It may be popularly believed that wine writers like me are sent Bordeaux first growths all the time but this is very far from the truth. So when, in early July, I opened a box of wine to find a bottle of Ch Lafite 2019 in it it was quite an occasion. Especially since it had been sent not from Bordeaux but from a producer of Chinese wine.

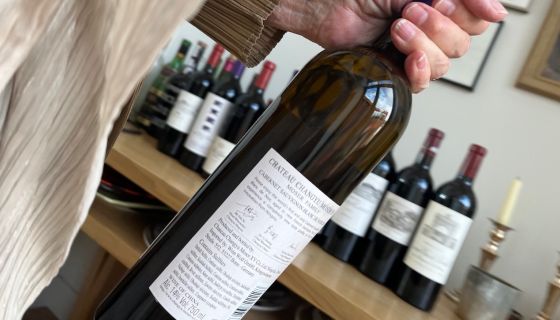

Austrian Lenz Moser has a joint venture in the Chinese province of Ningxia with the biggest Chinese wine company, Changyu, called Chateau Changyu Moser XV, the Roman numerals a reference to the 15 generations of winemaking Mosers since 1610. He wanted me to taste his top Chinese wines against what he saw as the competition, top Cabernets from around the world. So he had put together bottles of four smart red bordeaux – the Lafite plus Figeac 2018, Léoville Las Cases 2017 and Pontet-Canet 2017 – plus the 2019 vintage of Napa Valley’s famous Opus One, to be compared with the first two vintages, 2016 and 2019, of his top Chinese wine and the extremely expensive Cabernets made, respectively, by Lafite and LVMH in China: Long Dai and Ao Yun.

See below for the average retail prices per bottle cited by the leading price-comparison site, Wine-Searcher. I have only just looked these prices up and find them quite amazing – especially those for the Chinese wines, which have no real track record. And it’s interesting to see confirmation that top Napa Valley Cabernets now cost more than many of Bordeaux’s most famous wines. No wonder the Bordeaux merchants are currently so keen to add them to their portfolios. (Tom Parker MW will be reporting in the next few weeks on this year’s Beyond Bordeaux tasting organised in London by CVBG.)

I assume that Moser didn’t have to pay for his own wines – and perhaps Changyu stumped up the cost of this two-person tasting (though I did suggest to Moser that he invite other tasters). But I can’t help totting up the total cost, excluding the bottles of the Changyu Moser wine that is called, presumably because the name resonates in China, Purple Air Comes from the East (PACE for short). It comes to £2,264, of which the two Lafite-owned wines make up more than half. (The holding company Domaines Barons de Rothschild is not famous in the wine world for undercharging.) I already anticipate horrified reactions in the Comments section below this article on ft.com to the shocking waste involved in opening these bottles for only two tasters.

But once we’d agreed on a date for this comparative tasting, it was wine quality rather than price that interested me and I strongly suggested that the wines should be served blind. So Moser poured them into identical glasses numbered one to nine and only he knew what order he had served them, although I did know which wines were involved.

It was quite clear that one wine was head and shoulders above the rest. Yes, Ch Lafite 2019, the one Bordeaux first growth in the line-up (and by far the most expensive wine). And it seemed to me there was one wine that was definitely disappointing, rather crude and overdone. With a high, 15% alcohol, Moser’s PACE 2019 is the second vintage of this ambitious Chinese Cabernet. But the first vintage of it, PACE 2016, I thought was excellent – I even thought it might be Figeac, one of my favourite red bordeaux, until I tasted the real thing further along the line-up. Moser, who had to make up the 2019 blend based on wine samples couriered to Austria because of the pandemic, is convinced that it will eventually rival the 2016. I’m not so sure.

I confused Ao Yun with Long Dai, but they are hardly my everyday drinking and my chief takeaway was that, PACE 2016 apart, these Chinese wines, some of the very best that the country has produced so far, did stand out as being less subtle than the rest. But then they are made from relatively young vines, in terrain that is new to the grapevine, by people without long experience of it.

One thing that stuck in my mind from Moser’s comments on his Ningxia wines is that, because they see so little water, the Cabernet grapes there are absolutely tiny so there is no shortage of flavour from the skins. The vines grow in desert conditions – irrigated drip by drip from the Yellow River. A further disadvantage of Ningxia (though not of the regions that yield Ao Yun and Long Dai) is that winters are so cold that vines have to be painstakingly buried every autumn to protect them from fatal freeze. But a major advantage, and the reason so much wine is made in Ningxia, is that the provincial government has identified wine production as the saviour of what was a rather impoverished land and does everything to support it. See The vinification of Ningxia.

Moser is now involved in joint wine ventures all over the world. He explained to me by email after the tasting. ‘I had to reinvent myself again during COVID as my China business was dead for two years (only on-trade at the time).’ So today he makes Grüner Veltliners with Markus Huber in Austria, dry ‘Mad Moser’ Furmints with a wine producer in the Hungarian town of Mad and, most recently, a really interesting white wine from Portugal’s great Arinto grape grown near Lisbon with winemaker Pedro Ribeiro. Moser and Ribeiro claim to be selling this wine in ‘the lightest [bottle] in the premium field globally at 360 g’.

The 67-year-old explained his diversification thus: ‘These whites are great to counterbalance the more red-wine-leaning Chinese centrepiece of what I do. China is and will remain our lighthouse project as we value the chance and our relationship with the people of Changyu (Chairman Zhou top down) for 18(!) years. And when do you get the chance to shape Chinese exports, being the first to do so …?’

His Austrian wines are branded New Chapter, as well they might be since Lenz Moser is the name of the important Austrian wine company sold by his parents in 1987 to an Austrian consortium, and is also, as wine students know, the name of a vine-training system invented by his grandfather. The current Lenz Moser left the family company in 1997 to work for the late Robert Mondavi in California, whom he describes as ‘my springboard to the global fine-wine business – eternally grateful’.

It’s interesting to wonder what the congenitally expansionist traveller Robert Mondavi would have made of the Chinese wine market that took off like a rocket in the first decade of this century but has shrivelled recently. Will it ever recover from anti-corruption measures (‘gifting’ fancy wine was endemic at one stage), a trade war with Australia, once a prime source of imported wine, and an exceptionally severe lockdown?

I think it will be a while before China is a major wine exporter.

China v the wine world

Average retail prices. Wines are listed in the order they were served blind.

Ao Yun 2016 Yunnan 14.5% £231

Ch Léoville Las Cases 2017 St-Julien 13% £185

Purple Air Comes from the East 2016 Ningxia 14% £127

Ch Pontet-Canet 2017 Pauillac 13% £103

Ch Lafite 2019 Pauillac 13% £739

Ch Figeac 2018 St-Émilion 14.5% £255

Purple Air Comes from the East 2019 Ningxia 15% £153

Opus One 2019 Napa Valley 13.5% £320

Long Dai 2019 Shandong 14.5% £431

Tasting notes, scores and suggested drink dates in Lenz Moser’s big Chinese trial. International stockists on Wine-Searcher.com.