We tend to think about soil as an inert, static substance, a never-ending abiotic resource at our disposal, to build on, drive on, cover up with paving or tarmac, extract from, exploit and profit from. We’ve mined it, moved it, dumped it, reshaped it, lost it to wind and flood. Soil is something to be washed from our cars, scrubbed off our shoes, wiped with admonishments from the hands and mouths of children, viewed with disgust when it’s on our clothes. ‘Who brought mud in?!’, most of us have probably heard bellowed by an exasperated parent, viewing a trail of footprints in the hallway. ‘Soiled’, even today, is a word associated with shame, disgrace and moral ruin.

The irony is that good, healthy soil (in its natural state) is not only dynamic and teeming with life, and is, together with plants, crucial for life on earth, but it is cleaner than the most well-scrubbed home, and is more effective at maintaining the health of living organisms than the most sophisticated medical science we have access to today. With all respect to the clean freaks and the virtuous, our everyday lives need to be soiled, and richly so.

Research by Deep Life scientists estimates that 70% of earth's microorganisms live in the subsurface and that there is as much, if not more, genetic diversity of life below the surface of the earth as above it. They believe that the biomass of carbon-based life in the darkness of the soil and rocks below us ‘utterly dwarfs’ that of surface life. Not only that, but almost 25% of living plant matter, mostly in the form of roots, is below ground (quite literally holding it together): 67% of living grasses, 47% of shrubs and 22% of trees exist underground. The Natural History Museum website says that ‘one teaspoon of soil can contain more organisms than there are humans on earth’.

Above: nutrient exchanges and communication between a mycorrhizal fungus and plants (Charlotte Roy, Salsero35, Nefronus, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The ecosystems of healthy soils are alive, extremely active, vastly complex and poorly understood. Scientists are only just beginning to get to grips with how vital a role the ‘hidden half of nature’ plays. Forget space exploration; soil science is one of the most exciting, and potentially most important, areas of research in the world today.

It’s important because soils perform life-critical ecosystem services. This is a phrase worth becoming familiar with – we’re all going to see it appearing more and more in the discussion about the future of life on earth. Bluntly speaking, it’s a framework of ‘value context’ created by scientists and environmental communication specialists to explain, in a highly simplified format, why environmental issues matter to a world demanding, ‘What’s in it for me?’. The answer, say the scientists, is that the earth and its components are performing vital and, more importantly, free services for your (human) well-being. So, the message goes, it is important that you value these services, and we request that you, please, Nice Human, don’t screw earth and these services up, because ultimately it will kill you (and we’re not even talking that far into the future).

Ecosystem services are classified into four categories: provisioning, supporting, regulating and cultural. The services that soil provides, for example, include:

- Provisioning – soils provide the wherewithal for plants to grow, which in turn provide us with food, beverages (including wine!), medicine, fabrics, fuel and shelter. Soils themselves directly provide us with shelter (think bricks) and it was from soil that the antibiotic streptomycin was isolated.

- Supporting – soils are the habitat to the earth’s greatest biodiversity, the home for countless species of plants, mammals, insects, fungi, bacteria and other microorganisms. Soil provides structural support for all types of plants from fragile grasses to trees over 100 m tall, as well as to all our own buildings, roads and human infrastructure.

- Regulating – soils cycle the nutrients of life, filter and clean our water, play a role in regulating and cleaning the air we breathe, are the main reservoirs of water for plants and are vital when it comes to flood management. The ecosystem balance of microbial life in soils helps to regulate pests and diseases above ground. Soils are the second-largest reservoir of carbon on the planet – sequestering nearly three times as much carbon as all the plants put together.

- Cultural – soils give us the breathtaking beauty of the Douro Valley, the wide-flung curves of the Hunter Valley, the dramatic Mosel, the lyrical landscape of Tuscany, the rugged volcanic island of Santorini. While we might focus on the grandeur or romance above ground, the intrinsic beauty of so many places is down to the ground beneath our travelling feet.

The agricultural industry, throughout the history of settled humankind, but exponentially since the onset of the ironically named Green Revolution (post Second World War), has had an exploitative relationship with soil. Farmers (not just Big Ag) of all commodities and all over the world have persistently, and more and more intensively, implemented the three most destructive practices: plant-cover removal, ploughing and pollution. All three of these ‘traditional’ agricultural practices basically strip the soil of its capacity to perform these services. Viticulture is guilty of all three.

The wine industry is very proud of its relationship with soil but the truth is, it’s a spurious one. For the main part, the production of wine is often as formulaic as the cultivation of wheat: water + chemicals + plants = profit. Even on a less industrial scale, there is dysfunctionality. We obsess about terroir, mistaking that obsession for love of and respect for vineyard soils. But the truth is that terroir, ie soil type, is irrelevant if that soil is dead, non-functioning, unable to do its real job.

The practice of removing plant cover (with herbicides and ploughing) is basically skinning the earth alive. Plant cover is the planet’s hide. Among so many other ecosystems that plants provide, when it comes to vineyard soils, plant cover is crucial for regulating soil temperature, preventing soil erosion, regulating evaporation and water retention, fixing nitrogen, building essential structure which helps with drainage, nutrient transport and oxygenation. Miguel Torres Maczassek, taking part in the panel discussion of the Regenerative Viticulture Foundation launch, commented on the ‘misinformation’ and ‘stuck ways of thinking’ with regard to the wine industry's preoccupation with getting rid of ‘weeds’, ‘tidy’ vineyards and the fear of ‘competition’ from other plants. He said, with real feeling, ‘Once you start [understanding the importance of cover crops], you cannot go back. Every time you see a naked soil, it will hurt you.’

