In 2000, when JR wrote her first article for what was to become this website, the world was a very different place. The euro had just been launched; the Olympics had taken place in Sydney; and Concorde was about to be grounded. In the intervening period, the world’s population has grown by 400 million. Restaurants were very different, too.

In 2000 the only two ways of making a reservation – of communicating with the restaurant – was either by phone or by sending an email. There was no SevenRooms, no OpenTable, no Resy, no Tock. Communication then was much more direct and personal. No third parties were involved and the reservations book was just that, a big book in which reservations were taken in pencil so that they could be erased in case of the (frequent) cancellations. Taking reservations in an extremely busy restaurant is invariably difficult – ‘like dealing with a moving jigsaw puzzle’ was the verdict of a receptionist in a New York restaurant that used to serve, after a busy breakfast and lunch service, up to 300 customers every evening.

But receptionists and those who answer phones cost money, so restaurateurs, initially in New York and London, began not to employ them and from around 2010 some converted their restaurants entirely to non-booking establishments, exactly as they were when they first appeared on the streets of Paris in the 18th century. The restaurant was open for business but on the basis of first-come, first-served, a policy that applied in the evening but rarely at lunchtime. This marked a shift in the balance of power between the restaurateur and the customer in favour of the restaurateur, whose job now included queue management. In London the late but brilliant Russell Norman was the first to apply this policy deliberately, at Polpo. Queuing has been accepted by New York restaurant-goers for a good 15 years.

It produced the biggest and most obvious physical change in restaurants over the last quarter of a century: a queue of customers waiting patiently in line outside the restaurant’s front door regardless of the weather. Presumably because of my age and lack of the necessary patience, I have never queued outside a restaurant myself. For the many diners younger than me, queuing is obviously worth it. Those I have spoken to say that queuing can be fun, that there is the prospect of meeting like-minded people in the queue, and that they do move along. It is a topic discussed at some length by the young food writer Ruby Tandoh in her new book All Consuming (published by Serpent’s Tail, £18.99).

Restaurants in 2000 were still predominantly the white-linen, deferential businesses that were to undergo a startling transformation in 2002 when Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli was first acknowledged as the ‘best restaurant in the world’, and even more so when in May 2003 the late Joël Robuchon opened his first L’Atelier du Robuchon in a hotel on the left bank in Paris.

If you look up L’Atelier on Wikipedia, it defines this restaurant as ‘A new, more relaxed format for fine dining, featuring an open kitchen and counter seating with stools’. The key words are ‘more relaxed’, ‘open kitchen’, ‘fine dining’ and ‘counter seating’ which contain the majority of the significant physical differences in restaurants that have taken place between 2000 and 2025.

Restaurants today are no longer the domain of white linen they once were. With the exception of Clarke’s in Kensington, London, shown above and founded in 1984 by Sally Clarke, linen tablecloths have virtually disappeared, their sound-dampening qualities taken over by acoustic panels and acoustic-friendly paint (in the hands of thoughtful restaurateurs). Instead, many interiors are a mass of wooden tables topped, if you are lucky, with a thick fabric napkin. The importance of the linen supplier as the judge of which restaurants were the busiest, which he undoubtedly was when I ran L’Escargot in the 1980s, has definitely declined.

Today the vast majority of restaurants are far more relaxed than they were pre-2000. There has been a levelling up in the relationship between the customer, far more savvy and informed than in the past, and those working in restaurants. The days of the snooty waiter, of the de haut en bas approach from the receptionist, have all but disappeared.

The second transformation, only visible once you have entered the main part of the restaurant, is that today increasingly all the chefs are no longer confined to a windowless basement but instead visible in an open kitchen. This is a fundamental change and the ability to fit a kitchen in alongside the customers can today determine whether a modern restaurateur or chef will take premises or not. Having to run dishes up in an electric dumbwaiter, or for waiting staff to physically carry them up stairs on trays, is highly undesirable today.

