29 October 2019 Burton Anderson, author of so many seminal books on Italian wine, looks back at his favourite wine bottle.

The fiasco, in both the traditional Italian sense of the term for a wine container and the universal expression for a flop, has figured with remarkable frequency in my experiences almost from the start.

The bulbous bottle with the woven straw base came into my life in my late teens in Minnesota when I began my errant career as a wine aficionado with a cheap and cheerful red labelled Chianti. That most distinctive of bottles has held a place in my heart ever since, despite the Tuscan wine establishment’s virtual ban of the fiasco from commercial use that has all but erased a venerable artisan tradition from memory.

As for the fiasco that refers to failure, flubs, fumbles and flops, that connotation has figured so prominently in my adventures and misadventures over the years that at one point I decided to call the not-so-mythical operation that represents my life’s work Fiasco Enterprises. Chuckle if you will, but I happen to take Fiasco Enterprises rather seriously – well, anyway, when I’m sober.

When I settled in Rome in the 1960s and began to discover the world of Italian wine, I focused above all on quintessential Chianti in its iconic flask. I piloted my Fiat 500 up to Siena and Florence to explore the rugged hill country in between, visiting osterie behind grocery stores serving la cucina toscana with local Chianti.

In a book published in 1990, I discussed Chianti of the era as made using the curious method of governo dell’uso toscano, which, in simple terms, consisted of adding dried grapes or their musts to the newly fermented wine to induce a secondary fermentation designed to make the wine mellow and round with a hint of prickle.

As I wrote: ‘When governo worked, whether by accident or design, Chianti expressed pure goodness and a spontaneous joie de vivre that not even the most astute of today’s cellar technicians would be equipped materially or spiritually to achieve. To carry the sentiment further, I adored the fiasco, and saw that two-litre bottle of dark green glass blown by artisans, wrapped with straw by country women and filled with ruby red liquid as the most distinguished of wine containers, the very epitome of rustic elegance. Not only that, the package suited the product perfectly.’

The first fiaschi were apparently made by glassblowers of the Arno and Elsa valleys, where marshland provided straw, reeds or wicker from branches tough enough to be woven around the bottle and last for years. The fiasco was already a common container in Tuscany in the fourteenth century, as attested in numerous documents and works of art depicting straw-covered bottles in various rotund forms.

The traditional Florentine fiasco was often quite large, containing at least two litres and appreciated by prodigious wine drinkers. Larger bulbous containers, holding three, four litres or more, were usually known as damigiani and were bound with wicker or heavy straw from top to bottom. Before corks came to prevail, the customary way of sealing wine in flasks and demijohns was topping it with olive oil, which served as a more or less airtight closure.

Tuscans never threw away a fiasco but kept them because they were decorative and useful for holding not only wine but olive oil and other liquids. They even cook beans in them, if rarely these days; the straw was removed from the flask, which was filled with dried beans, liquid and herbs and nestled amid hot coals to become fagioli al fiasco.

It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that red wines from Chianti in flasks gained much attention beyond Florence, though wines known as Vermiglio and Florence Red were at least as popular on the export market. The ideal way to ship the wine was in small wooden barrels, but as commerce grew and foreigners increasingly insisted on wines in the colourful fiasco, bottlers took to shipping them with olive oil atop and a wicker or paper cap, which could get messy when the train tilted or the boat rocked. Tuscans had ingenious glass siphons for removing the oil, but drinkers abroad with no easy way of extracting it and often drank the wine mixed with blotches of oil.

Chianti’s international breakthrough came in 1860 when Laborel Melini invented the fiasco strapeso of strong tempered glass able to withstand the pressure of cork sealing. Melini at Pontassieve near Florence became a major shipper of Chianti, soon joined by the neighbouring house of Ruffino. Their success inspired blenders and bottlers throughout Tuscany to get in on the act.

In 1872, Barone Bettino Ricasoli, who had served as Italy’s second prime minister, composed a production formula that served as a loosely interpreted model for Chianti for well over a century. Ricasoli made Chianti primarily from Sangiovese, praising its bouquet and ‘vigour of sensations'. He recommended using red Canaiolo grapes to round out the flavour of young Chianti, while noting that white Malvasia in the blend ‘increases the flavour and makes it lighter and more readily suitable for daily use at table'.

In the decades that followed, the formula was diluted with torrents of white from the prolific Trebbiano Toscano as Chianti in fiaschi became the world’s most popular wine. As exports increased, vineyards and cellars burgeoned beyond the core zone of Chianti Classico to sprawl across Tuscany between the Tyrrhenian coast and the Apennines.

Through it all a nucleus of established wine houses and estates based primarily in the area between Chianti Classico and the hills around Florence continued to produce authentic wines of admirable quality. But markets elsewhere in Italy and abroad were overwhelmed by ‘Chianti’ of questionable origin carrying labels that were improvised brands and sold at prices in line with the quality and reliability of the wines.

