Emily Johnston Collins writes Emily Johnston Collins is a Sommelier, Wine Director and freelance wine writer. She began her career in wine while living abroad in Italy. She has since returned to California and, more recently, returned to her small hometown of Ojai where she is raising her two boys. Emily is thrilled that Nero d’Avola is beginning to make its way into good vineyards, wineries and restaurants on the California Central Coast- including the restaurant whose wine program she directs.

An ode to Nero d'Avola

I was cold and living in Parma, Italy when I fell in love with Nero d’Avola. Filtering through the market’s collection of cheap, teeth-staining Lambrusco on a characteristically foggy day, I uncovered the fateful bottle. I loved how Nero d’Avola ripened into the perfect, fragrant spice and how it smelled of fruit warmed by the sun. It was the antithesis of Parma’s heavy winter. I had this wine by my side for every dinner party and boozy park picnic over the next year.

I lacked the wine knowledge of my Italian friends, but I made up for it in tenacity. I knew that Nero d’Avola came from Sicily- from reading the label on the bottle- and I deduced from its name that the grape probably originated from somewhere on the island called “Avola.” That was how I came to make a pilgrimage to Avola, dragging along two Americans studying at the University that employed me.

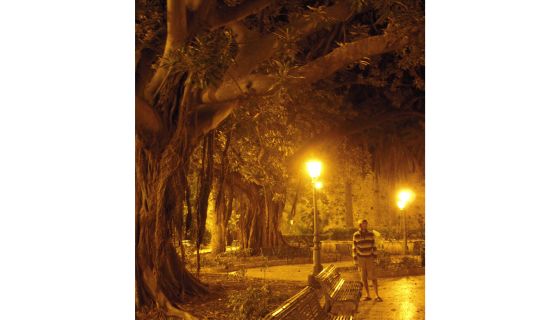

We departed over the holiday weekend of Ognissanti. We flew into Catania, found lodging in lovely Siracusa, and took a bus to Avola- or somewhere near there, because where we landed resembled less of an elegant baroque town on the Ionian coast, and more of an isolated suburb perched in the foothills of the Iblei mountains. It seemed we had missed some pivotal information about the town’s gradual migration towards the sea since antiquity, or more currently, the migration of its residents to the beaches for the weekend.

It was still hot in the last days of October and early November, and the light reflecting off the limestone buildings was glaring and uninterrupted by awnings or any welcome respite from the heat. There were no pedestrians, no cars, no tourists and no visible vineyards. We hiked up a hill and, with equal parts excitement and disappointment, found our pilgrimage’s Finisterre- a communal barrel of Nero d’Avola. It was fitted with a pour spout, and at its feet were splashes of purple-red wine stains. There were recycled, plastic, 1-liter bottles to fill and a box to receive 1 Euro coins. An old lady in a house dress quietly filled a bottle ahead of us. We replicated her actions, bending as if in reverence to reach the spout and splattering our shoes in wine.

We took only a moment’s indulgence of the wine in the plastic bottle. The man who had sold us our return bus tickets- via the limestone canyons of Cavagrande del Cassibile- had recommended we stop to see Avola’s ancient necropolis. So, we traded the bench with a view of Odysseus’s sea for the empty tombs from which the dead had long since moved on.

The stoic island held me at arm’s length for another year before I learned I spoke its language. A professor at the Wine Academy at Gualtiero Marchesi’s Culinary School in Parma was lecturing our class about Sicilian cuisine when he pronounced a word I had previously believed to be familial lexicon. “Milinciani,” he explained, was the Sicilian dialect for “eggplants.” My Italian Great Grandmother used to call them that. With her American accent, it sounded like “milin-johnny,” so I had assumed she coined the term after her son. The lesson continued with the presentation of other familiar dishes like “cuccidati-” the beloved fig-filled cookies that adorned our family’s table at every holiday. I had searched for them unsuccessfully across the Italian peninsula, but had failed to check Sicilian bakeries. Also Sicilian, I learned, were pignolate- the honey-soaked dough spheres shaped into a crown and studded with candied citrus and silver sugar dragées. They seemed to have sprung from a childhood fever dream. A new feverish feeling struck me. I felt hot. My cheeks flushed. When the lecture ended, I lifted up my arms and turned to face the Sicilian student in the class. “My family is Sicilian” I cried. “Ma Dai!” he smiled, catching my arms on his shoulders in a welcoming embrace.

I later learned my Great Grandmother was not, in fact, Sicilian. My family confirmed that she had been born in Naples before immigrating to the US as a young girl. The significant missing detail was that she had been orphaned shortly after her arrival and was taken in by Sicilian immigrants who raised her. In an effort to preserve her family history, she vehemently proclaimed her Campanian heritage, despite speaking in the Sicilian dialect and cooking Sicilian dishes. None of us- perhaps not even her- knew enough to notice the discrepancy.

The magic of sharing a heritage with the grape that launched my wine education had faded. I naturally shifted my interests toward other grapes. When I returned to Sicily, it was for a new love of Nerello Mascalese. Winemaker Federico Curtaz offered to be my guide through the paradise of Mount Etna. He led me through old, gnarled Nerello Mascalese vineyards, around archeological winemaking sites that survived centuries of lava flows, and into the cellars of some of the island’s top winemakers. When I asked him why he had left Piedmont-where he had been Angelo Gaja’s agronomist- to make wine in Sicily, he confided his love for Nero d’Avola. Alongside his wines from Etna, he was preparing to release his first vintage of Nero d’Avola called “Ananke,” after the Ancient Greek personification of destiny. I, too, believe in the inevitability of my bond with Nero d’Avola.

The image, of ficus trees in Siracusa, Sicily, is the author's own.