profit organisation, took place on 28 March 2022.

Cronk, in a manner unexpectedly quiet, unassuming and modest for someone who runs a pretty mean brand-marketing machine, proceeded to give a thoughtful, heartfelt and well-considered frame of context for why the RVF had been formed and what they hoped to achieve. I’ve snipped some salient quotes from his inaugural speech below:

‘As you know, we’re at a critical point on this planet, a tipping point, in terms of biodiversity loss, degraded soils and climate change … We, at a species level, ceased to be hunter gatherers 12,000 years ago. We learned how to farm, we learned how to create communities, we learned how to specialise … We started to modify our natural environment through cultivation, irrigation, deforestation … Recently, we’ve become even more ruthless and efficient, at farming in particular. And particularly since the Second World War, we’ve seen the adoption of commercially available pesticides, herbicides and synthetic fertilisers, enabling us to become even more effective at eliminating competition, diseases, predators and so on.

‘And perversely, then, we’re having to put synthetic, man-made material into the soil; we’re having to put back in everything that we’ve taken out … We’ve become incredibly efficient at food production, to the extent that we actually now produce more food in the world than we consume … Or, perhaps, we produce more calories than we consume … We’re continuing to cut down forests and plant more crops to feed the world that we can already feed … All this is leading to agriculture’s impact on the environment: climate change, biodiversity loss, and mass species extinction. Agriculture is a major cause of greenhouse-gas pollution and climate change. And climate change is now disrupting agriculture. So it’s a man-made vicious circle.

‘And yet the irony is that Mother Nature is incredibly forgiving and is able to regenerate herself, but we need to unlearn what we’ve learned and let her show us the way … The optimism Nature has shown us is incredible [there he was referring to the fires that wiped out Domaine Mirabeau’s crop]. Regenerative agriculture is becoming more and more commonplace in general agriculture. Some of the largest food companies in the world are adopting their versions of regenerative agriculture, so it is happening, but we in the wine world need to do our bit, and we need to move away from this concept of monoculture, starting to actively encourage plant, animal and microbial life in the soil. The thing is, we can’t just sell our tractors and ploughs, and let nature take over the vineyards. We need to start taking small steps, to reintroduce nature in an intelligent way that helps us maintain our vineyards, maintain our yields, and ultimately make better fruit. So, if we could make better-quality fruit, better-quality wine, less impact on the environment and lower input costs, then what’s not to like about this way of farming? It’s really as simple as that.

‘So, the purpose of the Foundation is to help build the knowledge of how to move towards regenerative viticulture in a way that doesn’t disrupt our businesses, migrating towards a holistic way of farming. Regenerative farming is like a toolbox provided for us by nature. We need to get proficient on how to use it effectively.’

The RVF is led by a crack team of trustees. As well as Cronk, with a background that encompasses wine importing and telecoms, the board comprises: Danish ecologist Jesper Saxgren; Oregon wine producer and forestry botanist Mimi Casteel; English Dr Alistair Nesbitt, a viticulture climatologist with degrees in both viticulture and oenology; Australian Richard Leask, vineyard owner and manager and Nuffield scholar (research project: regenerative agriculture); French Ivan Massonet, owner of Domaine Belargus in Anjou, chair of PAI Community, and head of PAI’s ESG and sustainability team; English Martin Gamman MW, UK marketing manager for Joseph Perrier Champagne and owner of 10 ha (25 acres) of regeneratively farmed land in Gloucestershire; and Justin Howard-Sneyd MW, who needs no introduction on this website, but could be described at any one time as vigneron, wine-industry consultant, wine marketer, wine-technology innovator, wine educator, Master of Wine, council member and head of membership committee for the Institute of Masters of Wine, and producer of great Roussillon wine.

It was Howard-Sneyd who took the stage after Cronk, primarily to explain exactly what regenerative viticulture (or regenerative agriculture for that matter) is. In many ways, the answer comes down to one simple word: soil.

The RVF website says that, ‘Regenerative agriculture is a conservation and rehabilitation approach to food and farming systems. It focuses on strengthening the health and vitality of farm soil, increasing biodiversity above and below ground, improving the water cycle, enhancing ecosystem services, supporting carbon sequestration, and increasing resilience to climate change.’

Regenerative viticulture, then, is farming vineyards ‘based on the understanding that the health and fertility of soil is the foundation for life above and below ground and that it is the most important component of healthy terroir’.

Several people in the audience wanted to know, ‘How is this any different from organic, biodynamic or sustainable viticulture? Is this not just yet another buzzword, another philosophy, another set of rules, another certification?’

