この記事は、できるだけ早くお届けするためにまずAIで翻訳したものです。今後はAIに教育を行うことでその精度を上げること、それと並行し翻訳者が日本語監修を行った記事と、AI翻訳のみによる和訳記事を明確に分けることで、読者の皆様の利便性を最大限に高めることを目指しています。表現に一部不自然な箇所がある場合があります。ご了承ください。

プーン(Poon)という姓は、ホスピタリティと中華料理の世界で長い間親しまれてきた。

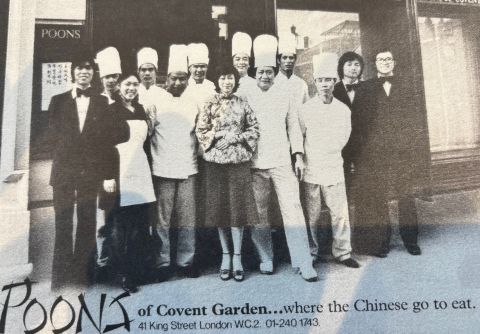

ビル・プーン(Bill Poon)が青年時代に働き始めたマカオのレストランから、1980年にロンドンのコヴェント・ガーデンでミシュランの星を獲得したレストラン、そしてさらに2軒のレストラン(そのうち1軒はジュネーブ)まで。しかし2004年、ビル・プーンは包丁を置き、セシリア(Cecilia)は温かい笑顔での接客を引退した。2人とも現在80代で、ロンドン南東部のサリー・キーズ(Surrey Quays)で幸せに暮らしている。

その重責は娘のエイミー(Amy)の肩にかかった。2018年にロンドンに戻って以来、彼女はロンドンのレストラン業界に時には本格的に関わってきた。カルーセル(Carousel)での3か月間のポップアップ、ワンタンと美味しくパッケージされたソース類(特にスパイシーなチリビネガー)の販売(現在も販売中)、そして潜在的な大家との実らない交渉を何度も重ねてきた。

そして今年11月5日、プーンズ・ロンドン(Poon's London)がサマセット・ハウスの常設店舗として扉を再び開いた。場所は故スカイ・ギンゲル(Skye Gyngell)のレストラン、スプリング(Spring)の隣だ。初回のランチの後にエイミーと会う約束をした際の私の最初の質問は、「これは掻かずにはいられない痒みのようなものですか?」だった。彼女は微笑み、数秒考えてから答えた。「運命、私の宿命だと思っています」

その宿命には長時間労働が伴う。いつ話をしに来られるかと尋ねた時、彼女の答えは「いつでも、私たちはここに住んでいるようなものですから」だった。私が一人でランチを取っていた時のことだ。たっぷりのチキンが入った温かいお粥を食べながら夫のマイケル(Michael)と話していると、彼女がテーブル越しに身を乗り出し、4切れの漬物が入った小さなボウルを覗き込み、私たち2人を見上げて微笑んでから「チェックしているだけです」と付け加えた。

これは、レストランの2つのエリアのうち最初のエリアを占めるカウンター席でのランチだった。向かい側にはテーブル席があり、2つ目のエリアにもテーブル席がある。そして真正面にはオープンキッチンとバー席がある。店内全体はアーティストのレオノラ・サービス(Leonora Service)が描いた壁画で覆われ、緑豊かな中国の雰囲気を演出している。家具も緑が基調色だ。店の奥のマントルピースには年老いたビル・プーンの写真が置かれ、まるで皆と全てを見守っているかのようだ。

エイミー・プーンの使命は当然ながら不可能に近い。家庭料理とスタイルを組み合わせた温かい雰囲気の創造を目指している。称賛すべき野心だが、常に彼女の夢であり続けるだろう。しかし彼女は、扱いにくい環境から素晴らしい空間を作り出すことに成功した。レストランは18世紀の建物の東側に沿った細長いスペースを占めている。この建物は元々政府庁舎として使われ、徐々にレストランが併設された芸術センターに変貌した。レストランへは東側から、ウォータールー橋の延長線上からアクセスするのが最も簡単だ。

この立地には特有の課題がある。廊下がレストランと食器洗い場、そして写真上のプライベート・ダイニング・ルームを分けている。レストランには専用のトイレがなく、廊下沿いの共用トイレを使用する。建物全体で火気の使用が禁止されているため、中華鍋での調理は最高出力のIHコンロで行わなければならない。そしてもちろん、現状維持が最善だと信じる大家と、簡単に改善できると信じるテナントの間で、看板の問題は常に課題となっている。

