After excoriating scoring here several months ago, let the spittoon of scorn now pour forth on its tasting-note bedfellow, the language of wine.

Words are claimed to be the definitive keys to unlocking a wine’s secrets. We know this because wine writers claim it at great volume, in the same way that winemakers claim to have unique terroir and estate agents claim to sell 'refurbishment opportunities'.

Believing such proclamations requires at least as much self-delusion as it does conviction, because cursory scrutiny reveals that wine words are frequently ineffective, that soil types vary little the world over and that refurbishment opportunity is simply a euphemism for condemned hovel. Which, coincidentally, is the natural habitat of many a wine writer.

Anyway, part of the problem is that so many words, like so many wines, are wide open to interpretation. Instead of debunking the manifold mysteries of wine, they become upbunked. Where they should bring elucidation, only is brung delucidation.

First into the dock is 'minerality', the most prolific offender of the vinous lexicon. In an attempt to decode its meaning, much has been written on the subject of late, but the definitive judgement comes from wine’s holy book, The Oxford Companion To Wine, 4th edition. 'Imprecise tasting term and elusive wine characteristic [...] It is easier to say what it is not than what it is.' Here endeth the lesson; thanks be to Jancis and Julia.

'Freshness' is equally slippery, a noun that gets applied to any wine of any style as a vague and generic catch-all compliment rather than an accurate description. Ostensibly related to acidity, it can mean anything from ‘this Shiraz has too much added tartaric’ to ‘this Chardonnay was picked underripe’.

Yet the proliferation of freshness and similar terms might simply reflect the fact that there are no better alternatives, one might argue. Especially if one has just checked and found that one has used the word freshness in no fewer than 227 tasting notes and 38 articles. Cough.

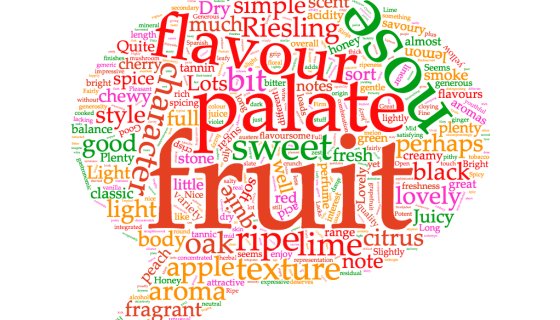

Flavour descriptors have long been ripe for mocking, especially after the irrepressible verbiage of Oz Clarke (pictured above) and Jilly Goolden appeared on primetime BBC programming throughout the 1980s and 1990s. For a time, tasting notes turned into a posh greengrocer’s stocktake, the more exotic and obscure the fruit the better. Whereas these days there seems to be an emergent minimalist trend, whereby terms like ‘citrus’ or ‘black fruits’ are all that is proffered to describe flavour.

Then there are those bespoke descriptors that make little or no sense to those outside wine’s inner circle. Length. Legs. Reductive. Core and rim. Nor is it just the wine world: the perfume industry has a term which apparently means the degree to which a perfume's fragrance lingers in the air when worn – ‘sillage’. As Miss Hoover might say in The Simpsons, it’s a perfectly cromulent word.

Now we cross-fade into the unfined and unfiltered world of jargon. There’s a fine line between evocative adjectives for mainstream consumers and dense jargon for niche professionals. Or indeed niche jargon for dense professionals.

Jargon is designed to distinguish the knows from the know-nots. It’s like remembering that you should always pass port to the left and never cut the nose of a cheese; such etiquette is simply a way for the enlightened to feel clever while making the uninformed look stupid, although it just as often has the opposite effect.

Wine jargon serves the same purpose. Using the right terms – especially abbreviated versions – is a shortcut way of boasting your credibility among peers. Which is why conversations between wine people often resembles communication between spies.

'There was nine months bâtonnage in 100% new French. I did a short pre-ferm cold soak on the Pinot. It had partial destem, whole bunch, with no inoculation and daily punch downs. The microfilm is encrypted with the master key.'

So is there a better way of communicating about wine than words, with their imprecise or unclear meanings? It doesn't seem likely. Words may be imperfect, but until something better comes along, they are perfectly cromulent.

Wordcloud image thanks to wordclouds.com