Jancis writes This coming 6 March, for the first time in many years, I will not be sending birthday wishes to Australian Richard Smart, the world’s best-known international viticulturist. He died while receiving palliative care in a home near Melbourne on 2 July, having waited until his son Jeremy and granddaughter Isla, one of four grandchildren, had arrived from Canada. Also in the room were his daughter Rachel Cooper and first wife Bernice.

He had suffered from mouth, tongue and throat cancer four times since the 1980s but until relatively recently managed to carry on his glorious career, unbowed by its effects on his speech and palate. He knew that contact with alcohol often plays a part in this particular cancer and towards the end of his life was a fervid campaigner for more widely disseminated information about the demon drink, chiding particularly us wine writers.

An entirely original thinker, Smart, whom I really must call Richard, mounted many campaigns in an utterly fearless fashion and this against alcohol was just one of them.

At more or less the time he died, I was reminiscing in London about the 1988 Cool Climate Symposium he organised with great aplomb in Auckland with Alan Brady, a pioneer of Central Otago wine production. Richard wanted to show at the event the world’s northernmost (from the UK), easternmost (from Gisborne), southernmost (from Central Otago) and westernmost (from Hawaii) wines. Brady, now making Wild Irishman Pinots, had brought with him the sole remaining half-bottle of that 1987 Central Otago Rhine Riesling made from the blended produce of the four earliest grape-growers in the region.

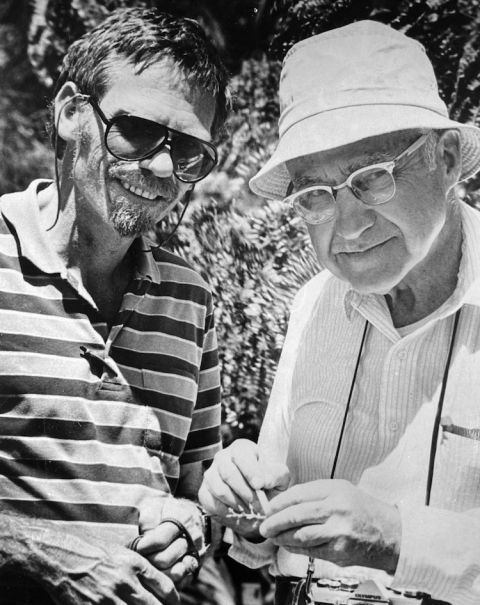

Richard was born in New South Wales in 1945 and graduated from Sydney University with honours in agricultural science. An MSc from Macquarie University followed and he then moved to Cornell in New York state where he studied under Professor Nelson Shaulis, who remained one of his heroes. They are shown together below.

Richard spent the late 1970s in the Barossa Valley where he had a position at the leading wine school of the time, Roseworthy College. In 1981 he moved to New Zealand where he had an extraordinary and thoroughly beneficial effect on the country’s nascent wine industry through his work at Ruakura and Te Kauwhata research stations. Vines there were exceptionally vigorous and grapes struggled to ripen fully. Reds in particular were marked by unacceptably high levels of pyrazines. Developing the work of Shaulis, who had shown in the 1960s that canopy management, exposing leaves and grapes to dappled sunshine, could be the key to improving both yield and quality, he transformed New Zealand vines and therefore wines.

In today’s era of global warming, considerable modifications to this approach have been needed but in the last century Richard’s canopy-management techniques were a godsend for many vine-growers. The book Richard wrote with Mike Robinson in 1991, Sunlight into Wine: A handbook of winegrape canopy management, has become a viticultural classic.

Meanwhile, in conjunction with John Dyson, who had a vineyard in the Hudson Valley and would go on to own a substantial share of Williams Selyem winery in the Russian River Valley, Richard developed the Smart–Dyson vine-training system, which was trialled in 1992 at Dyson’s ranch in Gilroy, California. The system has since been widely adopted worldwide and was particularly popular in South Africa, where Richard was awarded a DSc in agriculture by Stellenbosch University in 1995.

