Valeria Tenison writes my name is Valeria Tenison; I am a wine writer and wine agent based in Bordeaux. I am also an MW Stage 2 Student and a mother of a 4-month-old boy. I am happy to share my ode to Welschriesling, the variety that I discovered thanks to the three musketeers - Igor Lukovic from Serbia, Saša Špiranec from Croatia and Zoltán Győrffy from Hungary. They are the organisers of the GROW du Monde wine competition, dedicated exclusively to one grape variety - Welschriesling. I had the honour to be one of the judges in 2025.

Ode to Welschriesling

When someone asks, What are the international grapes?, most wine lovers will recite the familiar names —Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc. However, I doubt anyone would think of a variety cultivated in at least 15 countries, with around 80 synonyms and a viticultural history spanning centuries and empires.

It answers to many names. Graševina in Croatia. Olaszrizling in Hungary. Laški Rizling in Slovenia. Ryzlink vlašský in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Despite its aliases, Welschriesling remains a single vine with many roots—threads that stitch together a patchwork of countries, cultures, and histories, once joined under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is a grape that quietly threads its way along the Danube and into the glass.

Unlike the glamour varieties—Pinot Noir with its ultimate elegance, Chardonnay with its chameleonic charm—Welschriesling rarely makes headlines. The WSET Diploma textbook describes it as producing “fresh, neutral, unoaked, dry wines, of acceptable to good quality and inexpensive in price.” Not very exciting, right? It has no Burgundian mythos, no Californian cult. Yet in cellars from Fruška Gora to Vienna, it is the white wine of everyday life—served in taverns and family kitchens, cherished in quiet moments and festive ones alike. It is democratic, ubiquitous, and—at its best—extraordinary.

The name itself is a misdirection. “Welsch” (hello, Wales!) comes from a Proto-Germanic root meaning foreigner or Roman, and “Riesling” evokes a noble relation it doesn’t share. Welschriesling is not related to Rhine Riesling. Its closest relative seems to be Elbling, another ancient and underappreciated variety. Its origins remain mysterious. DNA analyses in 2003 revealed that one parent was Coccalona Nera, a nearly extinct Italian grape once widespread across northern Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and southern Germany; the other parent remains unknown. Surprisingly, a variety grown in Spain's Ribera del Guadiana—Borba—was found to be genetically identical, hinting at yet another potential origin. Some even suspect a forgotten nobility: August Wilhelm Reichsfreiherr Babo, an Austrian scientist from Klosterneuburg, once proposed a link with Petit Meslier of Champagne. Yet Dr José Vouillamoz, Swiss biologist and leading grape geneticist, suggests that the most likely origin is the Danube basin, perhaps specifically Croatia, and proposes Graševina as the most appropriate primary name.

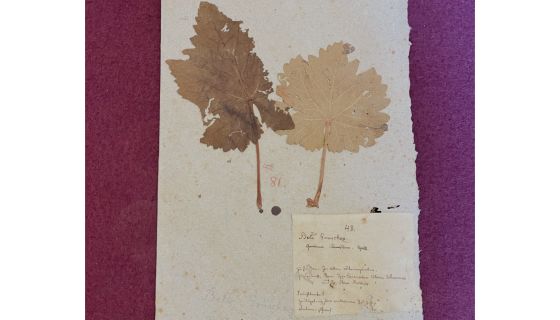

Some speculate the "Welsch" might even refer to Wallachia, a historical region of modern-day Romania, or derive from the Slavic names Graševina or Grasac, evoking “green peas”—a nod to the grape’s plump, pale green berries. In Serbia, it is known as Beli Grasac and was listed in Andrei Volny’s late 18th-century herbarium in Sremski Karlovci—the oldest known written record of the variety. Later renamed Riesling Italico during the Soviet era to benefit from its “noble” foreign name, it was eventually reclaimed under its original identity.

The truth about its origin—lost in the shifting borders and identities of Central Europe—matters less than what it represents today: a grape of place and people. If wine is about terroir, Welschriesling is the perfect guide. It does not impose; it reflects. In Styria, it yields fresh, green-fruited wines with aromas of citrus and green apple, crisp and herbal. In Hungary, especially around Lake Balaton and Csopak, it is austere and mineral. In Croatia, where Graševina is the most widely planted white grape, it can be delicate or richly oaked, depending on the winemaker’s intent. In Austria’s Burgenland, where it is the third most cultivated white variety with 3,338 hectares, Welschriesling reaches its glory in sweet botrytised wines from Lake Neusiedl.

The variety is also widely grown in Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia (where it is the most planted grape by area), Romania, Italy, and even in far-flung places like China (3,000 ha), Brazil, and Canada. But its footprint is shrinking—from 61,200 hectares in 2010 to just 24,384 hectares in 2016, according to Kym Anderson's global grape statistics, placing it 35th in the world by vineyard area. This downward trend is unfortunate as the grape's potential continues to reveal itself in new expressions, including pét-nats, orange wines, single-vineyard bottlings, and elegant sparkling wines. For decades, it was dismissed as a workhorse variety. Still, it is now being reclaimed by winemakers who see beauty in its modesty and adaptability.

And that is what excites me most—not just the grape’s versatility, but its symbolism. Welschriesling is a grape of migration and resilience, of empires and republics, of families who farmed through war and upheaval. It’s a grape that speaks many dialects but shares a common voice. In a time when nationalism often drowns out nuance, Welschriesling is a gentle rebuke: a vine that unites without homogenising and thrives in diversity.

So here’s to Welschriesling—modest but magnificent. A grape that has travelled without boasting, endured without demanding, and bound together cultures that might otherwise have drifted apart. A grape not just of place but of many places. Not just of people, but of many peoples. A grape worth remembering and, perhaps, rediscovering.

Photo: Beli Graschaz from the Sremski Karlovci herbarium.