23 October 2020 Two sommeliers, on different sides of the Atlantic, tell their stories of grit, spit and triumph.

Wine Girl

A sommelier's tale of making it in the toxic world of fine dining

Victoria James

Fleet

ISBN 9780349726274

£16.99, $26.99

‘She was full-bodied but with a short finish.’

In describing herself as a ‘juxtaposition of blue blood and blue collar’ (one grandmother an orphaned Tennessee cotton picker and the other a Piemontese countess), Victoria James explains why she was perfect sommelier material – ‘essentially a highbrow servant’.

Her upbringing as one of four siblings swung between neglect at the hands of a severely depressed mother and abuse at the hands of a tyrannical father. She grew up in a low-income household, dumpster diving for food coupons on her father’s instructions and wearing shoes with holes in the soles, so in order to earn a few extra bucks, James threw herself into a server job at the local greasy spoon. She was 13.

At 14 she learned the a–z of cocktails by becoming an unofficial drink runner at the casino where her drunk father gambled. Age 15 she was raped by a regular customer from the diner she worked at. She started smoking pot and drinking alcohol. She starved herself to try and disappear. By 17 she was smoking black-tar heroin.

Being convicted for driving under the influence, a dusty Wine for Dummies, and the combination of Amarone and Parmigiano Reggiano changed her life. She started to put herself through wine school before she even knew what oak ageing meant. Two months after she turned 21, she landed a job as a sommelier at Aureole in New York and passed the Court of Master Sommeliers’ stage 2 exam to become the youngest sommelier in the country. By 25, she was wine director of a Michelin-starred New York restaurant.

So, we have another memoir written by someone under 30 who’s had a meteoric career path despite an underprivileged start in life. Rags to riches, overcoming adversity, brilliance and drive. Another prodigy, with the book, the pin and the pay check to prove it.

Yes and no. It could be read as an autobiography of redemption and personal triumph, but I think that would be to miss the much more powerful and pertinent message. James has pulled back the masking flats hiding the backstage of the New York dining scene. And it’s not a pretty sight.

It makes for a pretty sordid glance into systematic misogyny, abuse, discrimination and corruption. Joining the ‘fine-dining caste system’ and becoming a sommelier, she entered a world that was ‘almost completely male dominated. Even more rare was anyone of colour, let alone women of colour. In the whole room of hundreds of wine professionals [at an annual sommelier wine conference in Dallas], I spotted only one black person. The sommelier pool was a sea of older white men.’ At that same conference, she describes how ‘an MS seen as the godfather of the masters slapped me on the ass and congratulated me, “You pretty young thing, love seeing girl sommeliers.”’

Over a period of 15 years, she is patronised, belittled, humiliated, sexualised, assaulted and raped. If that sounds attention-seeking and overblown, James has scrupulously tracked dates and places. Although some names have been changed, she’s factual, and in a highly litigious culture she (and her publishers) would run enormous risk in publishing untruths about these still-operating restaurants and their staff.

Much of the abuse came from within the hospitality trade. From a restaurant owner who told her, ‘Women are good at spending money but not saving it … Why would I put a girl in charge of my restaurant’s pocketbook?’. From fellow sommeliers who snickered openly at tastings, ‘Is she supposed to be some effort at diversification?’ and ‘Who brought Barbie?’, calling her a stuck-up bitch if she wouldn’t get involved with them, and somm slut if she did. The ‘tasting note’ at the top of this page is how one sommelier colleague described her after she unwisely had sex with him (because she thought they liked each other).

A sommelier-school instructor openly mocked her in class with, ‘ass and a pair of tits here wants to tell us [men] how to taste’ and a company rep who wouldn’t pour her the red wine because, ‘Well, most women find the red wines too powerful. They only like the white and rosé.’ One manager told her that the reason women shouldn’t work in fine dining was because their menstrual cycles meant that they’d have to go to the bathroom during a 12-hour shift. One of her bosses repeatedly raped her in his office and in the wine cellar.

