You may think me crazy but I would suggest buying fine Sauternes now.

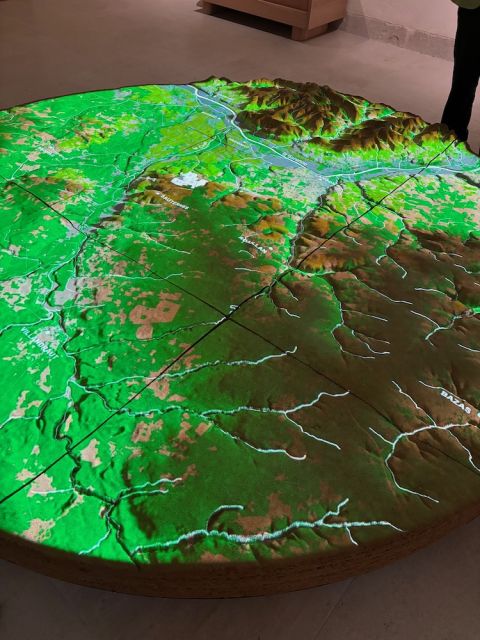

There’s absolutely no shortage of it and it is so unfashionable currently that prices are ridiculously modest in view of the difficulty of making it – far cheaper than equivalent red bordeaux. In my long career, I’ve seen so many reversals of trends that I feel Sauternes and its neighbour Barsac (shown in detail on this World Atlas of Wine map) are bound to find favour again. And because the best last almost forever, it doesn’t really matter how long this takes. Below I make some concrete suggestions for possible investments.

The one exception to this suggestion is the most highly regarded Sauternes of all, the property rated the finest in all Bordeaux in the famous 1855 classification, Château d’Yquem. Its wines are priced at almost 10 times as much as those of its neighbours so, while they’re outstanding and almost invariably thrilling (as this tasting article and the earlier one demonstrate), they cannot be considered underpriced (even if, thanks to the whims of fashion, they are very much less expensive than red Bordeaux first growths).

Yquem may feel justified in its marked premium over its classed-growth neighbours partly because it literally looks down on them all. Yquem is a grand, fortified, four-square building round a courtyard, on top of a hill from which you can see Châteaux Rieussec, Suduiraut, Sigalas Rabaud, Rabaud Promis, Lafaurie Peyraguey, de Rayne Vigneau, Guiraud and Clos Haut-Peyraguey. The view from the château is shown above. It’s also presumably because since 1999 it has been owned by LVMH, the luxury-goods company well-versed in commanding high prices.

From 1593 until then, Yquem had been in the same family, first the Sauvages and then, from 1785 when Joséphine de Sauvage d’Yquem married, the Lur-Saluces. The sale to LVMH was bitterly resisted initially by Comte Alexandre de Lur-Saluces, who had subsequently to content himself with his family’s less elevated Sauternes property, Château de Fargues.

During my visit to Château d'Yquem in May 2025 with fellow 1950 Babes, I couldn't help noticing that the initials above the main door had been changed from LS for Lur-Saluces to BA for Bernard Arnault, boss of LVMH.

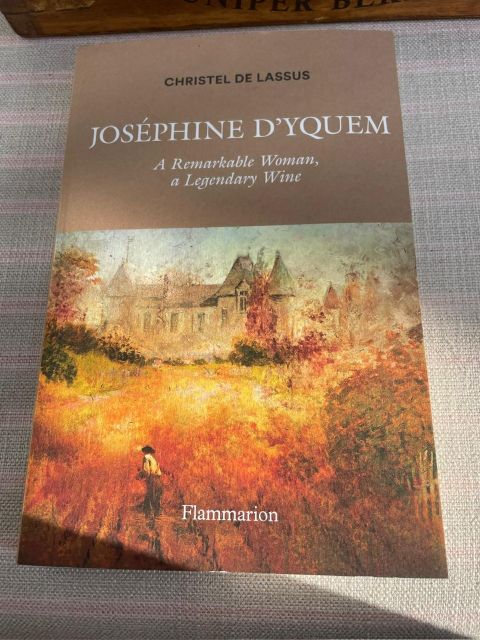

An English edition of a 2023 biography of Joséphine has just been published by Flammarion and very fascinating it is too. It outlines how, many years before the other young widows Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin and Dona Antónia Ferreira would do the same for champagne and port respectively, Joséphine fought to make her wine the very best it could be and introduced real innovation in making and selling Sauternes.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, when she was in her early thirties, she identified the key ingredient in making top-quality sweet white bordeaux, a strange mould called Botrytis cinerea, noble rot colloquially. She noticed that the best wines were made from fully ripe grapes that, apparently randomly, had shrivelled on the vine and were covered in a rather disgusting-looking sort of purplish-grey dust. (The picture below was not taken at Yquem.)

