What is the future of the wine book? Or rather, whither wine book publishers? Life in the online age is tough for most publishers, and wine writers seem increasingly to be taking the initiative.

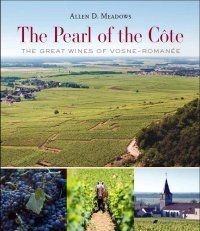

American finance executive turned burgundy guru Allen Meadows, aka Burghound, has just published his first book, himself. Well, not exactly himself. In charge of just about everything except the 180,000 words in the handsome, fully illustrated 350-page monograph on the wines of Vosne-Romanée, Pearl of the Côte, was Erica Meadows (email address mrsburghound@aol.com). What she had to do was 'put together the entire team – and cover all the costs – from several artists, photographers (including taking one up in a helicopter for specific aerial views), mapmakers, book designers, copy editors, printing, computer programming for shopping cart and sales, indexing, book production manager, storage facilities, all fulfilment, etc'.

Or, as Allen puts it, 'self-publishing is not rocket science but it is still impressively complicated because of the huge myriad of details involved in taking a finished manuscript and turning it into a finished book. Then, even when you have a professional product, the marketing and fulfilment challenges are ultimately what make the difference between a successful and failed book project.' He says that it was losing editorial control over the book that put him off the traditional publishing route, but selling a $59.99 book with no middlemen must have its own attractions – provided you can find your market. 'No one should go down the self-publishing path thinking that it's easy because it's not', he warns. 'Aspiring self-publishers should think very carefully about this part of the process because even if they have written the best book ever, it can't sell if no one knows about it.'

But the key to the likely considerable commercial success of Pearl of the Côte is that just about every single potential buyer of the book is already mad about burgundy and highly likely to be a visitor, and probably a subscriber, to Meadows' website www.burghound.com already. Thus, the Meadows have a direct route to their customers and owe nothing to retailers or publishers. Indeed, so confident are they of reaching their market themselves, they have not even bothered to have the book listed on Amazon.com.

Another highly qualified author who recently published his first wine book himself, Benjamin Lewin MW, does have What Price Bordeaux? listed on Amazon, perhaps because he does not have a wine-related website through which to sell this admirably thorough treatise on the wines of Bordeaux, which has apparently sold well enough in its first year to turn a profit. 'I do not know whether that would have been achieved in conventional publishing', muses this career scientific publisher with 40 years of experience in publishing and writing academic journals and books. 'I don't really regard what I do as self-publishing', he told me, 'more as running another small publishing house where I happen to be author as well as publisher.

'In my opinion, there are two general problems to conventional publishing. One is the general incompetence of the publishers: all they really know how to do is to publish more books following exactly the same model as in the past. The second is the way the cost of the book becomes enormously inflated by their overhead. Some of that overhead goes to necessary activities, such as editing, design, and so on – but an author can find all those services, at much lower cost. The problem is bad for books done in black/white, but is greatly magnified if you want to do a four-colour book. A specific problem for wine books is that very few publishers indeed know the market, so the expertise they would usually bring to marketing counts for much less. (For What Price Bordeaux? we had offers from conventional publishers, but the twin problems were that the book would be prohibitively expensive and it would take a full year to appear in the market: neither very appealing. It became clear we could simply do better, both as publisher and in providing books more cheaply and more rapidly to readers, by an alternative route.)'

As the founding editor of Cell, the prominent biology journal, and author of several successful science books, recently qualified Benjamin Lewin, just about to publish his second wine book Wine Myths and Reality, is a considerable asset to the community of Masters of Wine, but is also particularly well versed in the business of specialised publishing.

'The big advantage of conventional publishers, and the main problem for anyone who wants to follow an alternative route, is the stranglehold of distribution. This is less powerful than it used to be, partly because there are distributors who will take on books that are self-published or published by small publishers, partly because of the rise of Amazon and other online retailers. But if you want to have your book represented in the big chains, it remains an issue. It can be almost as difficult to get a distributor who will handle the book, assuming you publish it yourself, and get it into the system, as to find a publisher. And most of them do no more than lip service to distribution: they will fulfil orders, but don't market. So you are almost back where you started.

'One problem of distribution, by the way, is that the system has entirely failed to keep up with modern technology. Trade distribution is predicated on the assumption that publishing will be a slow process, lasting several months. But relatively early in this process, you have to send galleys (or their equivalent) to all the large houses, so that they have time to consider the book and make a decision before its nominal publication date on whether they want to carry it. But this timescale goes back to hot metal. We had bound books in less than six weeks after sending PDF files to the printer. We could have published in under three months, but had to slow the whole process to fit the distribution snail scale of six months because if publication preceded the big chains' consideration, they wouldn't take the book.

'New technology has completely solved the problem of publishing books of high quality at reasonable cost. Self-published books still have a poor reputation – and some chains won't touch them – because of poor quality, but this is not necessary. You can get quality editorial and design services, it is almost trivial to produce PDF files to print quality, and fast, effective, quality printing is widely available. Reprinting is no problem, just a matter of telling the printer to run the presses. The most difficult thing is getting good distribution, and related to that, deciding how many to print: too few and you deprive yourself of the market; print too many and of course you risk financial loss.'

His fellow Master of Wine and English wine specialist Stephen Skelton MW reckons he has overcome this problem, by pursuing Lulu's publish on demand route aimed specifically at self publishers. His 170-page, large-format, illustrated book Viticulture costs £3.64 per copy to print and he can buy any number from one upwards at exactly that price plus postage and sell them on to bookshops and vineyards at a trade price.

'If Lulu sell a copy – cover price £16.50 – then they keep 20% of the difference between the cost and the cover price which leaves me with about £10.50.' He has pursued a similar strategy for The UK Vineyards Guide. 'There are no set up costs as you do all the origination, formatting, proof-reading, cover etc yourself. I used a professional book designer (Geoff Green) for the basic template and to do the covers. I have my own ISBN and register it with them. I keep no stock and order them one by one or as per my customers needs. Lulu send them direct to my customers.'

He has sold a total of about 1,500 copies of Viticulture and 1,000 of The UK Vineyards Guide, which has brought him in about £8 a copy. 'This is far more than I would have got from a publisher. Of course it takes time to format everything and get it right and I have used a professional indexer and help with layout and design. POD (Publish On Demand) is great once you get the hang of things. I write everything in MS Word, convert to a PDF and that's it. To change something – a new phone number or a typo just noticed – just requires you to alter the Word file, create a new PDF and download it. All new copies after that are changed.'

If all this sounds to an experienced author like a completely new world, it is hardly surprising. Today there is just one conventional specialist English-language wine-book publisher on each side of the Atlantic: Mitchell Beazley, a subsidiary of Hachette, in London and the University of California Press in Berkeley. I should immediately disclose that Mitchell Beazley publish The World Atlas of Wine, of which I am co-author with Hugh Johnson, and have managed to oversee the translation of the lavishly illustrated most recent, sixth, edition into 13 languages, something that would be difficult for even the most ambitious self-publisher to accomplish. The California publisher meanwhile seems to publish new wine titles at what feels like about one a month, one of the most recent being Been Doon So Long, the highly entertaining, and beautifully produced, collected ramblings of Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon Vineyard.

I hope my old friend Randall will not take it amiss if I suggest that he is a fine example of an author who probably needs the organisational skills of a conventional publisher.