‘Guests’ were no better. There was the wealthy businessman who wanted her to serve his $1,200 bottle of wine while sitting in his lap. When she refused, he screamed at her, ‘Bitch, I bought you!’ Despite long hours sweating over seating charts to make sure that the restaurant didn’t offend the socialites, one woman complained about the window-view location of her seat: ‘How can I enjoy my meal with a view of those immigrants?’ When she approached a couple and started to discuss the wine list with the husband, who was the one reading it, his wife screamed at her to get away and the next day wrote a scathing review about ‘women like that who only get ahead by laying on their backs’. To avoid another interaction like that, she chopped her long hair off and wore layers under her suit to hide her body.

‘Corkage cowboys’ brought hookers to the two-Michelin-starred restaurant, waving their ‘priceless bottles’ around, snorting cocaine in the restrooms, vomiting in basins and quite often refusing to allow their female companions to eat anything. Wine glasses, caviar spoons and soap dispensers were stolen. Guests complained if the reservationist had an accent, pinched the bums of servers and would ask James to mix cocktails, saying ‘Shake your t***ies for us again, wine girl’.

Perhaps one of the most distressing implications is that overt and even violent sexual innuendo and sexual assault is not only common in the world of fine dining, but it is acceptable. It’s normalised. Money buys entitlement. The era of plantation owners may not be so very far away after all.

It’s not just sexual abuse and discrimination that hospitality workers put up with. James describes restaurants taking money out of staff pay checks to ‘pay’ for the once-a-day staff meal (made from food that for one reason or another cannot be served to the guests) – not a meal staff could opt out of, thanks to regulations banning staff from bringing their own food into restaurants and no opportunity to leave the building during their 12-or-more-hour shifts.

‘Restaurants’, she went on to say, ‘fetishize long hours of manual labour’, describing shifts that would sometimes start mid morning and run until beyond sunrise the following day when the last guests left. She describes losing 30 pounds (nearly 14 kg) in the first few months of one job. Staff took their behavioural cues from those in charge, treating each other with contempt and suspicion. Being ignored, shoved, threatened, patronised, mocked, pinched, elbow-jabbed and gas-lighted by colleagues was just part of the workplace culture. ‘The manual labour of Marea, the sheer exhaustion, the insane pressure, all stripped me of my humanity,’ writes James.

And if you’re thinking that at least the patrons are respected, you probably haven’t heard about PITAs and whales – Pain In The Ass and big spender, respectively, if not respectfully. It’s common practice in New York City apparently for restaurants to share a database of information on their guests: who messed the bathroom up (yes, there is a camera in the passageway), who stole a caviar spoon, who spends too long at the table and who doesn’t tip well. HWC next to your name means ‘handle with care’ – you’re a difficult prat and likely to get ugly if things don’t go your way. ‘When you walk into a Michelin-starred restaurant, extensive research has been done on you’, and you’re carefully scanned for clues – from your finger nails to your handbag, mental and physical notes are made. If you’re young, fashionable and beautiful, you’re window dressing – you’ll get a table in full view of everyone. Struggling to get a restaurant booking? You may have been blacklisted.

With the cheating and discrimination scandals that rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers recently, it’s going to be no surprise that James flagged up corruption outside the restaurants. ‘The whole sommelier certification industry is unregulated, and therefore there is incredible potential for abuse. Young women like me are especially easy targets since we are desperate to fit in.’

She points out that no one is willing to talk about it because no one wants to question the validity of the pins and certificates that are handed out, or admit that all the time and money they have sacrificed may be for something of no real worth. Added to that is the psychological pressure of the job. Sommeliers, she writes, ‘misconstrue their position. They become accustomed to the habits and conversations of the rich and start to think of themselves on that level.’ They go into enormous debt to buy wine and eat out at places they can’t afford. Alcoholism and drug use is rife. They end up in the pockets of companies who ‘pay to play’, plying sommeliers with free wine and slap-up meals to get their wines listed.

There is, without doubt, a dark underbelly to parts of the industry. Both Jane Lopes in Vignette and Bianca Bosker in Cork Dork tell similar stories. Of course, like Victoria James, Lopes and Bosker are also relentlessly driven, incredibly hard-working, highly intelligent, and – in James’ words – ‘driven to prove myself among my peers’. All three were drawn to wine by a fascination with flavour and the intellectual and emotional connection with place. All three quickly found that success in the industry was more like survival. Their stories of drug and alcohol abuse, sleep deprivation, exhaustion and burnout could be attributed to nervous temperaments, not being tough enough. But this is neither the military nor A&E. Should one have to be hard as nails to serve food and wine? As one Frenchman put it, ‘it’s not a game; it’s a bloodsport’.

