この記事は、できるだけ早くお届けするためにまずAIで翻訳したものです。今後はAIに教育を行うことでその精度を上げること、それと並行し翻訳者が日本語監修を行った記事と、AI翻訳のみによる和訳記事を明確に分けることで、読者の皆様の利便性を最大限に高めることを目指しています。表現に一部不自然な箇所がある場合があります。ご了承ください。

この記事は、できるだけ早くお届けするためにまずAIで翻訳したものです。今後はAIに教育を行うことでその精度を上げること、それと並行し翻訳者が日本語監修を行った記事と、AI翻訳のみによる和訳記事を明確に分けることで、読者の皆様の利便性を最大限に高めることを目指しています。表現に一部不自然な箇所がある場合があります。ご了承ください。

10月上旬、私は初めてヘレス・デ・ラ・フロンテーラを訪れた。毎朝7時頃になると、リズミカルなアンダルシア・スペイン語の断片が立ち上り、借りていたAirbnbの開け放たれた窓から漂ってくる。熱い油の匂いがその会話に加わると、私は足を床に下ろし、ズボンとシャツを身に着けて通りに出るのだった。

新鮮な農産物が山積みされたテーブルの前を通り過ぎ、大きな屋外キオスクで焼きたてのチュロスを買うために並ぶ長い列に加わる。列の先頭で、熱々のチュロスを4分の1キロ分、油染みが花のように広がった灰色の紙に包まれて手渡される。別のキオスクを営むヘスス(Jesús)は、椅子を引き出し、キスやハグを交わし、今加わった友人たちのためにコーヒーを注文する人々の群れの中から私の目を捉えるやいなや、カフェ・コン・レチェを持ってきてくれるのだった。

夕方になると、この儀式を繰り返すのだが、キオスクの代わりにタバンコを訪れ、チュロスの代わりにヒルダス(酢漬けのアンチョビにマンサニーリャ・オリーブと酢漬けのギンディーリャ・ペッパーを爪楊枝に刺したもの)、チチャロネス、パヨヨチーズ、アトゥン・エンセボジャード(マグロと玉ねぎの煮込みをジャガイモと一緒に供したもの)が並ぶ。コーヒーはクルスカンポ・ラガーのパイントやコパス(グラス)に注がれたシェリーに取って代わられる。笑い声とおしゃべりが、頭上のスピーカーから流れるフラメンコ音楽をかき消していく。

タバンコは樽からシェリーを提供することで有名だ。一般的に少なくとも1種類ずつのフィノ、マンサニーリャ、アモンティリャード、オロロソ、クリーム・シェリーの「デ・ラ・カサ」(ハウス・ワイン)を置いており、これらは地元のボデガから大量に仕入れている。もちろん、ワインの品質はタバンコの品質次第であり、注意を怠ると、シェリーはかなりひどいものになりかねない。

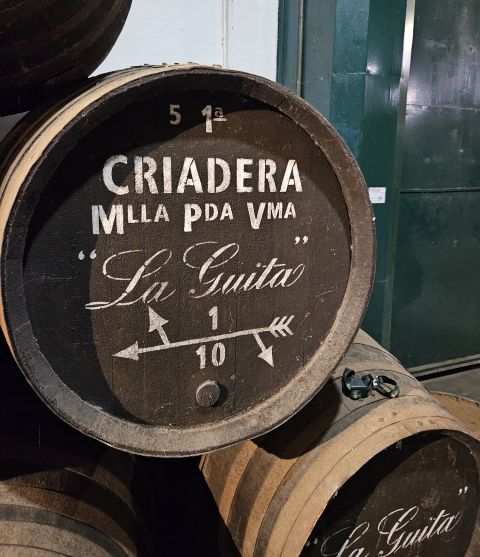

迷った時の解決策は、ハウス・シェリーを飛ばして代わりにラ・ギータを注文することだ。世界で最も売れているマンサニーリャで、ヒルダスを楽しむのに十分なお釣りが残る価格帯なのである。

私が入ったあらゆる店で、食事をしたあらゆるタバンコで、親しみやすいオレンジ色のカプセルが棚から私に手を振り、刺激的なイースト香とパン生地のような香り、柑橘系の酸味、塩味のフィニッシュを持つ辛口のシェリーを約束してくれた。コパス1杯につき0.5ユーロ余計にかかるかもしれないが、決して私を失望させることはなかった。

幸運なことに、私はラ・ギータを訪問することができた。グルーポ・エステベス(バルデスピノ、ボデガス・マルケス・デル・レアル・テソロ、ラ・ギータの所有者)の技術責任者を最近まで務めていたエドゥアルド・オヘダ(Eduardo Ojeda)(写真上)が、ラ・ギータのワインメーカーであるベアトリス・カバジェロ(Beatriz Caballero)(写真下)を紹介してくれた時、私はすぐに彼女に、これほど大規模な生産でどうやって品質を高く保っているのかと尋ねた。