野菜の仕入れ業者、キノコの仕入れ業者、そしてシェフのマーティン・ラム(Martin Lam)と4人用テーブルでランチを取った際、私たちはメニューをより詳しく探求した。まず、ローストダック・サラダの小皿、茹でピーナッツ、名物の風乾ソーセージのスライスが入ったボウル、そして豚の背脂を衣に使ったビル・プーン流のエビトーストから始めた。その後、ネギと生姜の蒸し鱸、発酵大豆ソースを加えた炸醤(zha jiang)ナス、豆腐とキノコの煮込み春雨、季節の青菜、そして土鍋で炊いたジャスミン・ライスへと進んだ。美味しいドイツのリースリング(Riesling)と共に、私の会計は230.40ポンドだった。

私たちの料理全てに欠けていたもの、そして時間だけが解決できるものは、使い込まれた鍋や中華鍋での調理がもたらす根底にある豊かさと追加の層だ。どのレストランも忙しくなるにつれて、厨房機器は叩かれ、打たれ、使い込まれ、バター、調理油、そしてプーンズの場合は特に、スパイス、酢、中華レストラン料理の特徴である甘さとスパイスの独特な混合物の薄い層で覆われる。どのレストランでも最初の6か月で多くのことが変わるが、厨房にほぼ無意識に染み付くこれらの追加の風味ほど変化するものはない。これら全てが、プーンズの料理をさらに魅力的にするだろう。

改善はできないが進化するのは、エイミーの夫マイケル・マッケンジー(Michael Mackenzie)がワインリストを作成する際に取った思慮深いアプローチだ。妻が「博士論文を書いている」と表現したように。「私たちがワインで愛するもの」という見出しの下で、彼は伝統と情熱を持つ家族経営や女性生産者による冷涼気候のワインという指針を示している。また、リストのワインは全て100ポンド以下だと指摘している。彼は以前ワイン業界にいて、アジアでシャンパーニュを販売していた(シャンパーニュが2人を結びつけた)。ここで彼は3種類のシェリーをリストアップし、香港生まれでシェフからワインメーカーに転身してリオハ・アルタで働くジェイド・グロス(Jade Gross)のワインを多く選んだ理由を説明し、私たちに提供したマキシミン・グリュンホイザー、ヘレンベルク・リースリング・カビネット2023(68ポンド)を大いに楽しんだ。アルコール度数7.5%は、ランチに完璧なワインだった。

食事の最後は「ヘレン・ゴー(Helen Goh)の3口」と表現されたデザートで締めくくった。マレーシア生まれの心理学者で、ロンドンに移住後、ヨタム・オットレンギ(Yotam Ottolenghi)と共にペストリー・シェフとして活躍している人物だ。ゴーとの会話で、プーンは伝統的な中華料理にデザートがないことを嘆いていた。特にフランスの影響が強いベトナム料理と比較してのことだった。手始めとして、ゴーが提案したのが私たちが楽しんだ料理だった。季節のフルーツ1切れ(私たちの場合は柿)、チョコレート1片、スポンジケーキ1片。どれも美味しかったが、時間と共に新鮮なアイデアが生まれるだろう。

私にとって、このレストランのオープンで最もエキサイティングなのはそこだ。オーナーたちは、この業界のほとんどの人々を駆り立てる金銭的な動機に駆られていない。エイミー・プーンは父親の料理の雰囲気と香りを再現するという使命を帯びており、多くの人がこの家庭的な料理スタイルをレストランで再現しようと試みてきた。定義上、彼らは皆ほぼ失敗している。

しかし、エイミー・プーンのような決意、責任感、歴史感を持つ人に対して、私は決して賭けに負けることはないだろう。そして彼女が厨房で働く人々、特にウズベキスタン人シェフのシャフカット・マムロフ(Shavkat Mamurov)と香港生まれのスー・シェフ、ジョイエタ・ン(Joyeta Ng)にインスピレーションを与え続ける中で、このメニューは進化し、さらに良くなるだろう。プーンズというレストラン名が中国や世界中から訪問者を引きつける方法によって、彼女は間違いなく大いに助けられるだろう。

プーンズ・アット・サマセット・ハウス(Poon's at Somerset House) New Wing, Lancaster Place, London WC2R 1LA; tel: +44 (0)20 7759 1888. 日曜・月曜定休。

毎週日曜日、ニック(Nick)はレストランについて書いている。彼のレビューを追いかけるには、私たちの週刊ニュースレターにサインアップを。