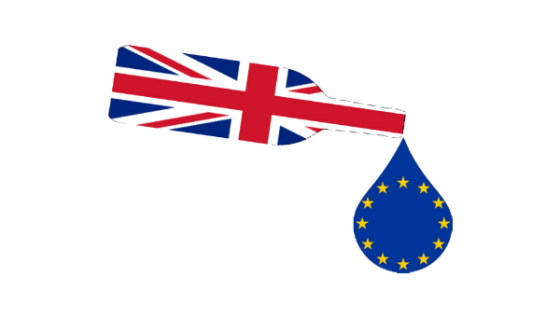

Back in March, in What would Brexit mean for wine lovers?, I set out what I thought might happen in the event that the UK referendum resulted in the UK voting to leave the European Union (EU). The conclusion I came to at that point was that nobody knows what will happen in the event of a Brexit, but it is likely that the price of wine from the EU would increase for UK wine lovers. Now that the Leave vote has won and the UK is set to exit the EU, my conclusion appears to be right.

As I write this article on the evening of Monday 27 June, nobody I have spoken to since the referendum knows what is going to happen. In the two days of trading since the referendum result, the financial markets have reacted in a way that, among other things, is likely to make EU wine significantly more expensive in the UK.

Whether you are popping champagne corks celebrating victory or drowning your sorrows in defeat, my guess is you are probably interested in how Brexit will affect the cost of your wine. So I will try to unpick what I can at this early stage.

Currency markets

The euro/sterling rate as markets closed on the day of the referendum was 0.77. As markets closed yesterday, Monday 27June, the rate was 0.83, so the pound has weakened by about 8%. This alone has increased the cost of EU wine in the UK by 8%.

I spoke to RBC Capital Markets to get their views on sterling’s performance since the referendum. They see the current slump as relatively small compared with other historical slumps. ‘During eight independent sterling price slumps we identify over the last 40 years, the pound has on average fallen 18% against the euro and 14% against the US dollar.’

So it may not be as bad as it could have been. However, a recovery does not look likely any time soon. RBC state that ‘slumps have on average lasted 23 weeks before a material bounce, again suggesting markets do not move quickly to equilibrium and there is no reason to suppose this will be the case on this occasion either.’

In the light of last night’s announcement by the ratings agency Standard & Poor’s that they have downgraded the UK’s credit rating from AAA to AA (negative outlook), stating that the referendum result could lead to a ‘deterioration of the UK’s economic performance’, the value of the pound is likely to continue to fall in value, further pushing up the cost of EU wine for Brits.

The weakening in sterling will have been anticipated by many and a number of UK merchants I spoke to had hedged their position in advance of the referendum, but this is likely to soften the blow for only the first few months. If the pound continues to weaken, the reality will kick in once the biscuit tin is empty and the UK trade’s pain will be shared with consumers. [See also this thread on our forum for the possible implications for importers of EU wine into the US – JR]

It’s not just merchants and consumers who are feeling the bite. Winemakers need to make a living too. I spoke to Jane Eyre, a winemaker based in Burgundy, who has just started selling her wines into the UK in the last 12 months. She told me, ‘Prices have been on the rise since 2012 and now we have the UK, a very important market for Burgundy, opting out of Europe. The crash of the pound puts my prices up instantly.’

The UK is a new market for Jane, but producers who have more established relationships with the UK market and are more reliant on it are likely to feel the pinch if their wines become unaffordable.

Andrew Nielsen of Le Grappin commented, ‘being both a French winemaker and importer of our wines into the UK, the Brexit result is a catastrophe. In the long term there is huge uncertainty obviously, but in the short term our UK business could quickly become untenable well before Brexit happens. Burgundy and Beaujolais are already facing the toughest vintage that anyone can remember following vineyard damage from frost and hail, and now poor fruit set and disease pressure from a wet spring. Fruit prices in Burgundy are already double what they were in 2011 and it is hard to see that there won’t be further increases for 2016 as a result. Combined with the poor exchange rate, we can easily see our Burgundy wines being priced out of what the market can bear. Our Beaune Premiers Crus at over £60 on the shelf at our retail partners is well within the realm of possibility. Currency volatility will mean that it would be prudent for us to allocate more of our production to our other importers, keeping more of our revenue in the currency where our costs are denominated. If 1.2 to the euro is the new normal, it is hard to see a way forward for our UK business, and that is before any hurdles put in our way from an actual Brexit. Here in Beaune this week, every person we chat to is sad and horrified by the decision the UK has made and we, in turn, have no answer for them.'

What will the divorce look like?

In an effort to get a better understanding of the potential outcomes of a Brexit agreement, I called Jean-Claude Piris, who used to be the legal advisor to the EU and advised on the likes of the Maastricht, Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon treaties.