その後に続いたのは、カバジェロがスペイン語で答え、オヘダが翻訳し、私が5語に1回は説明を求めるというやり取りだった。しかし、それは主に以下のことに要約される…

- ラ・ギータは、サンルーカル・デ・バラメダ産のブドウのみを使用する唯一の大量生産マンサニーリャ・ブランドである。

分かっている。あなたは「でもマンサニーリャは法的にサンルーカルで造ることが義務付けられている」と考えているだろう。サンルーカルで造ることが義務付けられているのだ。しかしブドウはヘレスのどこからでも調達できる。サンルーカルのより冷涼で湿潤な気候がフロール(フィノとマンサニーリャの美味しい軽やかさと明るさを生み出す酵母 - タラがその仕組みをここで説明している)の成長に影響するという考えを受け入れるなら、その気候がブドウの樹の成長とブドウの化学成分にも影響し、最終的により軽やかでよりクリスプなワインをもたらすと信じないのは愚かなことだろう。 - ブドウはほぼ全て有名なミラフローレス(Miraflores)のパゴから調達されている。

約325ヘクタール(約800エーカー)に広がるミラフローレスは、少なくとも18世紀からブドウが植えられており、生産されるブドウの品質で名高い。ここのアルバリサはサンルーカルの大部分よりも純度が高く、ブドウ畑は海に面してなだらかに上向きに傾斜しており、大西洋の風がブドウの樹の間を流れることを可能にしている。 - 酒精強化に使用される96%のグレープ・スピリッツは、ヘレスDOのパロミノ・ブドウから蒸留されている。

ほとんどのブランドは汎用のグレープ・スピリッツ(実際にはその大部分がラ・マンチャ産)を使用している。グルーポ・エステベスは何年も前から、酒精強化用スピリッツの香りの品質がワインの香りの品質と一致するよう、格下げされたパロミノ・ブドウを地元の蒸留所に送り始めた。 - ラ・ギータは大部分のマンサニーリャよりも長く樽で熟成される。

マンサニーリャは平均3年間樽で熟成されるが、ラ・ギータは4.5年間樽で熟成され、ワインにより鋭いフロール・キャラクターを与えている。 - ラ・ギータは年に6回(そう、6回だ!)ボトリングされる。

マンサニーリャは一度ボトリングされると、可能な限り新鮮なうちに消費するのが最良だ。これを確実にするため、ラ・ギータは年に6回ボトリングする。これは2つのことを意味する:マンサニーリャは継続的に新しいワインが供給されてフロール酵母を強く活力のある状態に保ち、ワインにより多くのフロール・キャラクターを与える;そしてあなたの近くの棚にあるボトルは可能な限り新鮮である(小売業者が在庫を回転させていることが前提だが)。

他のワイン・ライターからも聞いたことがあるだろうが、良いシェリーは魔法だ。そしてまた、どういうわけか、不可解にも、奇跡的に、安価でもある。しかし、それをそのまま維持したいなら、もっと多く飲むのが最善だろう。オヘダは農業産業が直面する課題について遠慮なく語った。彼の心配をチュロスの観点で表現すると…

チュロス用の小麦はスペインで、時にはアンダルシアで栽培されている。しかし、小麦産業は人々のグルテン消費量減少により、ワイン産業と同様の低迷を見せている。チュロスを揚げる油は以前はアンダルシアで栽培されたヒマワリ油だったが、今ではほとんどがウクライナからの輸入品だ。塩はカディス塩田から来ていたが、今では安い塩が中国から輸入されている。チュロスにつける砂糖は伝統的にアンダルシアで栽培されたテンサイから作られていた。テンサイ糖の最後のメーカーは2026年に閉鎖される。使わなければ、失うのだ。

オヘダは、1973年にはヘレスに約23,000ヘクタール(約57,000エーカー)のブドウ畑があったことを思い出させてくれた。今日では約6,500ヘクタール(約16,000エーカー)だ。これはワイン愛好家だけの問題ではない。ワイン産業の上に成り立っているヘレスのチュロス・キオスク、カフェ・コン・レチェ、タバンコを愛するすべての人の問題なのだ。シェリーがヘレスを築き、シェリーがヘレスを生かし続けるのである。だから、次に買い物に出かけたり、バーに座ってオリーブやアーモンドと一緒にコパスを飲みたいと思った時は、シェリーを注文してほしい。そして何を探しているか分からない時は、棚からあなたに手を振っているオレンジ色のカプセルをいつでも頼りにできる。

メンバーはテイスティング・ノート・データベースでより多くのシェリーの推奨品を見つけることができる。