This special fungus magically concentrates the sugars in pale-skinned grapes and does much more besides; the acidity is concentrated in the shrivelled berries. Joséphine and her steward Jean Garros would not have known the complex chemical and physical reactions within the grape triggered by an attack of noble rot, but they realised that they would make even better wine if they sent pickers through the vineyard multiple times to pick only the affected bunches, or even individual grapes, each time. Joséphine died in 1851 so did not live to see the great honour bestowed on her beloved Yquem four years later but the determination to pick selectively undoubtedly played its part.

This still happens today and is now standard practice in such Sauternes properties as can afford it, although few can financially justify such fastidiousness and as many passes through the vineyard as Château d’Yquem. For their 106 ha (262 acres) of Sémillon (70%) and Sauvignon Blanc (30%) vines in production they need up to 140 seasonal local pickers to be on call for as many as seven different passages through the vineyard. The harvest now starts in August and can extend into November. In 1985 the last grapes were picked on 19 December.

The pickers have to be available seven days a week and are paid only for the days on which they pick, when they get breakfast and lunch. They may have to work on a Sunday, when, according to the 36-year-old estate manager, recently promoted to CEO, Lorenzo Pasquini, pictured above having just decided on the blend for Yquem 2024, they get choux à la crème.

This is highly specialised work for which careful training is needed. Last May Pasquini told me the average age of the pickers is 60, that more than one-third of them are over 70 and more than half are women. He’s trying to recruit about 10% new pickers each year but it can’t be easy, even though each picker is given a bottle of Yquem, and handsome quarters for their vintage party is part of the extensive building work currently underway at Yquem.

Pasquini is in charge of a major revitalisation programme. Much of the new building is devoted to welcoming visitors. The first thing you encounter on Yquem’s smart website is an invitation to choose a formula for a visit, from €70 per person for nothing more than a taste in the glamorous tasting room, part of which is shown above, up to €300 for a private visit followed by a taste of the 2015, 2010 and 2005 vintages. The size of the pours is not specified but, I was assured, the 2005 is especially famous for being the result of five different generations of botrytis.

There’s a hi-tech presentation of the renovated estate and all sorts of refinements to the recipe, which, according to Pasquini, a young Italian who has arrived at what seems like the job of his dreams via making wine in California and Argentina, ‘is the most minimal in the world’ since all the selection has been done in the field. They have been reducing the time spent in barrel from three to two years and working on the aromatic potential. From the record hot, dry 2022 growing season, soon after Pasquini’s arrival, they have reduced the wine’s exposure to oxygen during that barrel ageing, and tried to compensate for the low acidity with light bitterness.

As with many of the wine estates directed by the Arnaults of LVMH, there’s a particular emphasis on sustainability, with the aim of being carbon-neutral by 2035.

Celebrated chef Olivier Brulard has been on the books at the château since 2019 and his focus is on showing how, as Comte Alexandre Lur-Saluces demonstrated to me and Nick over lunch back in the 1980s, Yquem can be enjoyed throughout a meal, even with savoury foods. Pasquini also points out that, although half bottles of Sauternes are in demand, the wine keeps well in an opened bottle so he would like to see more people splashing out on whole bottles.

The Yquem team take pairing food with their produce very seriously. Canapés with our Yquem 2022 while we enjoyed our pre-lunch aperitif included Kobe beef and caviar, jamón ibérico and juicy melon, melt-in-the-mouth foie gras, and squid with orange. How we suffered ...

In the great wide world outside Bordeaux a programme was instituted in 2022 to encourage selected restaurants, wine bars and clubs to serve Yquem by the glass. (A similar programme boosted the appreciation of the Napa Valley Cabernet Opus One back in the 1990s.) I’d dearly love to see more wine drinkers enjoy the special qualities of truly fine sweet wine, but to judge from what’s available on the market, an ever-higher proportion of grapes grown in the Sauternes region are made into dry wines.

Most châteaux there, depressed by the lack of demand for their sweet wines and mindful of the cost of producing them, are developing dry wines from their Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon grapes. Some of them are even lobbying for a special Sauternes Sec appellation for them. Early versions used to be a bit heavy and unappetising but the quality has been improving.