He suggested that ‘any arrangements that are agreed between the EU and the UK following Brexit would be worse than the conditions for trade than they have now'. He said that the arrangements which are in place between the EU and both Switzerland and Norway, which have both been referred to as possible examples of how the UK deal could work, would not be acceptable to the EU. Indeed the EU is seeking to change the terms of the treaties with both Switzerland and Norway because they do not work as currently drafted. Instead, he referred to a ‘free-trade agreement model', which does not mean ‘free’ trade, but a limited series of trade arrangements between the EU and a so-called ‘third state’.

He referred to the EU arrangement agreed with Canada in February 2016, the ‘Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between the EU and Canada’ (known as CETA) as the type of arrangement that could be put in place with the UK. The following is an excerpt from the CETA summary document, which states ‘wines and spirits are the major export item of the EU agricultural and food industry to Canada. Tariff elimination is complemented by the removal of other trade barriers, including several behind-the-border barriers that have prevented the EU from substantially improving its performance in the Canadian market.’

Therefore it is likely that, owing to the importance of the UK for EU wine-producing countries, an agreement would be reached which would make EU wine competitive in the UK. The issue is timing.

Piris outlined the devil in the detail of the Lisbon Treaty. The EU cannot negotiate the terms of trade with a third state until it becomes a third state. In the case of the UK, this will not happen until two years after the UK triggers Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty [the necessary mechanism for beginning exit negotiations].

Therefore, technically the two years will be used to determine the legal arrangements for making the split. Arrangements in place for how the EU and the UK will interact with each other after the split would not be negotiated until after the UK becomes a third state. In this scenario it could take up to a decade to agree all of the terms.

In practice the EU would probably allow informal consultations to be conducted during the two-year period before Brexit to allow parallel negotiations to take place, thus speeding up the overall process to maybe seven or eight years. During the period following Brexit until the final trade agreements are in place, the trade tariffs between the EU and UK would revert to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) tariffs, which for wine imports is 32%. So the longer this negotiation goes on, the longer wine lovers will suffer inflated prices for EU wine.

This is made all the more daunting by the fact that as soon as the UK becomes a third state it will also have to renegotiate the terms of trade with all of the other WTO countries as no current agreement exists between them and the UK as a standalone state, only as an EU member state. Therefore, although the UK will be free from the constraints of the EU to trade with non-EU wine-producing countries such as South Africa, Australia and the US, it will have to negotiate the trade tariffs while divorcing the EU.

The return of duty-free?

Before 1999 we Brits enjoyed taking home duty-free fags and booze from our European holidays. Could the return of duty-free help offset the increased cost of wine following the Brexit? Probably not. As part of the EU, UK nationals can fill the boot full of wine in France and take it home without paying any UK duty. You have to buy the wine duty-paid in France of course, but the duty on wine in France is just 2.8 centimes per bottle, compared with £2.08 per bottle in the UK. So it’s practically duty-free already.

If duty-free shopping is re-introduced there will be limits to how much you can import without being charged UK duty, so wine lovers are likely to be worse off overall and the booze cruise will be consigned to history.

Is Brexit an opportunity for English wine?

If the cost of EU wine in the UK is going to increase, an obvious solution for wine lovers is to turn to English wine as an alternative. This creates an obvious opportunity for the English and Welsh wine industry.

Julia Trustram Eve of English Wine Producers has said in response to the referendum result, ‘we face a new chapter in our nation's history and undoubtedly with that will come changes and opportunities. The UK wine industry remains excited and optimistic about its future.’ Richard Balfour-Lynn of Hush Heath was also positive about the prospect of Brits turning to English wine. ‘Leaving the EU is a great opportunity for the English wine industry to reduce duty and encourage more home-grown sales.’

English wine producers are not limiting their market to the domestic sales. Tamara Roberts, CEO of Ridgeview, is still positive about the UK government negotiating a deal with the EU which will allow them to continue to grow international sales. ‘While we felt our business was stronger in the EU, we will now work hard to continue our success with exports and building our brand in an increasingly competitive international market place. We have to hope that the government is capable of negotiating the best possible free-trade agreements.’

Richard Balfour-Lynn also highlighted the opportunities in non-EU markets. ‘Much of our export is to the US and Japan rather than the EU, and so there is unlikely to be a huge impact when it comes to the export of our premium English wines.’

So, it is very early days and things are constantly evolving, with global financial markets changing the picture by the minute. Only time will tell what Brexit will mean for wine lovers but it certainly seems that there will be some short- to medium-term pain for wine lovers before there is any gain. The silver lining is that it gives English wine the opportunity to step out of its niche and establish itself as a real player in the mainstream UK wine market.