Maura King writes I am a wine enthusiast with a zest for travel. Once I learned that grapes might have parents and grandparents, I wanted to meet the family in far flung places. I get a real kick out of trying autochthonous varieties that do not often leave home and new crosses that might go places. Recently free of work, WSET is filling gaping holes and putting much needed structure on the random bits and pieces of my wine knowledge.

A paean in prose to Probus

What is in a grape name? In 92 AD Emperor Domitian faced with a glut of wine and declining prices issued a wine edict banning the planting of new vineyards. He also ordered the uprooting of vineyards in the provinces. Thereafter the regional ruling classes had to import wine from present day Italy. The plebs did without. Let there be wine! declared warrior Emperor Probus in or about 280 AD when he overturned the earlier ban. Between wars the oenophile Emperor despatched his soldiers to plant grapes.

Emperor Probus was born in Sirmium (present day Sremska Mitrovica) in Serbia. Nearby is Sremski Karlovci, a picture postcard ecclesiastical town on the Danube. There amidst the smells and bells, viticulturists at the Fruit and Wine Institute crossed the high yielding, large berried, Balkan grape Kadarka with small berried, French grape Cabernet Sauvignon. Sremski Karlovci nestles on the edge of the Fruška Gora. The Fruška Gora is a national park peppered with meadows, monasteries, and vineyards. It is not difficult to deduce what inspired the cross. Kadarka was vigorously at home in the loess topsoil of the Fruška Gora but tended to produce a light coloured often light flavoured wine. Cabernet Sauvignon offered the promise of deeper hue, richer flavours, and perhaps French je ne sais quoi. The resulting cultivar, released in 1963, was named Probus in honour of the wine loving emperor, coincidentally himself a scion of humble local stock.

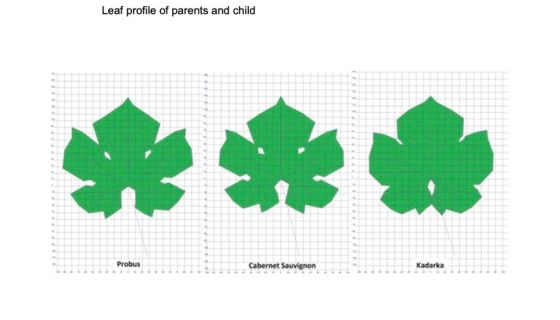

Serbia has cold winters and hot summers. Probus buds late reducing its exposure to late frosts. Like its parents, it is a later ripening variety, making it suitable for a warm climate with a long growing season. The leaves resemble those of Cabernet Sauvignon. Its bunch compactness and berry size are similar to Kadarka. Anthocyanin composition determines the gradation of red colour in wines and aging potential. Probus’s anthocyanin profile is closer to Cabernet Sauvignon than Kardarka even out- performing Cabernet Sauvignon in some respects. In short, Probus took the best both parents had to offer and then raised the bar.

I did not know its history when I first tasted Probus in 2011 in the podrum (cellar) of Vilmos Fehér in Stara Moravica a Hungarian speaking village an hour’s drive from Sremski Karlovci. Stara Moravica is on the Danube plain. Locals claim the alluvial soil is among the top three most fertile agricultural soils in the world vying with the black soil of Ukraine and the corn belt of America. Everywhere nature seemed voluptuously abundant. Vilmos made natural wines in small quantities. Wine making was half hobby for Vilmos. Nonetheless, his tiny cellar was full of trophies won in wine competitions in adjoining countries. We tasted his wines as they came. Each wine was an olfactory immersion in the fecundity of the terroir. We might have tasted 5 wines or 10 wines, I do not recall but I can still vividly remember the moment when an already good wine tasting session became dazzlingly perfect.

That was the instant I first picked up a glass of Probus. Something was revealed in that special Eureka, Newtonian apple drop moment. Probus was a dark, dark red of unfathomable depths. Yet it was the not the intensity of the colour but the seeming weight of the wine that first captivated me. It did not swirl swiftly around the glass the way other wines did. Nor did it loiter the way port did. It appeared to move with deliberate ceremony. It was heavy and unctuous. The upfront aroma was of ripe heading towards jammy dark fruits: black cherry, blackberry even red mulberry. Then there was a secondary terrestrial aroma of rich clay after rain, followed by lingering decadent notes of tobacco and dark chocolate. Tasting Probus was the consummation on the palate of the aromas one after the other, first the fruit so intense it seemed freeze dried, followed by soil, tobacco, chocolate with maybe, just maybe green pepper. The wine was smooth. If that wine had been a fabric, it would be velvet of the highest quality a few tones on the red side of black. But it was not a fabric, it was a liquid imbued with the breath of life. An earthy wine with an unearthly taste.

I have since learned that I had beginner’s luck. Once every 10/15 years when the wine making stars align Probus produces an almost viscous, earthy wine of squid ink shaded opulence. Even at a remove of 14 years if I shut my eyes and concentrate, I can conjure up the visceral pleasure of the 3- stage process from looking to lifting to drinking that was my first glass of Probus.

Any year Probus is a siren call for a lover of robust reds. I have drunk and savoured Vilmos’s wine every year since 2011. It is my favourite fireside Christmas red. The crackle of logs provides a fitting soundscape for its complex, mysterious intensity. I have watched with pleasure as more and more commercial wine makers make Probus, Đurđić, Deurić, Milanović, Zivanović to name but a few. I dive into the depths of Probus to try to re-capture the rapture of first love. It is sometimes tantalisingly close, but elusively never quite there. Yet like a cat on the hearth, Probus makes me blissfully content. The open fire warms my body as Probus warms the cockles of my heart.

Probus honours the emperor who brought wine to the masses. It showcases the skills of viticulturalists whose man-made match produced a heavenly grape. The pungency of Probus wine evokes the soil in which Probus grows while its richness salutes the sun that heats its days. Probus displays features of its parents, but its Balkan élan has a particular oomph of its own. Probus is a swashbuckling grape bearing an old name, boldly forging a new future.

Photo credit: Ivanišević, D et al, Genetika – Belgrade, 2019, 51, 1061–107. The image was provided by the author.