Back in 2012, when Jancis, Julia and I published Wine Grapes, we’d written, ‘Kolorko is an almost extinct variety from the region between Uçmakdere and Şarköy in southern Trakya, along the northern coast of the Sea of Marmara, Türkiye. Since Kolorko does not appear in any official list, it is not yet known whether it is a unique variety or if it is a local name for another registered variety. This could be easily clarified by DNA profiling.’

A look back in time

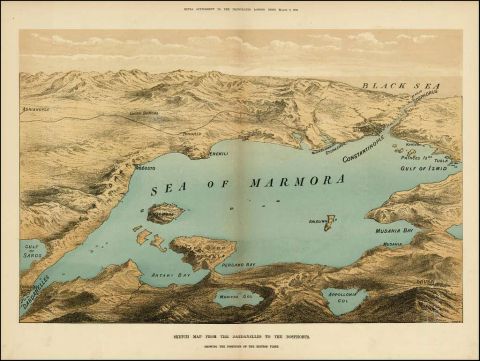

Declining since the 1960s, Kolorko was on the brink of extinction when Seyit Karagözoğlu, founder of Paşaeli Winery, began in 2005 to rescue it, collecting cuttings from the few old vines he could find still tended by growers in villages south of Tekirdağ (Uçmakdere, Şarköy, İğdebağları, Eriklice, Aşağıkalamış, Yukarıkalamış, Mürefte, Tepeköy, Çengelli, Çınarlı, Kirazlı, Mursallı, Hoşköy, Güzelköy, Gaziköy and others). Recognising the danger of losing the grape variety entirely, Karagözoğlu decided to re-establish it in Paşaeli’s Hoşköy vineyard, a site at 140–160 m (459–525 ft) in elevation, open to the wind off the nearby Sea of Marmara. In 2009, the first time they made a varietal version, they produced a meagre 276 bottles.

Julia Harding tried that 2009 the next year, enthusing in her tasting note over its herbal, citrusy aromas, mineral tones and rich texture, its depth and length. Several years later, after having tasted many more vintages, her tasting notes for the 2016 included the exhortation, ‘Keep going, Seyit!’ as she was so excited about the quality of this forgotten variety.

Meanwhile, I’d met Karagözoğlu in 2012, in Izmir at the Digital Wine Communication Conference, and was intrigued by all the wines he made from obscure indigenous Turkish varieties – especially the Kolorko, as almost nothing was known about its origin and history; there was no DNA profile made for it at that time. However, things were about to change.

The DNA test has spoken

In 2017, I was finally able to perform DNA profiling on some leaf samples of Kolorko that Karagözoğlu sent me. The result was mind-blowing: Kolorko’s DNA profile perfectly matched that of Furmint, the Hungarian grape responsible for the world-renowned wines of Tokaj in north-eastern Hungary.

I repeated the analysis using another, distinct sample in 2018. The result was exactly the same. There was no ambiguity: Kolorko and Furmint are one and the same grape variety. But how did Furmint end up in Thrace?

Furmint’s journey from Tokaj to Thrace

Karagözoğlu and I contacted István Szepsy Jr, one of Tokaj’s most respected producers, for help with exploring the historical context. The key to the mystery may lie with Francis II Rákóczi (1676–1735), leader of the Hungarian War of Independence against the Habsburgs.

After his defeat in 1708, Rákóczi fled to the Ottoman Empire, where he lived in exile in Tekirdağ (Rodostó in Hungarian), surrounded by a sizeable Hungarian entourage, including nobles and followers. He lived there for 18 years, over which time a large Hungarian community formed. While there’s no surviving document explicitly stating that vine cuttings were transported from Tokaj to Thrace, we can safely hypothesise that some Furmint vines were brought to the region from Tokaj at some point during this period.

Kolorko and Furmint, two biotypes?

Kolorko in Türkiye and Furmint in Tokaj share several features: they are both late ripening, with thick-skinned berries; they are both very susceptible to powdery mildew; they are both very high in catechin (an antioxidant phenol), and must therefore be pressed gently to avoid bitter flavours. Yet the wines made from each of them taste different.

One reason is the difference in terroirs. Between Şarköy and Tekirdağ, the climate is Mediterranean, influenced by the Sea of Marmara, and the soils are mainly calcareous and poor in nutrients. In Tokaj, the climate is continental and the soils are mostly volcanic.

The other reason is probably genetics. After several centuries of geographical separation, both Kolorko and Furmint have most likely accumulated somatic mutations, leading to environmental adaptation and resulting is small differences in shape, viticultural characteristics and flavour. A field trial should be set up, planting them side by side to see whether they are two biotypes (distinct forms within the same grape variety) or whether they are absolutely identical.

Kolorko today and tomorrow

Today at Paşaeli Winery, Kolorko is vinified as a dry white wine, fermented in stainless steel and aged briefly on its lees. Judging from Julia’s notes on nearly every vintage ever made, and mine as well, we can say that Kolorko wine is generally pale gold in colour, with a spicy, mineral and slightly stony aromatic profile, with notes of wax, honey and lemon oil. The palate is fresh and full-bodied, with flavours of bitter lemon, hints of pink grapefruit and a finish of pomelo. Vintage after vintage, this is a captivating wine.

Today, there are now two producers of Kolorko: Paşaeli and Melen winery. The discovery of Kolorko’s true identity could encourage other producers to follow in their footsteps.

A lost chapter of wine history found

For a grape geneticist, there is nothing more exciting than being able to understand genetic kinship through the prism of history. In this case, a single grape variety forms a living bridge between Hungary and Türkiye, linking Tokaj and Thrace across more than three centuries. Seyit Karagözoğlu, István Szepsy Jr and I are much looking forward to organising comparative tastings of Kolorko and Furmint!

The photo at the top of the article shows a bunch of Kolorko grapes at Paşaeli’s Hoşköy vineyard; taken by Seyit Karagözoğlu.

See our tasting note database for notes on 13 vintages of Kolorko from Paşaeli. You might also want to check out the 500+ we have for Furmint – most from Hungary, but also from Austria, Slovenia, Slovakia and more.