Howard-Sneyd explained that, while there are many shared practices and principles between all these frameworks and conventional* farming, there are critical differences. Organic and sustainable farming is primarily about excluding or restricting the use of synthetic chemicals to within regulatory boundaries. In fact, he pointed out, organic/sustainable farming practices have the potential to be extremely damaging to soils, such as regular tractor use, especially on wet soils, causing compaction, and the use of copper, which causes toxic contamination of the soil. Organic vineyards are audited and then approved if the practitioner is following all the rules: the farm records are checked to verify inputs, management processes and outputs. The success of regenerative viticulture can be measured only by the increasing health of the soil and surrounding ecosystems.

It has been argued that regenerative viticulture is simply a repackaged version of biodynamics, and the only differences are that there is no global certification body (although we will be publishing an article on the first such thing), and no cow horns are required. But there are fundamental differences. While biodynamic viticulture takes a holistic approach, aiming for the health of the local ecosystem, certification is dependent on the wine producer following generic regulations and mandatory practices which may well be unsuitable and/or unviable for different locations and circumstances. Regenerative viticulture is not a set of rules but, as Cronk pointed out, a toolbox that can be adapted according to site, specific circumstances and vintage variation. Regenerative viticulture also looks beyond the crop being produced and takes into account natural biodiversity, carbon sequestration, water-cycle management and climate-change resilience.

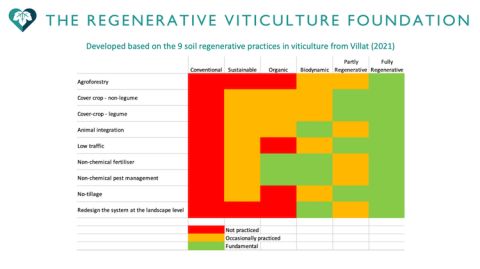

He put up a slide of a table compiled by Jessica Villat, from her research paper in 2021 entitled, ‘Down to earth: identifying and promoting regenerative viticulture practices for soil and human health’. It shows the nine principal practices of regenerative viticulture and then compares the employment of each across six of the most common viticultural approaches. The colour-coding is clearly designed to be emotive, but it’s a striking overview.

As well as building soil health, which I will go into in more detail in part two of this series, regenerative agriculture, Howard-Sneyd said, ‘will massively lock up more soil carbon; increase biodiversity (diversity creates stability in the system); and reduce input costs such as fertiliser and fuel’. As the panel discussion proceeded after the presentations, it quickly became clear that the argument so many use for not becoming organic or biodynamic, economics, becomes a driving imperative for implementing regenerative practices. Particularly when set against the backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which threatens global supply of gas, oil, high-demand metals including copper, fertiliser, wheat and various other foods, regenerative viticulture is a much more profitable proposition because it does not rely on synthetic chemicals, heavy machinery use and high-energy inputs.

Unlike organic and biodynamic viticulture, it doesn’t require a deadline-driven, relatively fast overhaul (most organic certifications require a three-year conversion period) which may result in a serious dip in yield, and there is no red tape, complicated paperwork, bureaucratic short-sightedness or certification costs. Regenerative viticulture is not a closed club. You can be 100% conventional (how I hate that term*), organic, biodynamic, BCorp, carbon neutral or just bewildered – anyone can implement just one of the nine main practices and the soil will start to improve. No one is checking, no one is judging, but now there is a globally networked community of people ready to provide support, encouragement and advice.

As I understand it:

- the biodynamic approach has metaphysical and spiritual roots, is framed by rules and measured by compliance

- the organic approach has ethical and traditional (pre-war) roots, is framed by rules and measured by compliance

- the regenerative approach has scientific roots, is framed by investigation and measured by ecosystem health (something I'll discuss in more detail in part two).

Good science always tests existing theories, tests deep-seated beliefs (even personal ones), and always asks questions. My strongest takeaway from what I heard was that while the science of regenerative viticulture is founded on the soil, the philosophy of regenerative viticulture is asking questions and staying open to what nature has to teach us.

*'Conventional viticulture' is a term that has fallen into mainstream use and I strongly object to it. The Oxford English Dictionary defines conventional as 'Based on or in accordance with what is generally done or believed ... greatly or overly concerned with what is generally held to be socially acceptable'. This implies that an agricultural system, now recognised to be one of the key drivers of climate change, soil degradation and biodiversity loss, is 'socially acceptable' and 'generally done'. Socially acceptable it most certainly is not. 'Generally done' is true, but only since well after the Second World War, and those 70-odd years, set against the time that humankind has been managing the earth's resources for food, can scarcely be considered 'conventional'. 'Conventional' is, plain and simple, whitewashing a crime against the planet, in my view. We should, instead, be using the much more ugly, but much more realistic term of 'synthetic-chemical viticulture'. Rather than demanding that producers jump through hoops and pay a premium to prove their non-chemical credentials, regulatory bodies should legislate that every producer using synthetic chemicals on their vineyards and in their wineries should have to, by law, list them on their wine labels, and pay for the privilege, thus subsidising those producers who are trying to protect our planet for future generations.