この記事は、できるだけ早くお届けするためにまずAIで翻訳したものです。今後はAIに教育を行うことでその精度を上げること、それと並行し翻訳者が日本語監修を行った記事と、AI翻訳のみによる和訳記事を明確に分けることで、読者の皆様の利便性を最大限に高めることを目指しています。表現に一部不自然な箇所がある場合があります。ご了承ください。

ロバート・スタニエ(Robert Stanier)について ロバート・スタニエ牧師は、ロンドン南西部のサービトンで牧師を務めている。副業として、サン・シニアンのすぐ南にある小さなワイン産地コート・ド・トング(Cotes de Thongue)のワインに特化したウェブサイト「cotesdethonguewines.co.uk」の執筆・更新を行っている。妻と3人の子供がいるが、誰もワインには興味を示していない。

アラモン(Aramon) – 忘れ去られるべき品種か?

アラモンほど愛されないブドウ品種があっただろうか。オックスフォード・ワイン・コンパニオンの項目の最初の一文は、この品種が存在したことへの後悔を表しているに過ぎない。「アラモンは幸いにもフランスのブドウ栽培史の遺物である」と。実際、今日では絶滅に近い状態にあるため、この記事を読んでいる人の大半は一杯たりとも飲んだことがないだろう。そこで私は弁護の論陣を張りたい。たとえそれが、もはや決して存在することのない世界への旅を意味するとしても。

まず少し歴史を振り返ろう。19世紀、アラモンはラングドックを支配していた。植えられた1本の樹から驚異的な量のワインを生産できることで珍重されていたのだ。色は期待外れなほど薄く、アルコール度数も自然に低かったが、フランス北部の工場労働者たちがそれを大量消費していた時代には、さほど問題ではなかった。重要だったのは生産性だった。20世紀が進むにつれて消費者が色やアルコール度数の不足について文句を言うようになっても、生産者は北アフリカから輸入される色の濃いワインとブレンドして、問題なく販売することができた。

この均衡は1962年にアルジェリアが独立するまで続いた。この植民地支配の転覆がもたらした意図せぬ結果として、アラモンはもはや安価な北アフリカ産ワインとブレンドして誤魔化すことができなくなり、その本質が露呈した。ほぼ他のどんなワインと比べても、色の薄い弱々しい赤ワインだったのだ。

1960年代から70年代にかけてミディ地方全体で経済が全面的に破綻する中、ブドウ栽培者は次々とアラモンの樹を引き抜き、カベルネ(Cabernet)、メルロ(Merlot)、グルナッシュ(Grenache)、シラー(Syrah)、カリニャン(Carignan)、実際アラモン以外なら何でもという具合に植え替えていった。

数十年をかけて、ラングドックは徐々にワイン経済を再建し、まず安価だが頑丈な赤ワインの信頼できる供給者として、そして一部のトップ生産者は冒険心のある消費者向けにプレミアムな複雑さの層を加えることに成功し、ブランドの再構築を果たした。しかしアラモンは、どちらの物語にも登場しなかった。

しかし2020年代に入ると、ワイン界はラングドックの赤ワインに背を向けるようになった。かつてはワインのアルコール度数が14%以上になることが頻繁にあることが、この産地の魅力的な差別化要因だったが、今では弱点と見なされている。ワイン愛好家は節度とバランスを求めており、ラングドックのグルナッシュ、シラー、メルロベースのブレンドではそれを提供できない。これを補うため、ブドウ栽培者は消費者が求めるものを提供しようと、ますます巧妙な脱アルコール技術に頼るようになっている。

そして2022年、私はベジエの北10マイルにあるマガラス村郊外のアローズ(Alauze)家のドメーヌ、ドメーヌ・ルー・ベルヴェスティ(Domaine Lou Belvestit)を訪れた。彼らが注いでくれたワインの中に、多くのロゼよりもわずかに濃い程度の色しかない赤ワインがあったが、それでも私の鼻にはガリーグの香りが、口にはベリー系果実の味わいが満ちた。100%純粋なアラモンだった。昼食が始まり、私の手は何度もこのボトルをグラスに注いでいた。爽やかな11%のアルコール度数だった。