James's accusations could be seen as sour grapes. One could also argue that it’s poor timing. To be bad-mouthing the restaurant industry still reeling from the blows of COVID-19 is, at the very least, insensitive (although bear in mind that the book was published at the beginning of April 2020 in the UK and even earlier, with a different subtitle, in the US, so written long before that).

It’s neither. James is currently at the top of her game, beverage director and partner of Michelin-starred restaurant Cote in New York, wine writer, educator and speaker. She puts her own career and reputation at risk for writing such a frank book. But it’s also crystal clear that she cares passionately about the industry. This is not a pity party – it’s written more for other women caught in the place she was. This is not revenge arson, wanting to see the whole show go up in flames – it is a clarion call for change.

In her dedication, she writes ‘to all the women in the world of restaurants … it’s our time now’. In her acknowledgements she continues, ‘I hope my story will give young women all over the world courage to share their stories, take charge of their lives, and empower others. Let’s stand together for social justice and create positive change. Wherever you are, don’t let anyone stop you for telling your truth.’

Whether the issue is unique to New York, the US, big cities or the world at large, it’s time we pulled the curtains back. Diners must choose to know as much about the humanity of the restaurant they’re eating in as they want to know about the provenance of the food they’re eating.

Tasting Victory

The life and wines of the world’s favourite sommelier

Gerard Basset

Unbound

ISBN 9781783528608

£25

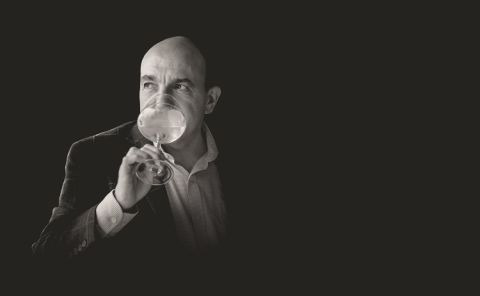

It’s testament to the extraordinary tenaciousness, discipline, drive and focus of Gerard Basset that in the last two years of his life, despite the physical and emotional battering of cancer and chemotherapy, he managed to write and complete his memoirs. It’s testament to his generous, humble spirit and the many lives he touched that when Unbound needed £14,000 to cover the costs of publishing the memoirs, crowdfunding had raised 100% of the money needed within four days and the final amount raised was 250% of the target.

His editor, Felicity Carter, wrote to Jancis saying, ‘The only downside to working on the book was telling Gerard we had to cut at least 50,000 words, many of them documenting the triumphs of other sommeliers. It was the only thing we had a disagreement over, because he wanted to give everybody their full due and celebrate them for their achievements.’

His own achievements were astounding, particularly in light of his start in life. After a lonely, fairly tough childhood and several years getting fired from one menial job after another, it was – of all things – a football match in Liverpool that changed his life. A football match he nearly didn’t get to! Bacchus (and a high-ranking customs official) must have been smiling on the 20-year-old, green-painted French boy who managed to get from Marseille to Liverpool without a passport. The most unexpected thing of all, that day, was that Gerard Basset fell in love with Liverpool.

He packed up his life in France and moved to England, barely able to speak a word of English. His first job was as a kitchen porter on the Isle of Man.

It certainly wasn’t an introduction to fine dining. In 1979 on the Isle of Man, the dinner menu at the hotel included orange juice as one of your three starter options, and on curry night (Thursday) the chef spiced things up by dyeing the rice a different colour each week: bright red, bright yellow, and even green on one occasion, in honour of Gerard’s football team, St-Etienne.

His tenuous grasp of English nearly cost him his second job when he answered the question, ‘What are your criminal convictions?’ on the application form. ‘It would be too long to explain’, he wrote. The interviewer gravely informed him that his answer was not sufficient; he was going to have to come clean. Basset writes, ‘I cast about, not sure how to begin. I rearranged my face into a look of concern, as befitting such a serious topic, and launched into it. “Criminality is damaging to society. But perhaps there are better ways to deal with it that society should experiment with …”’ – I can’t have been the only person to have burst out laughing.

