Joseph Rosenfeld writes having recently graduated from university, where I spent my time balancing Saturday morning blind tasting practice with Saturday afternoon rowing training (not something I recommend), I am excited to be starting my career in the wine industry. I am passionate about telling stories through wine and introducing people to new and exciting bottles! Cheers.

An ode to Zibibbo

Like any good wine story, my love affair with Zibibbo began with 2 key ingredients: a knowledgeable sommelier and a trusting audience. What appeared next was a bottle of Marco de Bartoli’s Integer Zibibbo 2007, and a confused look on my face as I tried to work out which of the names on the label might be the grape – always a good sign! My first sip took me right back to Friday night dinners at my Jewish family home and our classic dessert: freshly baked apple crumble with a hint of cinnamon and the knowledge that soon the guests would leave, and I could sleep. The way in which a glass consisting 85% of water can elicit such powerful memories is quite incredible. I set out to learn just what this new grape was and to drink as much of it as I could get my hands on!

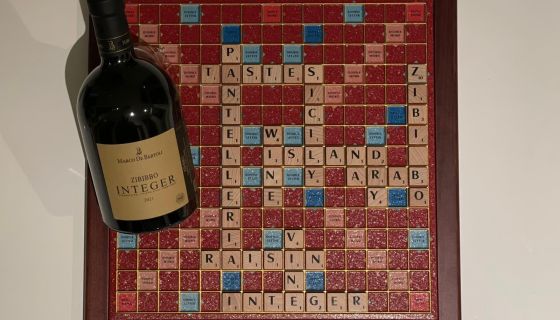

So, what is Zibibbo? Well, it would be a great scrabble word, except, much to my brother’s pleasure, it isn’t in the official dictionary. Aside from that, it is part of the large Muscat family of grapes and is better known by its synonym - Muscat of Alexandria. Originating from ancient Egypt around 5,000 years ago, and rumoured to produce Cleopatra’s favourite wine, it arrived in Sicily around 800BC. Its home became the tiny volcanic island of Pantelleria off the Sicilian coast, which, despite being geographically closer to Tunisia, forms part of Italy. Zibibbo is the local name for the grape variety here, and the name I will use. Recent genetic analysis has suggested the variety is actually a crossing – combining Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains with Heptakilo, a red table grape from Greece.

Conventional winemaking on Pantelleria is challenging with little rain (less than 350mm/year) and famously harsh winds. Battered on either side by the mistral and sirocco winds, the island earned the name Bent el Riahn - meaning daughter of the winds - during its Arab rule from 700 to 1123 AD. In response to these conditions, growers use the vite ad albarello vine training technique, which involves digging a shallow trench in the soil and training the vine as a small bush vine. The trench protects the vine from the salty winds with its walls and acts like a basin to capture what little rain falls. Developed by the Phoenicians and now granted UNESCO World Heritage status, this ancient method of farming is perfectly adapted to the terroir of the island, enabling the successful production of Zibibbo grapes from Pantelleria’s fertile, volcanic soil.

Zibibbo is a powerfully aromatic grape producing wines with a myriad of vibrant flavours. One of my favourite hallmarks of the variety, though, is perhaps the simplest flavour of all: grapes. In my recent role as a cellar door host, where elaborate tasting notes sound more like a shopping list than a wine description, I was frequently asked “When did you add all of those [aromas]?”. It made me realise how those immersed in the wine world sometimes lose touch with consumers. It is because of this that I particularly love the identifiable aroma of table grapes that leaps from the glass of a Zibibbo wine, as it serves to remind us all of the drink’s origin.

But, for those keen to explore, there's more to Zibibbo’s exuberant nose than just grapes. Often characterised by honey and stone fruits, it can also display a hint of savouriness. Think wild thyme and rosemary, and a lick of sea salt from the winds – a kind of Mediterranean cocktail.

Zibibbo’s name is derived from Arabic. Zabib, meaning raisin, explains how this grape survived Arab rule of the island despite wine grapes being of little use to the Muslim population. Its unusual versatility extends from the dried raisin, to the table grape and, most importantly, as far as this essay is concerned, to producing wines that range from the bone-dry expression I first tasted to the intensely sweet Passito di Pantellaria wines. The latter contain up to 200g of residual sugar per litre (twice as much as Coca-Cola) and are what the variety is best known for in this part of the world. Grapes are laid to dry in the Mediterranean heat, creating wines that are decadent, nutty, and perfect for my next apple crumble.

It seems odd to think that the solution to the future of winemaking might be to turn to the past, but this most ancient of grapes has proven to be perfect for our warming climate. Over its long history, Zibibbo has adapted into a resilient grape with distinctive traits, suited to low-intervention sustainable winemaking practice. Its thick skins, ideal for the passito process, can cope with intense sun and extremely dry climates. It is therefore unsurprising that it has now spread its roots; incredible and varying styles of Zibibbo (read: Muscat of Alexandria) wines now hail from South America, Australia, and everywhere in between.

What began as a moment of confusion over a wine label has become a lasting fascination. Zibibbo taught me that wine is not just a beverage but a living history – of migration, resilience, and adaptation. In a world of fast-changing climates and fleeting trends, it's comforting to know that some grapes have been through it all, and are still here to remind us how delicious they can be.

The photo is the author's own. Caption: 'if you get a double letter and triple word tile you could net a healthy 87 points, perhaps a petition to get Zibibbo added to the scrabble dictionary is needed'.