Those of us who write about restaurants are always subject to one of these questions: Did they know you were coming? Were you treated particularly well? Did the kitchen do something special just for your table? I don’t believe that wine writers are ever similarly accused. Those who write about films and the theatre are treated differently with special (free) tickets and screening times, while those whose metier it is to review books are well known and treated accordingly.

On the basis of what must be our tenth visit to The Sportsman at Seasalter on the north Kent coast recently, I can provide an emphatic ‘no’. The reservation was made in the name of our friends whom we had met many years ago and now live close by. We were shown to a lovely table in the room off to the right, a table which offered views across the bleak Kentish marshland to Whitstable. And when JR asked whether the owner Stephen Harris was in that day, she was greeted with another immediate ‘no’.

I first wrote about The Sportsman in 2012. It has always been an exciting restaurant to visit for numerous reasons: the relaxed service; the meticulous cooking of predominantly local ingredients; the history – if you close your eyes and then open them, you can well imagine that you are in a Dickens novel on a coach and horses en route to London and that you have stopped at a local inn. That is before you have walked off lunch – or increased your appetite with a preprandial walk along the seafront between Seasalter and Whitstable.

So, everything was as it should be on this visit. Neither Stephen nor Emma, his partner, were there. Peter, his brother, was in his particular place behind the bar wearing a green anorak and his usual smile. What was it about this visit that made it so special?

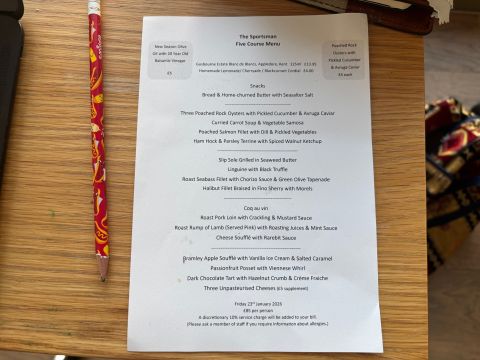

The answer was the menu, pictured above. When our waitress approached our table she asked politely whether we would like to choose from the three-course menu (£45 per person) or the five-course menu at £85 per person. We, naturally abstemious(!), were on the point of choosing the former when our friends chimed in with, ‘the five-course menu please, then we can order the slip soles’ (shown below). So that was the end of that, I am delighted to report.

The menu, as I have written before, is every restaurant’s calling card. It is the chef’s statement of intent: you have arrived and we are here to entertain you, but the menu is there to generate enough profit for the restaurant to thrive.

It is vitally important that chefs do not leave themselves open to the accusation that ‘we left feeling hungry’ but equally importantly they must ensure that their kitchen generates enough gross profit. For the past few years, the cost of most foods has been rising substantially. And this is most obvious in the biggest ingredient of any restaurant bill which is your main course.

The FT carried a headline on 27 January – ‘UK food price inflation rises to its highest in two years’ – citing price rises for meat, fish and fruit. But the biggest increase for restaurants has been that of the dairy products used copiously by restaurants. Then there has been the enormous increase in beef prices since the global demand for steaks has been phenomenal. I recall my meal at Updown, also in Kent, in April 2025 where their dish of a one-kilo Angus steak ‘flew’ out of the kitchen despite a price tag of £150.

Like numerous chefs who offer a multi-course, fixed-price menu, Harris and his head chef, Dan Flavell (‘the same as it has been for the past 20 years’, according to Harris) – use all their techniques and skills in transforming what is available. First up was a series of snacks: miniature goujons of fish, using leftovers; an appealing lamb kofta; and delightful parmesan biscuits. These, together with three kinds of homemade bread and home-churned butter with Seasalter salt, were almost enough to satisfy me!

Harris has been making his own butter since 2004 and his bread is pretty special, too. (Londoners can enjoy the same at Noble Rot restaurants where Harris is consultant.) The quality of bread made in restaurants today has to be the highest it has ever been. It is an easy and immediate test of any restaurant as it’s invariably their first offering and one that makes a long and often lasting impression. This and any snacks are filling, too.

The choice of first courses included a soup, a fillet of salmon, a ham hock terrine, and three poached rock oysters with pickled cucumber and Avruga caviar. I chose the terrine which was very good but I should have joined the others who chose the beautifully presented and sauced oysters and ate them with relish.

I did not make the same mistake on the next course, ordering the slip sole with seaweed butter with almost undue haste. This is a fish and a cooking technique that Harris has almost made his own. The fish is caught locally; the cooking of it in seaweed is a technique he learned on a trip to Japan. When he came home he realised that there was little difference between the seaweed he found locally and that of Japan.

All this was before the main course, the course that, in this style of menu, shows the biggest change from the past, because today it is invariably somewhat smaller than it used to be. Because we could already have eaten two fillets of different fish, snacks and some bread, there is no need for a massive plate of protein – enough to hide the pattern on the plate as they used to say in the north of England. We don’t need it; we don’t want it; and the kitchen cannot afford it.

So, here the choice does not include beef at all – although it often features on a menu nowadays but with a supplement. Instead there were three other meats – a cockerel, a pork loin and a rump of lamb (among the least expensive cuts) – and all served in sensible portions as well as a vegetarian option of what looked like a fabulous cheese soufflé with Welsh rarebit sauce. I really enjoyed my coq au vin (a dish, shown above, that I will always order in a restaurant) but this was two inexpensive pieces (a thigh and half a leg) with plenty of lardons, mushrooms and onions all covered in an unctuous sauce. The local lamb was also two slices of the meat with plenty of sweet roasting juices, broccoli and fresh mint sauce to enjoy with superior potato purée and a little dollop of Jerusalem artichoke purée.

No restaurant, certainly not one as worthy of a Michelin star as The Sportsman, allows the dessert section to pass without taking full opportunity of allowing the pastry section to shine, which it does via a combination of the straightforward, the obvious and the complicated. There was a Bramley apple soufflé (above) in which the acidity of the apple contrasted with the richness of the vanilla ice cream, and an old-fashioned, comforting passionfruit posset with a home-made Viennese whirl that was as light as air. But best of all was the surprise beforehand of a miniature crème caramel under a glistening caramel sauce (below) that had me almost licking my plate clean. I ignored the plate of macaroons that were served with a bill of £105 per person including an excellent bottle of Godello 2023 Louro do Bolo from Rafael Palacios for £49.95.

We left completely satisfied, only keen to return.

The Sportsman Faversham Road, Seasalter, Whitstable, Kent CT5 4BP; tel: +44 (0)1227 273370

Photo at top courtesy The Sportsman; all others by author.

Every Sunday, Nick writes about restaurants. To stay abreast of his reviews, sign up for our weekly newsletter.