The book is full of these anecdotes, Basset gently poking fun at himself and the people around him. He is (almost brutally) honest throughout the book, mostly about his own shortcomings and mistakes. But he is equally frank about his achievements, some of which Jancis touches on in Farewell Gerard, far too early. He admits, that ‘in spite of my rather average natural attributes, I managed to become the most titled person on the planet in my chosen profession of sommelier. There is no doubt that there is a vanity aspect in my character, which makes me feel very happy and quite proud about that, but then just like a sports champion, I wanted to win as many titles as possible, so why not – I have earned that feeling of pride and my moment of vanity.’ Despite his confessed vanity, I found that he wrote evenly about the disasters and successes, the struggles and rewards, the headiest and the lowest of moments, whether running hotels, taking part in sommelier competitions, and achieving his Master of Wine, MBA, Master Sommelier and MSc Wine Management.

Where so many autobiographies are filled with ‘I, I, I’, one of the salient aspects of this book is the multitude of times, throughout, that Basset hands the credit and the praise to those around him. He constantly acknowledges the sacrifices, talents and achievements of his widow Nina. He is warm with praise and admiration for the sommeliers who beat him in competitions. Of his Wine MBA he writes, ‘The supply chain management module was a real nightmare for me … If my team had relied solely on my input, we would have had some atrocious results and the fictitious winery we were managing would have gone bust. Thankfully, Marc Torterat, our team leader, was very savvy, resulting in us obtaining some excellent marks.’

In particular, it is striking to realise that although we think of titles such as Best Sommelier in the World to be the achievement of a single man or woman, it in fact takes a team of people. Scratch that. An army of people. The lengths Basset went to over the years in order to achieve his titles were extraordinary. He hired the services of a magician, a TV actor, a business coach, a voice coach, World Memory Champions (yes, such a title exists), a PR consultant, MWs and sommeliers. He bought books on sports psychology, drawing from snooker champions and football managers. He created a team with a manager and two mentors who worked with him on training schedules, strategies, tastings, drills, feedback and techniques. Nina, the sommeliers who worked for him and friends in the trade put in hundreds – if not thousands – of hours to set up blind tastings, drills and tests. Companies sponsored him to help with the (significant) costs of alcohol, equipment, outfits, travel and accommodation. Head sommeliers at Michelin-starred restaurants let him come and practise working during their services to prepare him for competition pressure.

It’s not only the people. It’s time. Basset achieved Best Sommelier in the World on his sixth attempt. Each attempt involved months and months of training – for the final two attempts, he put in at least a year of preparation. That required not only an astonishing level of commitment from Basset, but also from his family. Basset constantly draws parallels with Olympic-athlete training and he in no way exaggerates. You don’t achieve all those letters after your name without making it the work of a lifetime. Basset himself wrote, ‘Looking back, there was a price to pay for my competitive streak … But nothing great happens without a cost.’ It’s a sobering lesson for ambitious newcomers.

Perhaps more sobering is the toll exacted by the stress of the hospitality business. While Basset never had to face the kind of abuse and discrimination meted out to female sommeliers such as Victoria James (above) or Black sommeliers such as Tinashe Nyamudoka, nevertheless it was no joyride. Whether the global economic crash of 2008, a run of bad chefs, ugly court battles with unscrupulous businessmen and Brexit, all faced by the Bassets, or a pandemic, faced by the global hospitality industry today, this book brings home just what a tough game it is.

Needless to say, none of this – not even the last two chapters when he is diagnosed with cancer – is written with a shred of self-pity or resentment. Perhaps this is simply the character of a man who seemed to have gratitude woven into his DNA. Or perhaps looking down the barrel of the cancer gun gives you another perspective on life. Either way, reading the afterword, by Nina Basset, brought tears to my eyes. ‘Cancer was the one challenge that even he could not beat.’

One final note. Throughout this book is a golden thread. It’s Nina Basset. Quite apart from the adoration and praise her husband heaps on her throughout the book, it is crystal clear that she is a woman of immense, and immensely understated, talent and ability. It was Nina who ran the businesses and managed everything from staff, budgets, front of house, marketing and decorating to lawyers and parenting while Gerard focused on his Olympian achievements. It was Nina who picked him up when he was depressed, disconsolate or devastated. It was Nina who nursed him. It was Nina who said, every single time, knowing the sacrifice, ‘Go for it.’