Over time fiaschi evolved in size and form and also in the patterns and techniques of weaving the straw or wicker around the base, artistic touches that occasionally resulted in masterpieces of rustic craftsmanship. With widespread shipping, flasks diminished in size from roughly two litres to standard 1.5-litre or litre bottles, or often smaller, and ways were found to produce the straw bases mechanically.

To non-Italians the flask became a symbol of Italy and lighthearted wines, serving as a candle holder set atop checkered table cloths of eateries with images of the Colosseum, a smoking Vesuvius or the leaning tower of Pisa on the walls. Among serious wine drinkers, however, the fiasco had become something of a joke and that impression stuck with Chianti even when flasks became as passé as the once de rigueur coupe de Champagne.

Decades of excess had so damaged Chianti’s reputation that by the mid 1970s bottlers in the region agreed that the fiasco, the eternal icon of Chianti, had to go. Today, sadly, only a few heroic diehards bottle Chianti of quality in true fiaschi, though cheap replicas circulate with bases of synthetic straw or dreary plastic.

The term fiasco seems to have derived from the late Latin flasco, though when and why the name for the otherwise esteemed bottle assumed the derogatory connotation expressed as fare fiasco (screw up) is open to speculation. Some have it that it referred to unsuccessful attempts by glassblowers to achieve the requisite bulbous form. Others that it had a theatrical origin in the seventeenth century when the comic actor Domenico Biancolelli picked out objects and spontaneously described them, though his depiction of the fiasco so disappointed the audience that they whistled him off the stage. Fiasco already had a comic correlation in the fourteenth century when Boccaccio, in the Decameron, had Buffalmacco play a trick on Calandrino, giving him two flasks on which he’d painted the glass red up to the neck to make him think they were full of wine.

Whatever the origin, the term fiasco came to signify flop or failure or disaster in many languages, though often in an ironic or satirical sense. It became a common term for business failures, for disappointing theatrical, cinematic and artistic works as well as a bombastic byword in headlines of British tabloids, as in the recent banner headline BREXIT FIASCO!

My experiences with the flop type of fiasco are too numerous to detail, so I’ll limit citations to a few career-related incidents, starting with my decision to leave a prestigious and well-paid position as an editor of the International Herald Tribune in Paris to pursue a dream of writing a best-selling book on Italian wine as a freelance (read unpaid) writer working from a rustic farmhouse (read no phone, no computer, no central heating) in the wilds of Tuscany.

That book, Vino, published in 1980 [and a breakthrough at the time – JR], did not become a bestseller, needless to say, so I considered it a fiasco. Yet it did lead to the publication of numerous other books on Italian wine and food, some of which have been regularly revised and republished under various titles that had accumulated to more than 100 by the turn of the century, when I quit counting.

Although none of those books could be considered literary failures per se, none – not one – has ever satisfied my expectations in terms of copies sold and money earned in royalties or other forms of compensation. And no, I am not one of those authors who consider it a success to simply get a book into print, even though some of those volumes have been published by leading houses in the US, UK, Germany and even Japan. In short, a collective fiasco of colossal proportions.

Beyond that, I’ve started a number of works of literature, intended as books, which I never completed, thus to be considered unrealised flops. These include a couple still in the works that I intend to publish, come hell or high water, though only an incurable optimist, which I am not, would expect them to become commercial successes.

Beyond literary considerations, several times I’ve attempted to make some much needed cash on the side by trying to venture into the forbidden world of wine-related business, while maintaining my pose as an incorruptible writer/journalist. Needless to say, virtually all of those attempts turned into fully fledged flops.

That is why, in the 1980s, I founded Fiasco Enterprises Ltd, described decades later in my blog site Beyond Vino (which, needless to say, flopped) as a non-profit organisation dedicated to the welfare of underdogs, also-rans, has-beens, long shots, lost causes and screw-ups in general.

Fiasco Enterprises? That’s me.

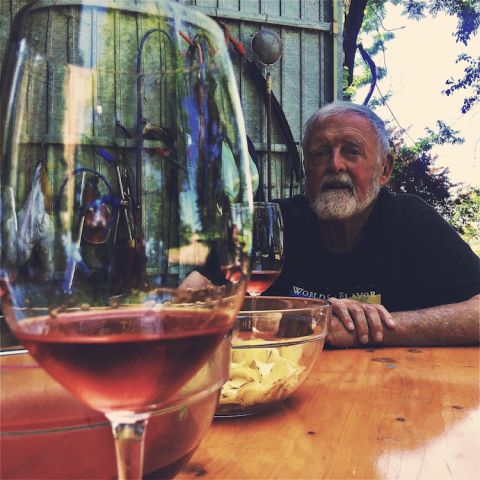

Above, Burton is photographed by his photographer daughter Gaia. He has written an autobiography The Good, the Bad and the Bubbly: Reflections on a Lifetime in Italian Wine, which he is hoping to have published in English.