By 1990 he had formed his own independent – very independent – viticultural consultancy and would go on to advise vine-growers all over the world. Throughout this career he claimed 300 clients in 40 different countries, as well as conducting canopy-management workshops, leading technically serious vineyard tours and writing extensively for technical journals. His last article for JancisRobinson.com was What price terroir in an era of climate change?

Between 1990 and 2002 he was deeply involved with a project for producers Cassegrain near Port Macquarie, well north of the Hunter Valley, in conjunction with Australia’s national science agency, the CSIRO. Characteristically, he didn’t necessarily follow conventional wisdom and promoted several unusual grape varieties to combat the humid climate there.

He always took the broadest view of things and was one of the leading voices calling (early) for the mitigation of climate-change effects in wine. He sounded the alarm for the predations of the glassy-winged sharpshooter in California and the extent of damage caused by vine trunk diseases, which he described as ‘worse than phylloxera’, and grapevine yellows in Europe.

After his work for Cassegrain there followed a period when he was based in Tasmania (though he was frequently on a plane). He played a part in the development of the Tasmanian wine industry from 2002 until 2008 when he moved to Cornwall, England, and spread his knowledge and expertise in some English vineyards, including research into growing grapes under cloches.

But by 2019 his cancer was becoming intrusive and he moved to be close to his daughter near Melbourne. She sent these two pictures of her father. About the one at the top of this article, in which he’s shown with John Ellis of Hanging Rock Vineyard in Victoria, she wrote, ‘This is a photo of Dad at his last vineyard visit in February this year. He was so excited and determined to do this work despite our worries for his health and the summer heat. But, he packed up his PEG feeding gear and off he went!’

I knew him best as the viticultural editor of all five editions of The Oxford Companion to Wine. One of my deepest regrets is that with the first edition, having managed somehow to come up with the 800,000 words that made up the meat of the book, I paid scant attention to the title page, which mentioned neither him nor the oenology editor, Professor Dinsmoor Webb of UC Davis, California. They had to content themselves with leading the acknowledgments and heading up the list of contributors. I don’t think Richard ever really forgave me.

Julia, lead editor of the most recent edition of The Oxford Companion, in which Richard was fully credited on a title page, is best-placed to describe what it was like to collaborate with this uniquely well-informed viticulturist.

Julia adds Working with Richard on three editions of The Oxford Companion to Wine involved a good deal of wrangling, via countless emails and the occasional phone call. His voice was increasingly affected by the various surgeries he had had but I learnt to tune in and this made our exchanges more personal if no less feisty. As Jancis noted, he had strong opinions on matters close to his heart but we always came to an agreement, to the benefit of the book. It is difficult to exaggerate the commitment and the amount of time and energy Richard put into a work he was extremely proud of despite the poor financial reward that this sort of book brought. He really didn’t want anyone else to take on his mantle. His viticultural knowledge was as broad as it was deep and when he didn’t have an answer to my questions, he generously put me in touch with his contacts around the world.

His passions were not confined to viticulture. When I first met him, at the International Cool Climate Symposium in Brighton in 2016, he was very keen to promote a technique he had devised with his colleague Angela Sparrow to improve the extraction of tannins, colour and flavour from Pinot Noir skins: ACE (accentuated cut edges), and he did a considerable amount of research into wine’s carbon footprint, arguing for, among other things, carbon capture during fermentation.

We stayed in touch after the publication of the 5th edition of The Companion in 2023 and he loved to send me his most recent articles, especially those on the risks for wine professionals of wine tasting/consumption but also his proposals to help wine regions recover after a surplus, an opinion piece published in the Australia and New Zealand Wine and Viticulture Journal in 2024. He always wanted to find solutions.

Even in January this year he was working as much as he was able on a collaborative paper about canopy design and sunlight interception, the subject that first brought him into the viticultural spotlight. His last message to me was in March, when he was struggling with what he described as ‘brain fog’:

‘It is a terrible experience, I cannot break out of a cycle. I am waiting for sunlight. I am sure that will come.’

A memorial will be held in Australia on Thursday 17 July at 1:30pm AEST at Federation Village, 21-24 Box Forest Road, Glenroy. It will therefore start at 4.30am Thursday in the UK, 8.30pm Wednesday in California. Register to attend in person here, where a link to the livestream has now been published.