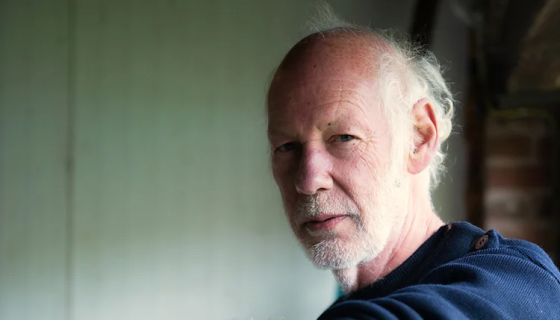

Peter Hall, one of the greatest, if not the greatest, British winemaker to have lived so far, has sadly died aged 82 peacefully at his home, Breaky Bottom in Sussex. His four children, Tom, Kate, Emily and Toby, and his widow Christine announced the news, having been at his bedside to the end, saying ‘his true character did not falter for a single moment, and we will love him dearly for evermore’.

His grandfather on his mother’s side (M Alex Mercier) ran a French restaurant in Soho before the First World War. At an early age his ‘Grandpère’ taught him that while it was important to respect a wine based on its label, the ultimate judgement is for the taster based on what is in the glass:

‘He would say to look at the label, acknowledge where it comes from and learn about the producer. He would then pour wine for us kids, clap his hands, and say: “Anyway, children, remember it’s only fermented grape juice. You are the taster; you have looked at the label, you have saluted it, and now over to you. What do you think? No matter what a wine is or where it is from, it is only fermented grape juice.”

‘Whether it cost £2 or £200, if it is really good, you say fair enough you have paid XX for this wine and you give it two thumbs up … or 18.5 points if you’re Jancis [Robinson]. She’s 100% focused on the glass, and I approve of that.’

After graduating from Newcastle University in agriculture, his first job was as a shepherd on Iford Farms, encompassing what is now Breaky Bottom and leased to him for raising pigs. He met and married the estate owner’s daughter (Di Robinson) and they had four children born between 1970 and 1974. His first vines were paid for by profits from the pigs, and he planted them in the birth year of their youngest child, Toby.

Today the vineyard still has nine rows of the original 1974 planting of Seyval Blanc, which are one of the only parcels in England with recognised old-vine status. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir were planted to replace Müller-Thurgau after the millennium, and now account for 40% of the vineyard (the other 60% being Seyval).

When asked about the differences, he said: ‘Chalk and cheese. They are different wines. Seyval can do very well here. The Chardonnay and Pinot were planted by taking up my Müller-Thurgau. There was a proper rising of Champagne varieties in England. I don’t regret that because it makes a really good blend.’

In the last 16 years, most vintages he produced two cuvées, one exclusively from Seyval Blanc and the other a blend of the Champagne varieties. In 2018, however, there was abundance of fruit and, uniquely from this vintage, he bottled the Chardonnay and Pinot Noir separately as Blanc de Blanc and Blanc Noir cuvées. He always named each of his cuvées after someone who had been important in his life.

Earlier this year, before the English-wine tasting organised by Libération Tardive on 1 April, I asked him why his wines aged so well, what did he do to enable longevity. He responded, ‘It is a wonderful mystery, I don’t know, I dance a jig to the question, but I cannot give an absolute answer. But storing of wines over a decade or more is pretty difficult … it needs to be temperature controlled. It’s difficult with limited funds to build anything perfect for storing that long.’

The 2025 harvest is almost ready and will be picked next weekend by a dedicated team of friends and family. The wines made from this harvest will of course be called Cuvée Peter Inglis Hall.

Photo by Genevieve Stevenson, courtesy of Breaky Bottom.