Ploughing, or tillage as it is also known, for so long considered to be the only alternative to herbicides (and thereby one of the most important tools in the organic toolbox) as well as an essential practice for mixing fertiliser and organic matter into the soil and breaking up surface crusts (which prevent drainage into the soil), is actually one of the most destructive agricultural processes. The irony is that many of the reasons for ploughing are caused by ploughing. Tillage might temporarily break up the soil crust, incorporate fertiliser into the soil, remove weeds, oxygenate the soil and improve drainage, but over time it damages soil structure, causes erosion (especially the loss of precious topsoil), releases a massive amount of carbon into the atmosphere, increases evaporation and presents a huge loss of soil water, oxidises soil nutrients and causes a loss of gaseous soil nutrients, destroys microbial life and causes compaction and crusting. The more the farmer ploughs, the more the farmer needs to plough. It’s called a positive feedback loop in science speak, which is something that amplifies itself, moving further and further away from a state of equilibrium, becoming more and more unstable. It was tillage that created the great Dust Bowl crisis of the 1930s.

In a recent fascinating if disturbing seminar on soil pollution, I listened to soil scientists around the world discussing the desperate state many of our soils are in. Synthetic fertilisers have done untold damage to soils, not to speak of what they are doing to our waterways. We haven’t even begun to understand the extent to which fungicides, pesticides and herbicides are damaging subsurface animal and microbial life, as they are sprayed onto plants and soak into the soil with rain and irrigation. But extensive research has been done and is ongoing on the damage being caused by nitrogen fertilisers; most of it is not bioavailable and therefore is not taken up by plants. Ironically, again (that word irony seems to be cropping up a lot), the practice of feeding our soils is, in fact, polluting them. And in another irony, organic viticulture, with its heavy reliance on copper, is also causing well-documented soil pollution.

I’ve already mentioned compaction, which is basically crushing the natural, beautiful, airway-filled lattice structure of soil. That lattice creates the spaces for healthy, deep root growth, movement of water, nutrient transport, and oxygen for microbial life. Every time a tractor runs through the vineyard, soil is compacted. In wet weather, as disease pressure builds, the tractors run through the vineyards more and more often. Wet soil is more vulnerable to compaction than dry soil. Every time a tractor runs through the vineyard to spray chemicals of any type or to plough, the soil is compacted. Vines can’t dig as deep; water can’t drain as deep. Vines become less resilient to drought, less able to share the limited water and nutrients available in the shallow soils with other plants, more vulnerable to extreme temperature changes.

Jamie Goode moderated the panel discussion at the RVF launch, and in his opening remarks, said that ‘the old way of running vineyards, what we call "conventional", is input-heavy, is based on an old-fashioned idea of ecology, and it’s the idea that we focused on the vine, primarily, as the organism of interest … When I went to vineyards in the mid nineties, the best vineyards had bare soil and it was just the vines in neat rows growing out of the bare soil.’ Miguel Torres commented, in the same discussion, that many local growers still regard vineyards with cover crops as ‘dirty’ vineyards (yet another irony). He added, with a wry smile, ‘Their first question they ask, when they see all the green plants beneath our vines is: have you gone bust?’

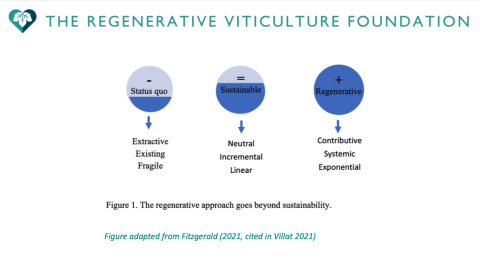

Jessica Villat of the Hoffmann Institute wrote a paper in 2021 entitled, ‘Down to earth: identifying and promoting regenerative viticulture practices for soil and human health’. As her slide below summarises, the status quo is that our relationship with soil is extractive and destructive, soils are fragile and damaged and, should we continue as we are, these soils will no longer be able to support life on earth, let alone the luxury of wine. If all viticulture moved to sustainable practices, the relationship would be merely neutral – taking out of the soil as much as we put in, keeping the planet more or less in its current position where there would continue to be biodiversity loss, degraded soils, broken ecosystems and pollution. With regenerative agriculture, our relationship with soils becomes a contributive one.

Regenerative agriculture mimics nature. Nature doesn’t plough itself up. Nature defaults to plant cover (leave even the most barren earth for long enough, and pioneer species will start to appear). Nature, undisrupted by humans, cycles natural chemicals, pests and diseases with consummate balance.

As Justin Howard-Sneyd MW pointed out at the RVF launch, ‘carrot farmers don’t have so many conferences as grape growers … we in the wine industry lead the conversation on soil’. Mimi Casteel (Oregon winegrower and one of regenerative viticulture’s most active and passionate advocates) described that as she studied for her forest ecology degree at university, it became clear to her that earth’s natural ecosystems ‘were dying from the outside in, because of the privately held agricultural systems around them … If I wanted to participate in maintaining those systems’, she told us, ‘I realised that the front line is agriculture. So that’s why I came back [to the family property in Willamette Valley]. Wine is an agricultural leader, it’s pioneering, it sets visions, it’s an influencer.’ Our responsibility to planet Earth, whatever our relationship to wine, starts with the earth beneath our feet.

If you’re interested to know more, there is a recording of the Regenerative Viticulture Foundation launch, panel discussion and Jancis’s speech, and if you click on the link below, you can access Justin Howard-Sneyd’s presentation on regenerative viticulture.

The images in the article were taken from Justin Howard-Sneyd's presentation or supporting materials.