Yquem’s dry version, called Ygrec after the French for the letter Y, was launched in 1959, which rather shocked the Sauternais at the time. Initially it was really, really heavy, made from grapes picked at the end of the harvest and with a suggestion of botrytis – truly a sort of dryish Sauternes. Today it’s made from grapes picked in August before they reach full ripeness. Since 2001 they have increased the proportion of Sémillon again so that it was 40% in the very lively 2022.

Pasquini is convinced that 2022 comes in the middle of an exceptional trio of vintages, 2021, 2022 and 2023, as good as 1988, 1989 and 1990 – and even 1948, 1949 and 1950. Might this most recent trio serve to change a few minds?

Fine Sauternes worth a punt

I scored all of these at least 18.5 out of 20. Most are quite widely available in the US and, especially, Hong Kong. Certain wines feature often because they have been bundled with more sought-after associated red wines. Most are 13.5 or 14% alcohol.

Halves

Ch Doisy-Daëne 2007

£21.30 per half Four Walls Wine Company

Ch Rieussec 2010

£27.90 per half Friarwood Wines & Spirits

Ch Coutet 2001

£30 per half Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Suduiraut 2011

£35 per half The Perfect Bottle

Ch Climens 2015

£35 per half Wine Trove

Ch La Tour Blanche 2010

£35 per half Hedonism

Ch Suduiraut 2009

£35.94 per half Four Walls Wine Company

Ch Climens 2006

£36 per half Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Climens 2009

£42 per half Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Climens 2003

£42 per half Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Climens 2010

£44 per half Berry Bros & Rudd

Ch Climens 2005

£50 per half Hedonism

Ch Rieussec 2001

£50.40 per half Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Climens 2001

£65.83 per half in bond Wilkinson Vintners

Bottles

Ch de Rayne Vigneau 2016

£32.75 Premium Grands Crus

Ch Raymond-Lafon 2015

£38.40 Four Walls Wine Company

Ch Rieussec 2007

£48.08 Vinatis

Ch Suduiraut 2010

£55 Hedonism

Ch Rieussec 2009

£55 Wine Trove

Ch Suduiraut 2005

£56.70 Four Walls Wine Company

Ch Coutet 2007

£61.90 Millesima UK

Ch La Tour Blanche 2009

£72 Ancient & Modern Wines

Ch Climens 2004

£79 Cru World Wine

Ch de Fargues 2009

£79.14 Four Walls Wine Company

Ch Suduiraut 2017

£79.40 Millesima UK

Ch Rieussec 2001

£84 Cru World Wine

Ch de Fargues 2011

£118 Cru World Wine

Cases (all in bond)

Ch Raymond-Lafon 2009

£250 per dozen Goedhuis Waddesdon

Clos Haut-Peyraguey 2007

£280 per dozen Farr Vintners

Ch La Tour Blanche 2005

£325 per dozen Grand Vin Wine Merchants, £354 per 24 halves Bordeaux Index

Ch Doisy-Daëne 2015

£188 per six Fine+Rare

Ch de Rayne Vigneau 2016

£190 per six Ideal Wine Company

Ch Climens 2011

£199 per 12 halves BBX

Ch Suduiraut 2001

£507.50 per six Cru World Wine

See our summary vintage assessments, and see our database for tasting notes, scores and suggested drinking dates. For international stockists, see Wine-Searcher.com.

Back to basics

| Sweetness in wine |

|

Many a supposedly dry wine has quite a bit of sugar in it, reds as well as whites. The website of the Québec liquor monopoly, saq.com, is wonderfully useful in giving residual sugar levels of the wines it sells. Anything below 2 g/l is generally accepted as being imperceptible but Yellow Tail Australian Shiraz, for example, is 10 g/l. Gallo White Zinfandel is 39 g/l, while most commercial New Zealand Sauvignon Blancs are around 4 g/l.

Acidity is the counterbalance to sweetness; the tarter the wine, the less obvious any sweetness will be. So the sweetness level in champagnes other than Extra Brut and Brut Nature or Brut Zéro tends to be a little higher than in the average still wine.

Sweetness in wine can be the result of botrytis, or because the grapes have simply raisined on the vine, or have been dried after picking to increase the sugar level, or have frozen on the vine and are pressed to make sweet Icewine, or the winemaker has deliberately halted fermentation before all the grape sugar has been fermented into alcohol, or has added sweet, concentrated grape juice. |

| See The Oxford Companion to Wine entries on sweet winemaking and sweet wines. |