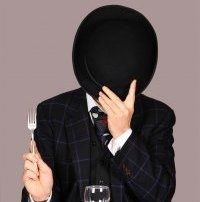

François Simon, France's least recognised but most respected and most feared restaurant critic thanks to weekly columns in Le Figaro, Figaroscope and disguised appearances on the cable channel Paris Première, approached our corner table at Stella Maris in Paris carrying the tools of his trade and displaying singular sartorial élan.

In a black leather shoulder bag were his notebook and pen, several different credit cards and the small video camera he uses to record menus and dishes when he feels he is not being watched.

With his tight, three-piece black velveteen suit and white shirt slightly open at the neck anchored by a broad black and white silk foulard, he gave the impression of a Dickensian dandy, although his thick, tousled hair and constantly surprised expression gives him a puckish air. I will not describe his features in any more detail as he believes, like me, that anonymity is an essential prerequisite for our profession. As the reputed inspiration for Anton Ego, the restaurant critic in the film Ratatouille, he has arguably reached a vast international audience, although the reality is younger, and far less pompous, than his cartoon alter ego.

Simon's standing within France is impeccable. Julien Roucheteau, the talented executive chef at the Hotel Lancaster, described him as 'the tops', as someone whose positive review can promptly fill any restaurant. For Jean-Pierre Tuil, a long-established Parisian PR specialising in food and wine, Simon is the ideal journalist. 'He is unknown, he always pays and he always speaks his own mind', he said. One regular reader, who admires Simon for his elegant use of the French language as well as for his judgement, described him as 'redoutable' or fearsome.

Simon's gentle speech and quiet demeanour initially belied this strong image. But these characteristics, along with his introduction into the charms of French bourgeois food, go back to his childhood at the mouth of the Loire, on France's west coast.

'I'm one of eight children and my father was a barrister. I grew up in a landscape that was light and gentle and the food I was brought up to enjoy mirrored that. It was slow food: veal, chicken, cheese, without spices or pepper. But close to our home was a coffee roaster and as I grew up I began to appreciate these aromas and to realise that to extract the maximum flavour, you have to cook ingredients to their limit', he said. He claims to be able to cook chicken 200 different ways including 'chicken with Coca Cola', which he prepared for the friends at his own wedding party at Juveniles, a favourite wine bar in the 1st arrondissement.

His initial interest in literature, rock music and 'venomous girls' morphed into writing for a provincial newspaper before he moved to Paris to work for Henri Gault and Christian Millau, editors of the Gault Millau restaurant guide, whose influence was profound but unexpected. 'They taught me how to write', Simon said emphatically.

He then exhibited three distinctive features of his approach. Firstly, he pulled out his small video camera to record the menu, a practice he normally only does under cover. But Stella Maris is one of the very few restaurants in which he is known thanks to a long-standing friendship with its Japanese chef/owner, Tateru Yoshino, whom Simon befriended when he first arrived in Paris and subsequently wrote a book about.

Then he declined the wine list, saying that he never drinks at lunchtime. 'It makes me lazy, too gentle and too mellow. I want to keep sharp', he added. The other part of his regime is to keep his body in trim – despite eating out at least 10 times a week in Paris, France or beyond – of cycling between meetings and restaurants.

The arrival of a pre-starter, a small bowl of chestnut soup which we had not requested, allowed me the opportunity to ask Simon whether he objects to this offering as much as I had heard he does.

'This one isn't too bad', he replied, taking a sip, 'given the cold weather, but normally yes. Sometimes it's the chef using up yesterday's ingredients and that obviously I resent. But it's also the principle. I don't want the chef taking control of my meal. When this happens, I feel dispossessed.'

Simon then set out his principles. Most chefs, he believes, exhibit a very high stress level but it is not his role to stroke their ego, support their anxiety or pander to their ambition. 'I don't want a chef in my stomach. But when chefs are gentle with themselves, the customer will always sleep well', he added.

Hence the need for anonymity, although he fears this may not last much longer. After 10 years in his job, Simon is known to France's top chefs but he always books under a pseudonym and often eats alone, something which he confesses to enjoy. 'If and when the chef arrives at my table, then emotion arrives and the analysis is over. Customers don't normally have this relationship, so why should I?' he explained. The resulting detachment certainly allows him to be waspish in print.

This independence naturally extends to paying his bills. Simon believes that he is one of the few remaining restaurant critics in France to do so and that 80% of restaurant reviews in France is now underwritten by the restaurants. The majority of the writing has just become too polite, he added. 'It's a terrible thing for the French press.'

Before turning to the most exciting aspects of his job, Simon turned his ire on Michelin inspectors and French sommeliers, both of whom are simply too stuck in their ways, in his opinion. The ratings of the former say to chefs that they should rest on their laurels, become an institution, solid and uninspiring while the latter are often just too narrow-minded and dictatorial. Simon is no believer in the much-vaunted science of food and wine matching. These are a matter of personal opinion and pleasure. 'I always fight with sommeliers because I like my champagne and white wine ice-cold', he confessed.

What gives Simon the ultimate professional pleasure is not to verify those already established, but to discover new chefs. 'There's talent everywhere and what is most exciting for me is to travel round France to unearth it', he said optimistically. 'I was recently in Sens and I had such a disappointing meal in a two star Michelin restaurant, so predictable and boring. Then I went to a small bistro afterwards and it was so good and so inexpensive. Fighting food, lively.'

France's young chefs, and their more experienced counterparts who have not become set in their ways, need Simon's enthusiasm, dedication and energy. He did mention that it is certainly not always fun to be a restaurant critic, that it can be very tiring for the body. Especially, if a country's culinary reputation rests on such slender shoulders.