The open kitchen, off to the left of Stefan Johnson’s view of the interior of the original St John restaurant above, is possibly the biggest single transformation of this quarter-century. It obviously makes far better use of small spaces. It reduces costs for the restaurateur by reducing the number of waiting staff and making the job of the runner, the person responsible for taking or overseeing the transfer of plates from the kitchen to the correct table, redundant. It also makes the whole restaurant experience more interesting. I remember once sitting next to an old friend with no connection to the business in a restaurant with an open kitchen when a van parked outside and the driver brought in four legs of Mangalitsa pork, bred in Wales, and delivered them straight into the kitchen. This prompted my friend to say, ‘that’s what I like about this business – it’s so open. I may never be a better person but I leave a restaurant today a slightly better cook, invariably having learnt something’.

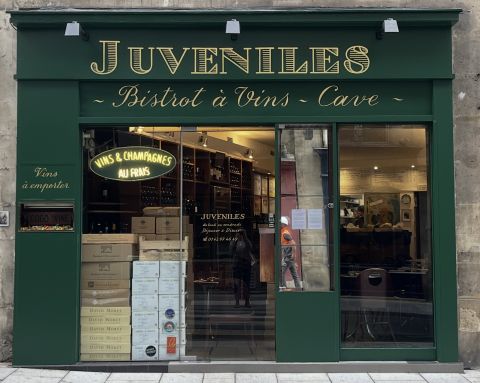

I have always disliked the expression ‘fine dining’ but I have to admit that I cannot think of anything better. And the emergence of the open kitchen has very rarely led to any drop in the overall quality of the cooking on offer. In fact, I would go as far as to say that the quality of cooking in restaurants in 2025 is considerably higher than it was in 2000, from menus that are invariably briefer if more original and definitely broader in their appeal. Today there are considerably stronger influences on the menu – and often the wine list – from South America, the Middle East, Asia, the Indian subcontinent and Africa, at all quality levels – although French cuisine still flourishes at Juveniles in Paris, founded in 1987 by Tim Johnston, an early example of a model common today: wine bar/wine shop/restaurant.

Restaurateurs seem finally to have taken notice of what British restaurant writers have long wished for and installed counter or bar seating, long the norm in the US, as standard. In fact, in many cases counter seating is something of an exaggerated term to use for the small spaces converted into tabletops, areas which would have been ignored in 2000 but are welcomed today.

That is of course when the restaurant you have chosen is open to serve you, which is no longer what was the normal practice of opening for both lunch and dinner, Monday to Saturday. This is the most recent physical change in restaurants over the last quarter of a century: that many restaurateurs now choose to open only for the more profitable services. This is a direct consequence of reopening post Brexit and post COVID. A worldwide shortage of staff, especially European staff in the UK, led many restaurateurs to open gradually and when they realised that their future lay in closing on Mondays and Tuesdays, this situation crystallised. Honore Comfort of the California Wine Institute, a Healdsburg resident, told me recently that it is virtually impossible to find a good restaurant open on a Tuesday in Sonoma. Many others have decided to close on Monday but stay open on the busier and, therefore, more profitable Sunday.

Another significant change has been the emergence of the breakfast menu in many restaurants. I have long claimed that entertaining at breakfast is the least expensive option due to the absence of any heavily marked-up alcohol. The American habit of breakfast meetings seems to have caught on in the UK, with the prevalence of Caravan, Ottolenghi, Granger & Co and many other restaurants open from as early as 7 am.

Customers may use restaurants for longer periods of time in 2025 than they did in 2000 but I wonder whether in a world of the internet and one in which most of us use third-party booking services to secure reservations, the close ties that used to exist between the restaurant and their customers have been stretched, perhaps broken. In my days as a restaurateur, it was always interesting, and often fun, to take a booking on the phone from someone from Scotland, the north of England, Paris or occasionally in the late afternoon from the US and to discover the reason for their visit. Sadly, that personal connection has been lost today.

Come back next Sunday for part 2.