当時その歴史を知らなかった私は、困惑して尋ねた。「なぜこれは他の場所で栽培されていないのですか?」

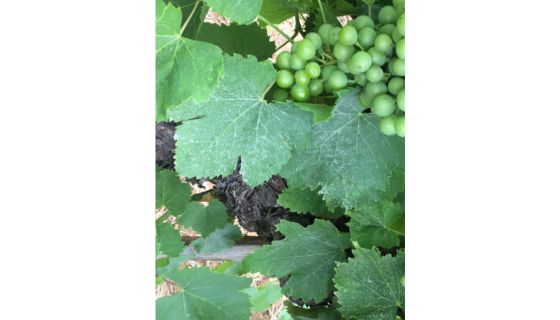

「アラモンの問題は」とアローズ氏は少し物悲しげに説明した。「何か面白いものを生み出すまでに80年かかることなのです。私の父が祖父をとても尊敬していたので、他の人たちが引き抜いた時にこれらの樹を残したのです」と言って、私にもう一杯注いでくれた。「そして80年後には...ご自分で味わってみてください」昼食後、彼のブドウ畑を見学した際、祖父が植えた節くれだったアラモンのゴブレ仕立ての樹を見せてくれた。まだ活発に生産しており、実際今が全盛期だった。それでもドメーヌ・ルー・ベルヴェスティのアラモンは、私が今まで味わった唯一のアラモンのままだ。

それ以来、私の心の目には、あり得たかもしれない世界が浮かんでいる。というのも、わずか10マイル先のピネ(Pinet)で、アラモンは白ワインの同等品を見つけているからだ。2000年、ピクプール(Picpoul)は地元の人だけが飲む無名でレモンのような沿岸の珍品に過ぎなかったのではないか?25年と勝利を収めたマーケティング・キャンペーンの後、ピクプール・ド・ピネ(Picpoul de Pinet)は遍在し、イギリスのほぼすべての中級レストランのリストで2番目に安い白ワインを提供している。ピクプールが真に偉大なワインを造るとは誰も主張していないが、それなりの地位を築いている。

ドメーヌ・ルー・ベルヴェスティで見つけるような品質の古いアラモンの樹がもっとあれば、アラモンのボトルは今ピクプール・ド・ピネを買っている同じ消費者の手に渡っているだろうと確信している。50年前にミディのブドウ栽培者がメルロ、カベルネ、シラーの収益性に誘惑されてアラモンを引き抜かなければ、彼らは今頃世界で最も人気のパーティー用赤ワインを提供し、それで十分な生計を立てていただろう。今日のワイン界は、自然で果実味があり、本質的にアルコール度数が低く、満足感を与えるが圧倒しない味わいを持つ赤ワインを求めて頭を悩ませている。そしてその答えは、マガラス郊外の斜面にある。しかし味わいが面白くなるまでに80年のリードタイムが必要なため、誰もすぐにアラモンを再び植えることはないだろう。

ある意味で、アラモンは確かに遺物だ。かつて支配的だった品種で、南フランスの一握りの風変わりな畑にしがみついている。しかし実際のところ、アラモンはそれ以上の何かだ。なぜなら古樹のアラモンを味わうことができれば、今日の飲み手はそれを大切にするだろうからだ。アラモンは決して実現しない次の大きなトレンドであり、ワイン界のジレンマに対する解決策は存在するが、何らかの違いを生み出すのに十分な量ではない。あり得たかもしれない未来だが、結局は決して実現することのない未来なのだ。

写真キャプション:「ローラン・アローズ(Roland Alauze)のアラモンのゴブレ仕立て」