Who would have thought that worms would play such a crucial role in the champagne producers' current public relations campaign?

All over the world, champagne, the most ostentatious drink of all, is of course in the vanguard of consumer spending casualties. Even the British, champagne's most faithful friends, put the brakes on imports in the second half of last year, causing them to fall back to 2005 levels. So for the first time for many years, the Champenois need to sell themselves a little rather than graciously allocate their wares.

Accordingly, last week's big annual generic champagne tasting, as usual held in the Banqueting House, just up the road from Downing Street, where for all we know Messrs Darling and Brown were simultaneously drawing up plans for crippling increases in excise duty on sparkling wines, was for the first time preceded by a press briefing on the current state of play in Champagne.

Of all the world's wine regions, Champagne has until very recently been notoriously unengaged with the worldwide movement towards more sustainable practices in vineyard and winery. It has some of the highest yields and the lowest proportion of organic vineyards of any French wine region with only about 150 hectares certified organic out of a total of 34,000. (Champagne Fleury is truly exceptional: a biodynamic champagne exported to the US and UK.) Champagne's vineyards have traditionally been scattered with Paris's distinctly unorganic-looking waste. In some vineyards in the Champagne region, moss has even been spotted, a sure sign that the soil below is too dead to sustain organic growth.

But the Champenois have at last realised that a more long-term approach is necessary, and at last week's briefing we were treated to a presentation of the region's slowly developing environmental credentials. Much was made of their collective efforts to recycle winery waste products – currently at 75% recycled with the aim of 100% by 2020. Pesticide use has apparently fallen by 35% in the last 10 years and they promise they will try to reduce it by 50% by 2018.

But the pièce de resistance of the presentation was the triumphal living proof of the microbial health of the soils in Champagne, which, we were told, boast one tonne of worms per hectare, 'which is very high', Champagne's head of environmental matters Arnaud Descôtes assured us. 'Are they alive?' muttered my specialist champagne writer colleague Tom Stevenson. A few minutes later my Blackberry buzzed with 'Who counted the worms anyway?' from Monty Waldin, biodynamics enthusiast and star of the Channel 4 series Château Monty, to whom I sent news of the Champenois statistic. 'You only get worms in soils if the soils are not compacted (not the case in Champagne), are full of microbial life (ie animal manure compost, not waste from Paris), and are aerated regularly either by plough or cover crops.'

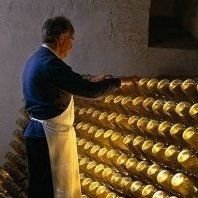

It was telling that the previous day, Champagne Bollinger, always in the vanguard of quality initiatives, had held a similar briefing to present its sustainable credentials to assembled press and customers. Their viticulturist was able to say that they had reduced their herbicide use by half in the last three years and aim to eliminate them entirely by next year. Even more significantly perhaps, they have used no fertiliser at all for four years. There was pointedly no mention of the Champagne region's enthusiastic application of fertilisers at the generic presentation the next day, although there is clearly a general realisation that grassing the vineyards between the rows of vines will help soak up any toxic residues from years of agrochemical use and help restore microbial health to the soils. Bollinger have already grassed over a third of their own extensive vineyards, and the images illustrating the generic presentation, perhaps unsurprisingly, showed beautifully verdant vineyards rather than those littered with multicoloured urban waste.

But perhaps the most riveting statistics presented by Bollinger concerned the extent to which the composition of champagne grapes has changed in the last 20 years, mainly thanks to climate change. Average yields have increased by a jaw-dropping 50% since 1989, while over the same period, average acid levels have fallen by about a quarter and grape musts are almost a whole degree more potent. This must have had quite an effect on the resulting wines, even though, with its second fermentation in bottle, champagne is a more elaborated wine than most. The extent to which less fastidious producers now add acid to musts in warm years such as 2003 and 2005 must have increased enormously – even if some may have been tempted to deacidify musts after the cool recent vintages of 2007 and 2008. (Both operations are legal.)

It was against this semi-industrial backdrop that I scoured the Banqueting House in search of real excitement and integrity in a champagne bottle. (Speaking of champagne bottles, some of them surely qualify as some of the least tasteful designs on the market. Gold and swirls proliferate.) It was impossible to taste all 200 wines on show, so I concentrated first on fashionable rosés to see whether they had improved since I last tasted them systematically five years ago, and then on superior bottlings such as vintage-dated champagnes from the most reputable producers.

The overall quality of the pink champagnes was rather better than in March 2004, although they were extremely varied in quality, style and even colour. Champagnes such as Pommery's Springtime Rosé and Charles Heidsieck's Rosé Réserve need the word Rosé on the label to qualify as pinks at all, so pale are they. Alfred Gratien's Cuvée Paradis Rosé and Demoiselle, La Parisienne Rosé from Vranken are typical of the sort of very pale salmon colour pioneered by Krug when they launched a rosé in 1983 – although in the meantime Krug have deepened the colour of their offering considerably. (The fact that this wine, retailing at more than £200 a bottle, was being poured at the Banqueting House presumably indicates that the pink champagne bubble has burst.) At the other end of the spectrum, Piper-Heidsieck's Rosé Sauvage looks like strawberry pop and tastes, not unpleasantly, only one step away from Sparkling Shiraz.

The vintage champagnes were, usefully, shown at a central table in vintage order. It is always difficult to judge the youngest vintage at this tasting because grander producers tend to give their vintage champagnes extended bottle age, so the first few examples are generally weaker than the average, but the 2004s looked pretty promising.The 2003s, made from the exceptionally early, heatwave vintage, on the other hand, are extreme champagnes. Very ripe, rather simple, blustering wines which seem to have aged very fast, these can be fun so long as they are enjoyed on their own terms. I would drink them long before the 2004s and the well-structured, complex 2002s. The 1999s are good for current drinking too, while the best 1998s are just coming round.

I did not compare the regular non vintage blends that act as principal ambassadors for each champagne brand because I believe such wines should be served blind for this exercise to be really effective, so dominatingly influential is each brand's image, even for us professionals.

FAVOURITE CHAMPAGNES

Of wines tasted last week (there was no Dom Pérignon or Roederer Cristal, for example), I gave all the pinks below a score of at least 17 points out of 20 and the vintage champagnes at least 17.5.

PINK

Agrapart, Premier Cru Les Demoiselles

Bollinger

Gardet, Rosé Charles Gardet 2002

Krug

Louis Roederer 2004

VINTAGE

Gimmonet, Brut Gastronome 2004*

Moutard, Six Cépages 2004

Agrapart, Minéral 2003*

Veuve Clicquot 2002*

Billecart-Salmon, Cuvée Nicolas François Billecart 2000

Bollinger 2000

Charles Heidsieck 2000

Pierre Moncuit, Blanc de Blancs 2000*

Henri Giraud, Fûts de Chêne 1999

Gosset, Grand Millésime 1999

Bruno Paillard, Assemblage 1999

Pol Roger 1999

Philipponnat, Clos des Goisses 1998

Pol Roger, Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill 1998

* denotes a score of 17.5. The rest scored at least 18